Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

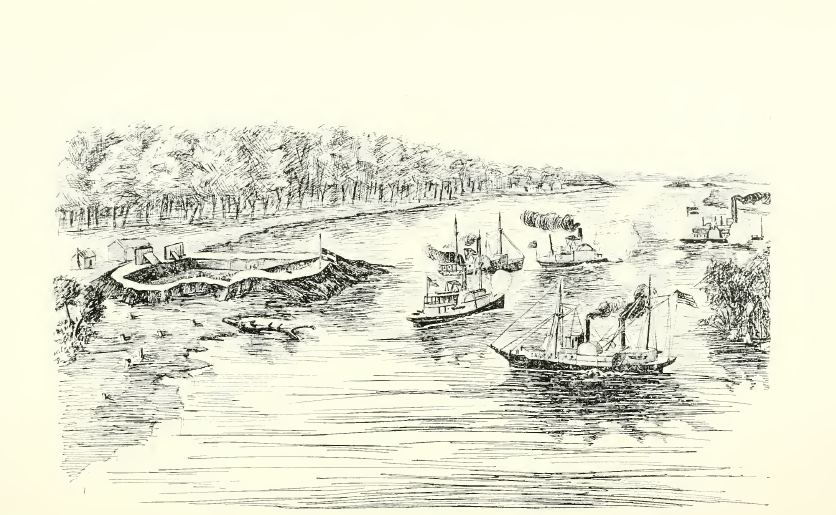

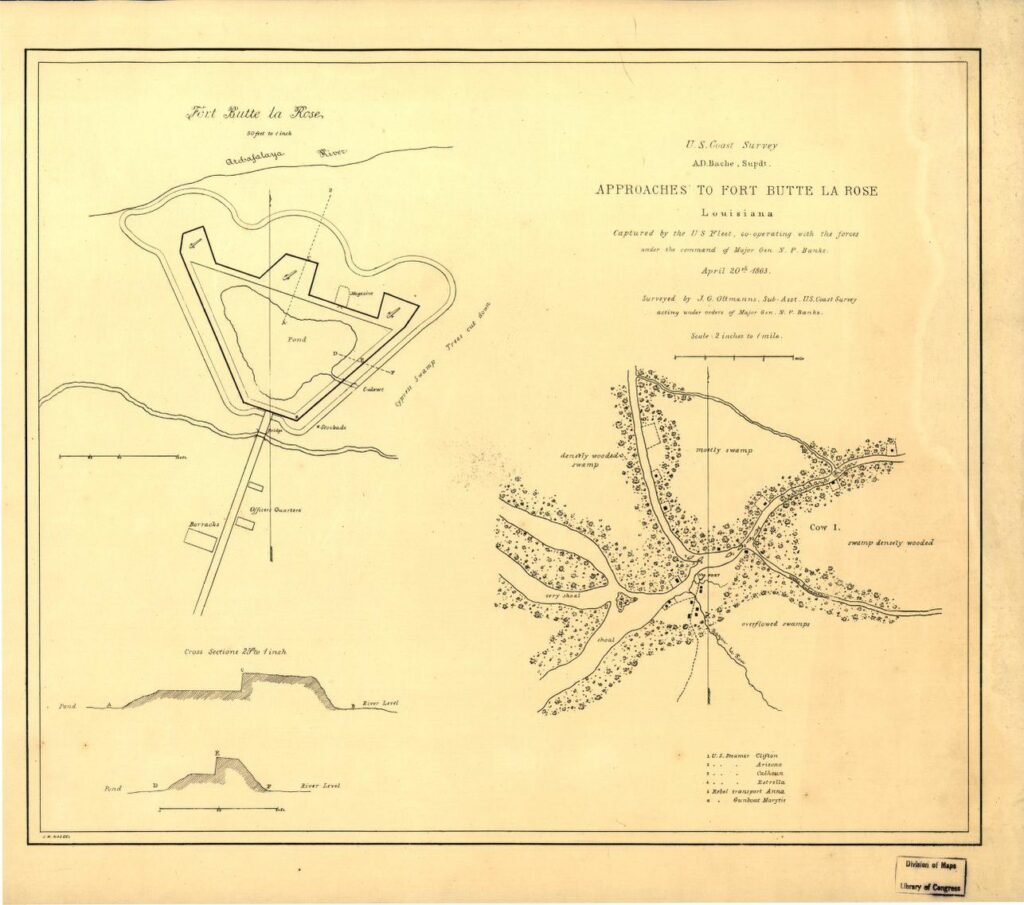

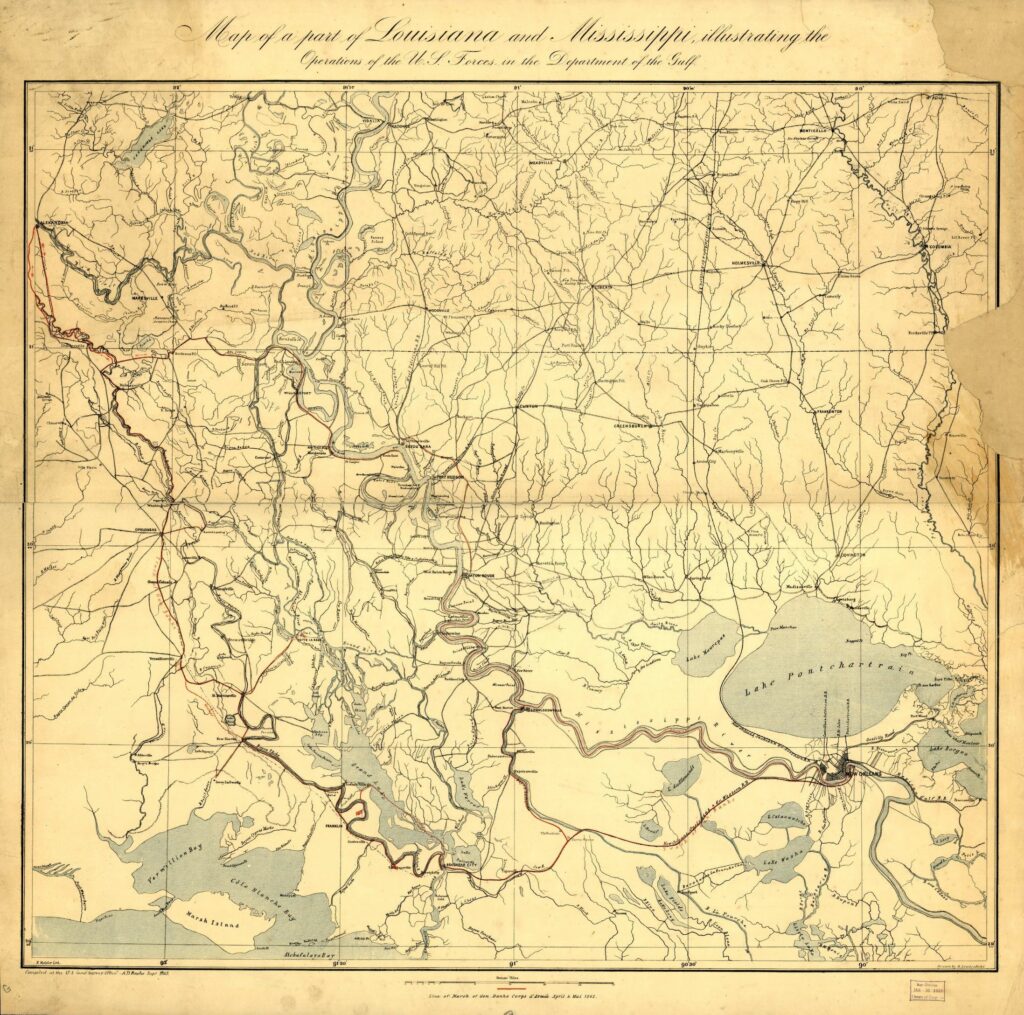

On the afternoon of April 18, 1863, soldiers from the 16th New Hampshire Infantry boarded four gunboats at Brashear City (modern Morgan City), Louisiana, and set a course up the wide Grand Lake. Their destination was Fort Burton: a small Confederate work atop a bluff, known as Butte à la Rose, on the Atchafalaya River. Taking this fort would open up the Atchafalaya to Union forces, a move that Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks viewed as crucial to his ongoing operations in the sugar and cotton-rich Bayou Teche region to the west. When the small flotilla arrived off Butte à la Rose two days later, the sixty Confederate defenders decided their wisest course of action was to surrender without a fight. One of the new prisoners informed the 16th New Hampshire’s Lieutenant Colonel Henry W. Fuller that he was actually “damned glad” to be captured. “They had staid there in the swamps as long as they desired to,” Fuller said, “and they thought when we had been there a few months we would be glad to surrender also.”[1] Little did the Northern regiment know how true this would be.

Sickness and death plagued the 16th New Hampshire at Fort Burton over the next six weeks, and by the time of their return home at the expiration of their nine-month enlistments in August, disease had claimed the lives of one-quarter of the Union men. Many Civil War regiments suffered grievous casualties in battle. But for the 16th New Hampshire, who saw little action and did not lose a man to Confederate bullets, the invisible enemy of disease defined their service in the Civil War.[2]

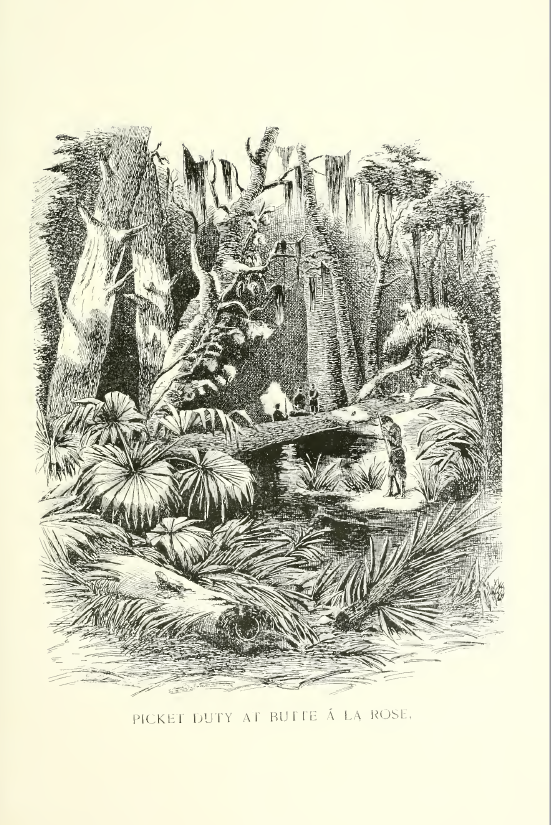

The name Butte à la Rose – which means “bank of the rose” – belied the true conditions at Fort Burton. The bayous of Louisiana surrounded the work on all sides, and an “undisguised swamp” made up much of the fort’s interior. The landscape surrounding Fort Burton was unlike anything these New Hampshire soldiers had seen before. “It was the grand rendezvous,” the regimental historian recalled many years later, “of mosquitoes, fleas, wood-ticks, lice, lizards, frogs, snakes, alligators, fever bacteria, dysentery microbes, and every conceivable type of malarial poison.” The men heard alligators splashing in the water uncomfortably close to their camp during the night, watched small lizards scamper across the floors of their tents, and sometimes had to shoot water moccasins out of pathways between the barracks.[3]

Disease-carrying mosquitoes were the regiment’s biggest threat. Private George C. Andrews, a teenager from the town of New Boston, complained in his diary on April 28 that the “mosquetow and flies liked to eat us” when on picket duty. Another soldier had a slightly different take on these pests. “These little rascals are comparatively civil and respectful during the day,” he wrote home to a local newspaper, “but at the approach of night their scattered forces are heard…and can be seen ‘massing’ their columns in the immediate vicinity of their intended point of attack, and piping up their accursed strains as a kind of prelude to combined assaults upon those whose blood they seek.”[4]

In these conditions, the health of the men of the regiment, many of whom were weakened by disease before arriving at Fort Burton, rapidly declined. By May 1, Private Andrews already reported that the “warm weather [had] taken hold of the soldiers.” Men became sick and died almost daily; funerals were a regular occurrence, and pine-board tombstones, inscribed with lead pencil markings, soon dotted the marshy landscape around Butte à la Rose. The regiment tried to keep up morale by maintaining a rigorous schedule of picket duty, dress parades, and drill, but the situation seemed hopeless. The men felt as if they had been left in the Louisiana swamps to die. “How long we’re to stay in this place nobody knows,” Andrew Farnum of Company D wrote his father in West Concord, “but I hope not long.”[5]

The river dropped as summer approached, exposing stinking mudflats that added to the men’s misery. The regiment worried that the low water levels would prevent any resupply or rescue by boat from Brashear City. Finally, on May 29 a month and a half after their arrival, a gunboat and two transports arrived at Butte à la Rose to evacuate the 16th New Hampshire. Out of the nearly six-hundred men who had originally embarked upon the expedition, barely one-hundred were able to leave Fort Burton under their own power. A Massachusetts officer who accompanied the rescue force sadly recalled the “long procession of men carrying the sick on stretchers and spreading them out over the decks of the boats,” and looking down from his perch in the pilot house to see the “solid piles of motionless, blanketed men stretched out straight on their backs, quiet as the dead that they so closely resembled.”[6]

After leaving Fort Burton, the survivors joined the rest of Banks’ army in the siege of Port Hudson. They rarely experienced anything heavier than skirmish fire, but death continued to stalk the 16th New Hampshire. Private Andrews himself lost a close friend from his company in early June. “I was affraid that he could not live the last time I saw him,” Andrews wrote his father, “but it come pretty tough to me when I heard that he was dead.” Andrews’ pain was hardly unique in his regiment. When the regiment mustered out in Concord in August, disease had taken the lives of 210 men out of the original 914 who left the state the year before. This twenty-three percent fatality rate was comparable only to regiments from the state who served multiple years – not mere months – and that suffered extensive combat deaths as well.[7]

But the dying did not cease with the dissolution of the regiment. Nearly one-hundred more were gone by the end of the year. Among them was young Private Andrews, who died on September 6. His family buried him in the town cemetery, and placed the epitaph “Soldier, rest: thy warfare is over” on his tombstone.[8]

The postscript of the regimental history, written by former Adjutant Luther Tracy Townsend, provides a glimpse into the regiment’s struggle to define their service and sacrifices. “Throughout the campaign,” Townsend wrote, “if the losses we had suffered by disease had been incurred on the field, our record certainly would have seemed more heroic.” He went on to pose a question to the reader: “But are gunshot wounds worse than those diseases that brought to hundreds of our men certain and often sudden death?” Sadly, the 16th New Hampshire’s brief, but tragic, service has been overshadowed by regiments from the state that left their dead on the battlefield. The survivors of the regiment were left to reconcile the fact that death in war was only heroic if it came in the throes of battle. Dying in a feverous delirium in the swamps won them no glory.[9]

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Nathan A. Marzoli is a staff historian at the Air National Guard History Office, located on Joint Base Andrews. A U.S. Air Force veteran, he completed his bachelor’s degree in history and master’s degree in history and museum studies at the University of New Hampshire. Marzoli’s primary researching and writing interests focus on conscription in the Civil War North. He is the author of several articles, including “‘A Region Which Will at the Same Time Delight and Disgust You:’ Landscape Transformation and Changing Environmental Relationships in Civil War Washington, D.C.” (Civil War History); “‘We Are Seeing Something of Real War Now:’ The 3d, 4th and 7th New Hampshire on Morris Island, July–September 1863” (Winner of the 2017 Army Historical Foundation’s Distinguished Writing Award); “‘Their Loss Was Necessarily Severe:’ The 12th New Hampshire at Chancellorsville”; and “‘The Best Substitute:’ U.S. Army Low-Mountain Training in the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains, 1943–1944″ (Army History).

Endnotes

[1] James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 637; Jeffrey S. Prushankin, The U.S. Army Campaigns of the Civil War: The Civil War in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, 1861-1865 (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 2015), 34-35; U.S. Government, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Volume 15 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1886), 299, 873; Mike Pride, Our War: Days and Events in the Fight for the Union (Concord, NH: Monitor Publishing, 2012), 179.

[2] Augustus D. Ayling, Revised Register of the Soldiers and Sailors of New Hampshire in the War of the Rebellion 1861-1866 (Concord, NH: Ira C. Evans, Public Printer, 1895), 790.

[3] Luther Tracy Townsend, History of the Sixteenth Regiment, New Hampshire Volunteers (Washington, D.C.: Norman T. Elliott, Printer and Publisher, 1897), 189-93, 207.

[4] Townsend, Sixteenth N.H., 189-190; George C. Andrews diary, April 28, 1863, Milne Special Collections and Archives, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, NH.

[5] Townsend, Sixteenth N.H., 195-202; Andrews diary, May 1, 1863, UNHL; Pride, Our War, 181.

[6] Townsend, Sixteenth N.H., 196, 202, 205-208, 210.

[7] Aylings, Revised Register, 790.

[8] Mike Pride, “Private Andrews’ Long Road Home,” February 27, 2014, https://ourwarmikepride.blogspot.com/2014/02/private-andrewss-long-road-home.html

[9] Townsend, Sixteenth N.H., 293.