Table of Contents

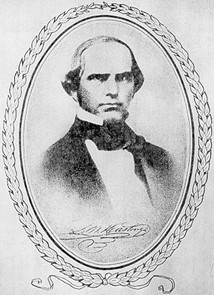

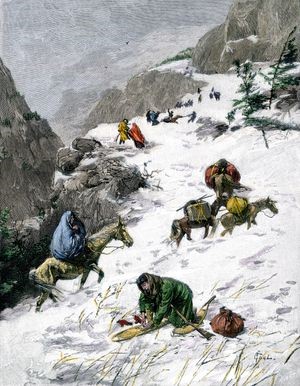

Lansford Hastings is irrevocably tied to the Donner Party tragedy-an 1846 wagon train party that became stuck in the Sierra Nevada and resorted to cannibalism in order to survive. This is due to his promotion of the “Hastings Cutoff”- an alternative route on the Oregon Trail that Hastings assured would save the immigrants 300 miles and deliver them to the West Coast a month earlier than the traditional route.[1] He has historically been portrayed as an ambitious and unscrupulous individual who, eager for acclaim and political power, encouraged naïve pioneers to cross a treacherous landscape that resulted in their starvation and death. While many know Hastings due to his connection with the Donner Party, he also played a small part in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, and the subsequent Confederado settlements in Brazil after the war ended.

During the Civil War, Hastings was living with his family in Yuma, Arizona- a territory he planned to take over from the Union.[2] His plan was promising enough that in 1863, he secured a meeting with President Jefferson Davis to discuss it. Hastings’ initial plan was to “retake and permanently hold the Territory of Arizona.”[3] The forces were to be drawn by raising three to five thousand troops in California who would then be taken to Arizona disguised “as miners and emigrants to Mexico.”[4] Hastings would then “reduce the U.S. forts and capture the troops,” eventually taking hold of the federal property in the territory in the name of the Confederacy. Additionally, he would establish a Confederate Territorial Government there, which would enable communication to be kept open between the Pacific and Texas. This “unbroken intercourse between California and the Confederate states” would thus “enable the thousands of Californians who desire to aid in the Confederate cause to do so at will and with safety.”[5] Unfortunately, Hastings was informed by the Confederate Secretary of War that the government could not partake in his endeavor due to a lack of funds. Hastings subsequently downscaled his strategy, but his revised plan appears to be even more convoluted.

In his new plan, Hastings proposed to return to California via Mexico where he would charter vessels and recruit soldiers as “miners” in the names of various mining companies. He would also transport “emigrants” using the name of the Mexican Immigration Aid Society.[6] These disguised troops would be sent to Guaymas and “the mines in the vicinity of Yuma.”[7] From there, a secret agent would travel from the Confederacy to Guaymas with the needed funds and feign to be the agent of various mining companies and the Immigrant Aid Society. Once a sufficient number of troops had reached Arizona and Colorado, Hastings would meet them, all the while continuing to send more troops until “the news shall have reached California that the Confederate flag floats in Arizona.”[8] Hastings and his men would capture Fort Yuma, successfully “demolishing” the Union’s “key and only means of transportation to that Territory.”[9] He would try and recruit the Union prisoners of war from Fort Yuma and use the confiscated trains to move all valuables to the interior of Colorado. From here, Hastings would allow the secret agent in charge of sending men from Mexico to use his best judgment. If he felt he had enough forces, the agent could “surprise and capture Fort Buchanan at once” while preventing any Federal civil officers from escaping.[10] If he did not have enough support, the agent was advised to “remain with his men in the character of miners and immigrants within the Mexican territory” until Hastings and his troops from Colorado could reunite with them.[11] Assuming it was to be a success, Hastings wanted to repeat this strategy for New Mexico. Hastings was denied once again and made no further attempts to put his ideas into action.

After the war ended, Hastings was one of 20,000 Confederates who moved to the slaveholding country of Brazil rather than reintegrate with the Union. They established colonies and referred to themselves as “Confederados.”[12] Both Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee encouraged the South to stay and rebuild, but many like Hastings felt that to stay would be akin to living under a hostile foreign occupation. Brazil was particularly attractive to Confederates because of its ruler Dom Pedro II who had aided them during the war.[13] Afterwards, Pedro advertised in the newspapers of the defeated South, offering “subsidized transportation to Brazil and land available for as little as 22 cents per acre.”[14] Brazil was portrayed as a pro-slavery country where the Confederates could settle and live as they had before the war. Hastings helped to spread the word of this new opportunity by publishing The Emigrant’s Guide to Brazil in 1867. The guide promised “unlimited wealth” and a revival of the plantation system. Unfortunately for Hastings, he died while leading a second voyage of ex-Confederates to Brazil.[15] The Confederado colonies ultimately failed in resurrecting the slave system, and many returned to the U.S. following Jim Crow. This was the second and last time Hastings would lead others on a futile adventure ridden with empty promises.

About the Author

Elizabeth Eisenstark is the research and collections assistant at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. She received a BA in the History of Art and Visual Culture from the University of California Santa Cruz and is currently pursuing a post-bacc in Anthropology with a focus on Archaeology from Oregon State University.

Sources

[1] Kiniry, Laura. “The Deadly Temptation of the Oregon Trail Shortcut.” Atlas Obscura, Atlas Obscura, 12 May 2021, www.atlasobscura.com/articles/oregon-trail-shortcuts.

[2] Hunsaker, William J. “Lansford W. Hastings’ Project for the Invasion and Conquest of Arizona and New Mexico for the Southern Confederacy.” Arizona Historical Review, Volume 4 (1931-1932), repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/617819. Accessed 15 Dec. 2023.

[3] Ibid., 8.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 9.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., 11.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Dunn, Morgan. “When the South Lost the Civil War, 20,000 Confederates Fled to Brazil to Build a Slave Kingdom.” All That’s Interesting, All That’s Interesting, 17 Oct. 2022, allthatsinteresting.com/confederados.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Hunsaker, William J. “Lansford W. Hastings’ Project for the Invasion and Conquest of Arizona and New Mexico for the Southern Confederacy.” Arizona Historical Review, Volume 4 (1931-1932), repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/617819. Accessed 15 Dec. 2023.