Table of Contents

Museum members are the reason we can bring you scholarship like this.

CONSIDER SUPPORTING THE MUSEUM TODAY

Nicholas Wee panicked when his name was drawn in the Federal draft. He desperately wanted to avoid service in the Union army, so Wee decided to try and trick his examining surgeon into believing he was unfit for military service. Somehow the draftee’s best idea was to soak his feet in hot, caustic lye over a period of ten days, making his feet painfully raw and irritated when he hobbled into his medical exam. The surgeon for Minnesota’s Second District, J.H. Stewart, was not fooled; he had seen hundreds of attempts like this before. “As the best means of unfolding the fraud,” Stewart reported, “the man was dismissed with a certificate of exemption.” Wee probably thought he had beaten the system, but Stewart tracked him down and had him arrested sixty days later. The draftee’s feet were magically healed, confirming the doctor’s suspicions.

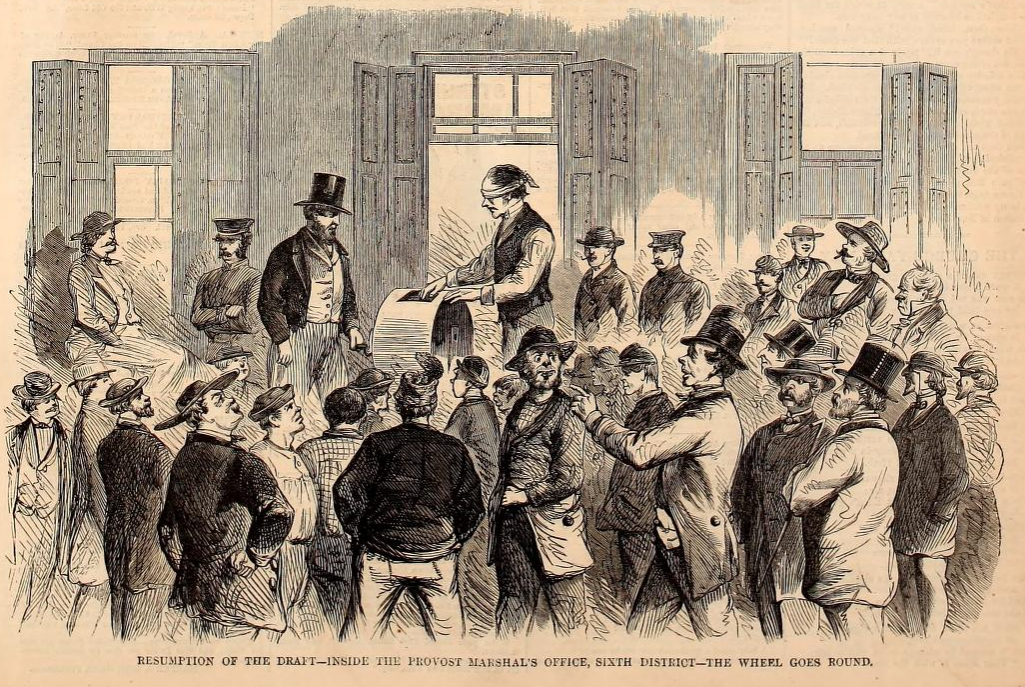

Examining surgeons, such as Stewart, faced many challenges in helping to run the new national conscription system. The Enrollment Act, signed by President Lincoln into law on March 3, 1863,[1] subdivided each state into districts, with each being governed by a three-man enrollment board. One of these three men was the examining surgeon; his role was ultimately to determine whether men – either draftees, substitutes (paid replacements for draftees), or recruits brought in under the auspices of the new law – were eligible for service in the Union army.

This was no easy task. National conscription was only introduced by Congress because volunteering in the Northern states had largely dried up by the winter of 1862-1863. Therefore, most drafted men had made a conscious decision to not enlist voluntarily and employed a multitude of tactics to claim medical exemption from service. Most men simply tried to overemphasize or exaggerate actual ailments. Some would hobble into the doctor’s office and point to an old scar, blaming it for their supposed lameness. Others, claiming chronic heart disease, would vigorously run around before an examination in order to get their pulse up in the hopes of fooling the examining surgeon. Some draftees, using a tactic that was easy to recognize, tried to exaggerate varicose veins by tying a rope tightly around one of their limbs for a few hours before examination.

Deafness and blindness were other common claims for exemption. Although these ailments were understandably difficult to prove false, examining surgeons gradually developed clever ways to determine if a man was lying. During his examination of a man in Massachusetts’ Fourth District who claimed to be “stone-deaf,” the surgeon muttered under his breath that it was “surprising [the draftee’s] knee has never caused lameness,” because “if the man had mentioned this there would have been no doubt about my ability to exempt him.” Apparently forgetting his previous claim of disability in his eagerness, the draftee blurted out that “it is true that I cannot walk at all, or for any distance, without lameness.” With the deafness disproved, the surgeon held him to service. For claims of blindness in an eye, one surgeon would make a draftee close his “good” eye while the examiner stood off to the side. He then ordered the draftee, “in a peremptory manner and sharp tone,” to look at him. If the sight was really gone, the eye would probably remain motionless, but a healthy eye would involuntarily snap in the surgeon’s direction.

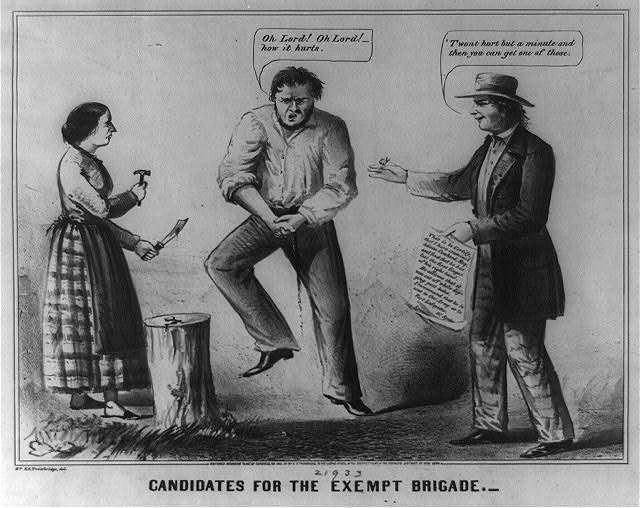

Others, such as the aforementioned Nicholas Wee of Minnesota, would deliberately harm themselves in order to avoid the draft. Men used cayenne pepper to inflame their eyes and claim conjunctivitis, or would rub irritant oils all over their limbs to simulate some sort of chronic skin disease. The latter ploy sometimes actually worked; despite generally knowing when these ulcers and irritations were self-inflicted, some of the injuries were so severe that surgeons had no choice but to exempt the draftees from service anyways. In the most extreme cases, men deliberately cut off fingers and toes before showing up for their exam.

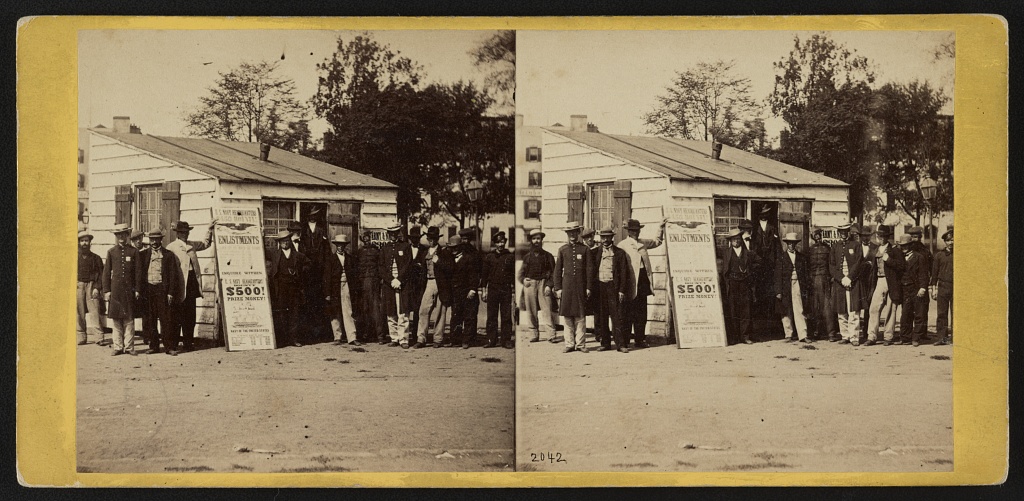

While draftees exaggerated or feigned maladies to avoid service, volunteers and substitutes did just the opposite: they purposely tried to hide ailments or mask their real age so that they could enter the Union army and collect large sums of bounty money. Many were either too young or too old and tried to alter their appearance so as to seem eligible; men over forty-five would “dye their hair, shave their faces smooth, and assume the firm and elastic gait of youth,” while “half-grown, beardless boys” tried their hardest to act maturely.

Some men with disqualifying conditions desperately tried to appear healthy in order to enlist and collect a bounty. Men iced hernias before an exam in order to reduce the swelling; put entire sets of false teeth made of vulcanized rubber in their mouths (masked by a quid of chewing tobacco); and even got drunk to hopefully mask lameness and stiffness or a “broken-down constitution.” For the most serious conditions, a common trick was for a perfectly healthy man to go through the examination under the assumed name of an ineligible recruit. After mustering in, the two would switch, and the previously-ineligible recruit would collect his bounties and don the Union blue.

As the demands for more men kept coming throughout the final months of the war, enrollment board surgeons faced an incredibly tough task. It was easier to examine draftees than substitutes and recruits – because the former generally made ailments more obvious while the latter tried to hide them – but most of the surgeons seemed to agree that even on a perfect day (with lots of help), they could only examine about fifty to sixty men. Despite the challenges, these surgeons performed an admirable duty in trying to see through the fraud and deception in order to get as many eligible men into the Union army as possible during the final months of the war. They were truly some of the unsung heroes in helping to defeat the Confederacy and end the Civil War.

Learn more in this interview with Nathan Marzoli, the post’s author

Sources

Statistics, Medical and Anthropological, of the Provost-Marshal-General’s Bureau, Derived From Records of the Examination For Military Service in the Armies of the United States During the Late War of the Rebellion, of Over a Million Recruits, Drafted Men, Substitutes, and Enrolled Men, Vol. 1. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1875).

Eugene C. Murdock, One Million Men: The Civil War Draft in the North (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1971).

[1] The law specified that all males between the ages of 20 and 45 were to be enrolled in two classes of draftee eligibility. Class One included single men from 20 to 45 and married men from 20 to 35, while Class Two included married men from 35 to 45. The men of the second class were not to be drafted until the first class were exhausted.

About the Author

Nathan Marzoli is a historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History in Washington, D.C., where he specializes in unit history and leads staff rides to Civil War battlefields. He has a BA and MA in History from the University of New Hampshire. His publications include “‘Their Loss Was Necessarily Severe:’ The 12th New Hampshire at Chancellorsville,” and “‘We Are Seeing Something of Real War Now:’ The 3d, 4th, and 7th New Hampshire at Morris Island, July-September 1863” (winner of the 2017 Army Historical Foundation’s Distinguished Writing Award). He is currently working on a study of substitutes in the Union army.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.