Table of Contents

Evacuating the Wounded

“The road was full of ambulances, artillery wagons, and horses and the shells were falling among them as fast as you could count… crashing through them and sending them in every direction.” — Private Lauren Gilbert, Ambulance Driver, 2nd Michigan Cavalry

Support the National Museum of Civil War Medicine

As Private Gilbert’s ambulance fled the scene from another Union Army defeat at Bull Run on August 30, 1862, he experienced the utter chaos of battle. Union lines were collapsing and everyone ran for safety, medical personnel included. Private Gilbert stopped to pick up two wounded soldiers on his desperate escape attempt aboard his regiment’s ambulance.

When he arrived at the remains of a bridge over Bull Run, an officer shouted for him to cross the creek. “That man has got wounded in his ambulance,” he exclaimed. As the world closed in on them, with Confederate soldiers pouring through Union lines and shells exploding all around, Private Gilbert recalled another man shouting to the wounded in his ambulance, “Don’t be afraid boys. God will take care of us.”

Over the course of the American Civil War, few changes in military policy were as dramatic as the evolution of the systems which removed wounded soldiers from the battlefield. While studies of the conflict often focus upon the movement of troops toward the front and how they were utilized when they arrived, examinations of the movement of those injured on the battle lines have received much less attention.

Yet, the improvisations and policies implemented during the conflict in regards to the extrication of wounded from the field are incredibly relevant to our own world in which mass casualty situations occur all-too frequently. The work of medical officers such as Major Jonathan Letterman in the face of staggering casualty figures as the war claimed ever more lives continues to transfix modern scholars. How did these officers do so much to shape an effective evacuation system in the midst of chaos and seemingly insurmountable challenges?

When war broke out in early 1861, military authorities in both North and South were ill-prepared for a large scale conflict. Look no further than the first major engagement between Union and Confederate forces on July 21, 1861 near Manassas, Virginia. Little centralized preparation for massive casualties was undertaken – it was up to the medical personnel from individual regiments to prepare for the coming engagement.

When the battle turned into a crushing defeat of Union forces, this lack of preparation in regards to evacuating the wounded proved disastrous. Surgeons had hired private contractors and teamsters to lead ambulance teams toward the fighting that fateful Sunday. When the battle turned in favor of the Confederates, these drivers were among the first to leave the field, removing their valuable ambulances from the place they were needed the most.

Dr. Frank H. Hamilton, writing five days after battle, noted the lack of transportation for the severely wounded. “In reference to the ambulances, the occasion of their absence … was simply, that the drivers became frightened, and to turn them back would have been impossible.” As a result, Dr. Hamilton noted that the wounded “were scattered the whole distance from Centreville to Washington,” without any way to facilitate their removal from the war zone.

Major changes to the medical service in the Union Army were not forthcoming. Despite efforts at reform throughout 1861 and early 1862, wounded soldiers were consistently left behind on the field of battle, received lackluster care when they made it to overwhelmed regimental hospitals, and then languished in facilities which lacked adequate supplies.

Evacuating the wounded from the field became a particularly thorny issue. With no one specifically detailed to carry wounded to the rear for treatment, soldiers at the front took the task upon themselves. There developed a mixture of good Samaritan instincts to help a fellow man and an easy opportunity to remove oneself from the danger of the battlefield which combined to limit military effectiveness.

In early summer 1862, the military medical apparatus in Washington received a shake-up courtesy of recently promoted Surgeon General William Hammond. The 34-year-old officer directed resources to assist in bolstering the nascent medical wings of the Union Army. In the news-worthy Army of the Potomac on the outskirts of Richmond, Virginia, this support came with the appearance of a new Medical Director. Major Jonathan Letterman had been appointed with a mandate to change the way this army cared for the wounded on the field of battle.

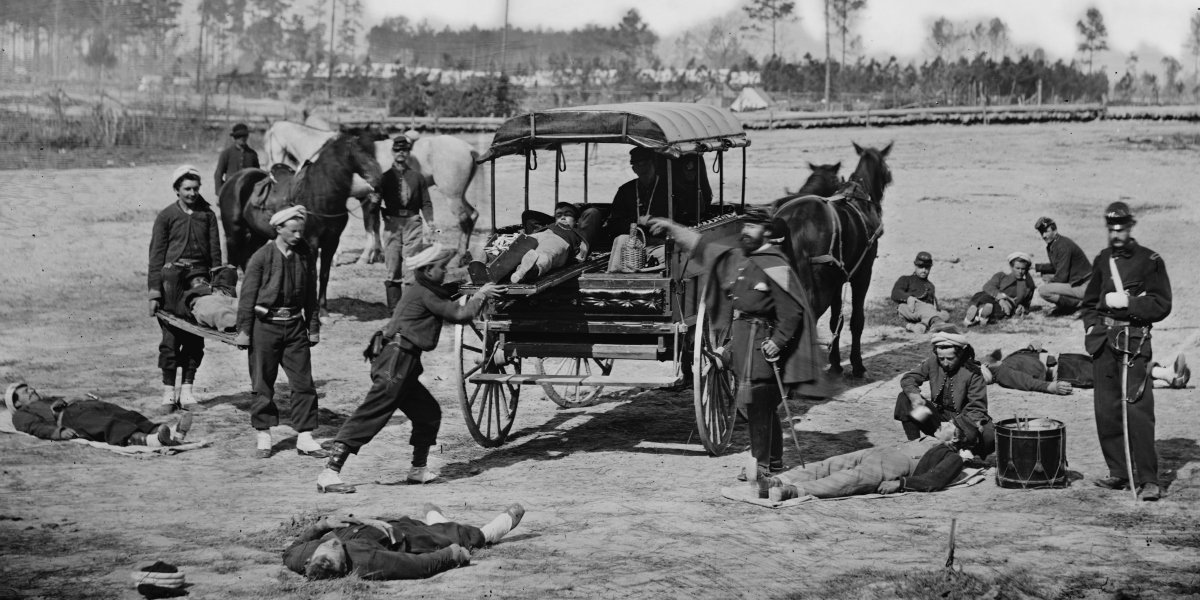

Through a number of circulars and in training sessions with newly appointed stretcher-bearers and ambulance drivers, Letterman was about to radically alter American medical history. He adapted systems of tiered-care first used in France, which would later be coined as “triage.” His ambulance drivers and stretcher-bearers were detailed for service near the front lines to quickly bring wounded away from the field. Letterman’s work in the summer of 1862 prepared his men for the horrors that were to come.

Unfortunately for Private Lauren Crocker and those on the battlefield of Second Bull Run, Letterman’s new system had not yet been adopted by the entirety of the United States Army. He was witnessing the chaotic last gasp of an army without an effective way to remove its wounded. In the next major battle that Crocker would experience, the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, Jonathan Letterman was destined to command the medical apparatus of the Army of the Potomac. His arrangement, later known as the “Letterman Plan,” was to be put to the test.

A revolution had begun that would save countless lives on the battlefield and change American emergency medicine forever. Letterman’s work in 1862 would later give him the impressive sobriquet: “Father of Modern Battlefield Medicine.”

About the Author

Jake Wynn is the Program Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He also writes independently at the Wynning History blog.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.