Table of Contents

Edwin Forbes, the Pry House, and the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam was probably the most picturesque battle of the war, as it took place on open ground and could be fully viewed from any point north of Antietam Creek, where our reserve batteries were posted. The battle was a dramatic and most magnificent series of pictures…

Thousands of people took advantage of the occasion, as the hills were black with spectators. Soldiers of the reserve, officers and men of the commissary and quartermasters’ department, camp-followers, and hundreds of farmers and their families watched the desperate struggle.

-Edwin Forbes

A link to more Forbes images is included below.

As the cannons roared on the ridges surrounding the Antietam Creek on September 17, 1862, spectators from miles around gathered to watch Union and Confederate forces engage mercilessly to potentially determine the fate of the American Civil War.

Many of them gathered on the property of Phillip and Elizabeth Pry; the high ground surrounding their farmhouse provided a nearly perfect vantage point to witness the spectacle. Among the visitors to the Pry property was Edwin Forbes, a renowned landscape painter and “special artist” for Frank Leslie’s Magazine. He and numerous other journalists gathered on the hilltops west and southwest of the Pry House to record the events that would come to be known as the bloodiest day in American history.

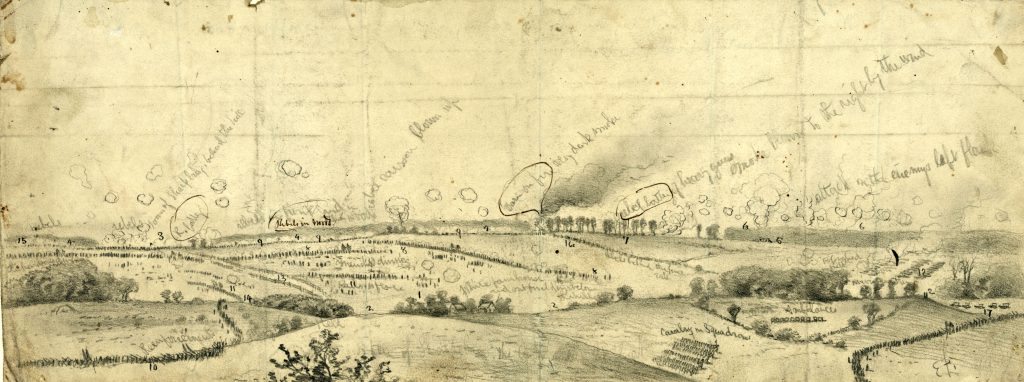

Forbes drew a sketch from his vantage point “west of the Turnpike,” and years later, utilized his notes to sketch the momentous events he had witnessed that day. What Forbes describes in his memoirs was the engagement at the very center of the battlefield that day.. Confederate forces had taken shelter amid a sunken road atop a ridge west of Antietam Creek.

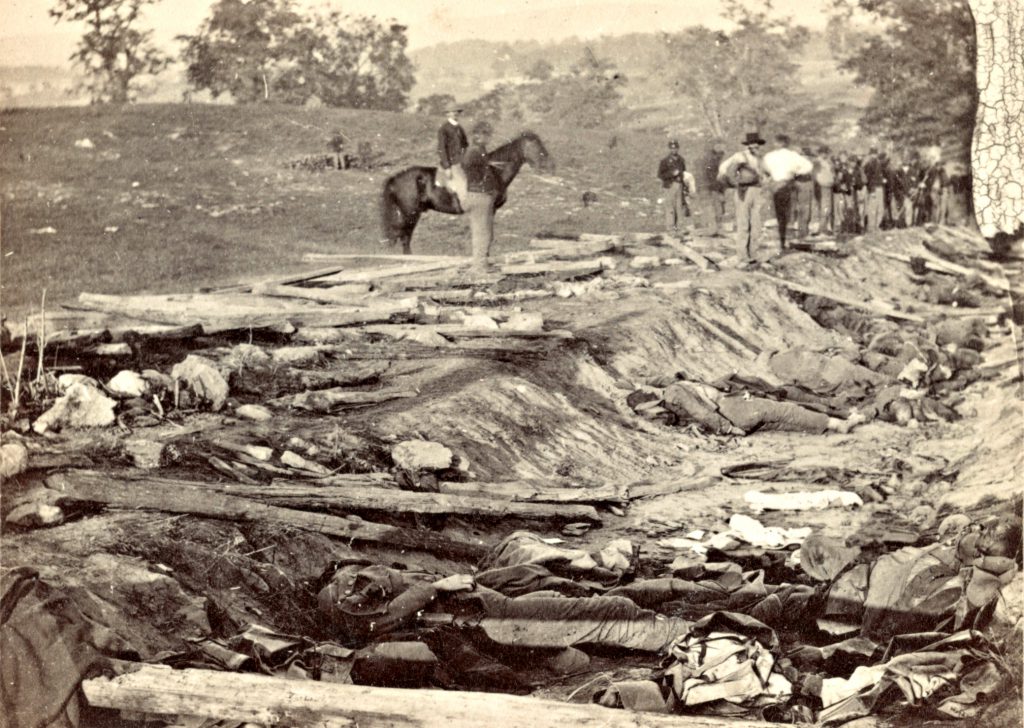

Two divisions of the Union Army emerged after crossing the nearby creek and went into battle. The fighting along that sunken road was so violent that area became known as “The Bloody Lane.”

Forbes described the sights he witnessed during the Battle of Antietam, writing:

Circumstances afforded me a fine opportunity of watching minutely the preparations of the Union Army previous to the battle of Antietam, also the grand advance and the terrible struggle of those brave men who dashed defiantly forward into a volcano of Southern fire.

The infantry was first ordered forward, and under the shelter of the trees of a wooded ridge of ground the men were formed in lines. The artillery was then posted in advantageous positions to cover the advance; while the cavalry found shelter from the opposing artillery fire until the outcome of the contemplated move could be determined.

A body of infantry skirmishers covered the front and at the word “Forward!” advanced and sent a responsive fire to every puff of smoke from the enemy’s skirmish line. The latter fell rapidly back toward the main position in a sunken road on the ridge. The main body of the Union forces formed in three lines, and moved slowly forward. The battle-worn and tattered flags floated in the sunshine, and the clanking accoutrements, rustling and tramping feet, and officers’ voices in command, mingled in one deep, strange sound, comparable only to the continuous roar of sea-surf at an incoming tide.

As soon as the enemy’s main line caught sight of our advancing host it gave greeting with a withering artillery fire; solid shot and shell ploughed lanes through the living mass. The scattering fragments of the shells that burst above the heads of our men did more execution than if they had exploded on the ground, and every solid shot, fired with a ricochet, bounded like a baseball, sending up a cloud of dust wherever it struck and sweeping everything in its course to destruction.

Despite this deadly work, how grandly our line advanced, and how calmly they closed up the gaps and moved on, leaving a blue trail of the fallen dead behind them!

But the enemy’s infantry fire soon became so severe that our advance line began to waver and show broken places. Looking through my field-glass I could see the mounted officers galloping up and down behind the troops, and the line-officers engaged in steadying the men as the showers of bullets swept across the ground in their front.

In examining the enemy’s position on the crest of the hill I could see their battle-flags quite plainly through the smoke; and, just appearing above the edge of a sunken road seemed to be a line of heads. Puffs of smoke played along them, varying at intervals in volume. Musketry fire could be plainly heard, the sound rising and falling from a terrific roar to a scattering fire…

Through my glass I soon saw hundreds of wounded men coming to the rear, some limping alone, others moving in groups, but all making for the same quarter, where they hoped to find relief. I saw also that our own lines began to lessen and great gaps appear. The Confederates had done deadly work, and off to the right of our forces several of their batteries had secured an enfilading fire along our front. As the grain bows before the scythe, so were our men in front felled to earth by the bursting shells sent at this murderous angle…

But our line of battle soon retired from its advance, and fell sullenly back to a retired position where they could halt and re-form. “Where is that gallant army,” I asked myself, “that but one short hour ago dashed so fearlessly into action?”

But a glance across the field in front of the enemy’s line told the sad story, for there lay brave men stretched in hundreds, sleeping their long last sleep; and many wounded had gone to the rear, some on foot who were able to walk, and those who were disabled had been taken in the ambulances. I looked at the sadly broken lines of the men who remained, with the thought that they would falter from further duty; but when I saw the blackened, resolute faces, and the quick, firm steps as they closed up the line, I felt that they possessed more than bravery – the soldier’s steady courage.

Reinforcements soon appeared, and our men, refreshed, started forward with renewed determination. The line breasted the hill once more, and with a rush dashed upon the enemy’s front, covering the last few hundred yards at a double-quick, and halting but an instant to discharge a volley in the face of the foe. Then the bayonets came into savage action, sweeping the enemy before them, broken and scattered. Those who escaped rushed back through an orchard in the rear, and, taking shelter behind some farmhouses and outbuildings, kept up a dropping fire on our troops; but it availed nothing, as the enemy’s center had been broken, and they fell back in confusion.

Forbes left the battlefield at Antietam and continued his work alongside the Union Army, his sketches giving the Northern public a view into the war raging across Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania.

Jake Wynn is the Program Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He also writes independently at the Wynning History blog.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.