Table of Contents

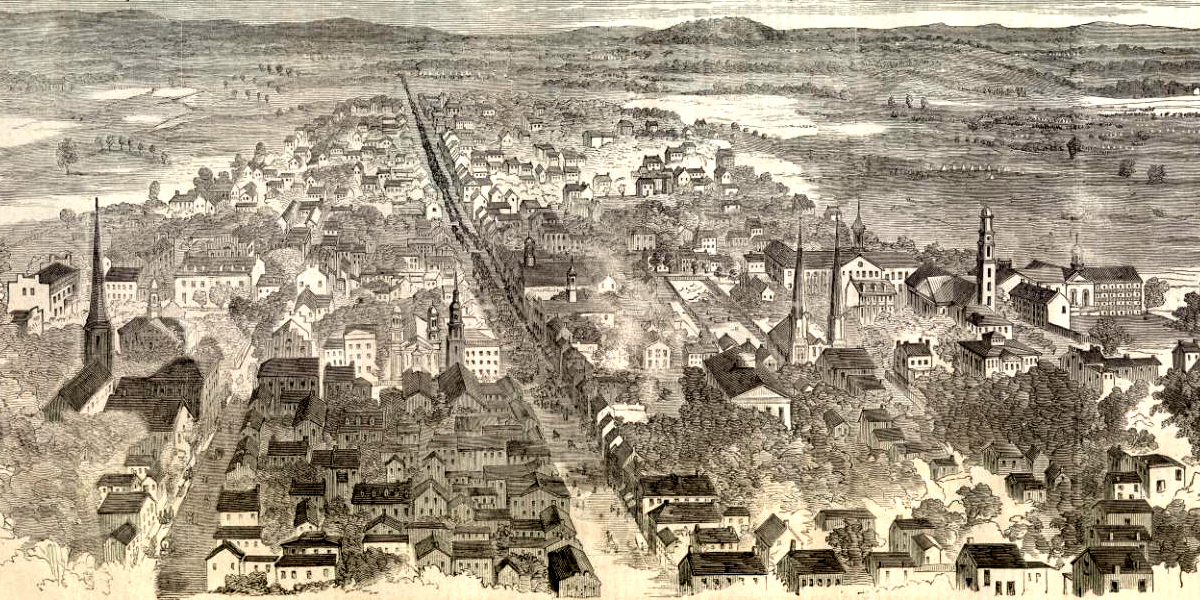

“When we first came here the streets, on a pleasant afternoon, were filled with convalescent wounded soldiers,” wrote Stephen Bogardus, Jr. in a letter to his hometown newspaper in late January 1863. His unit, the Purnell Legion, was assigned to guard the important railhead and road junction at Frederick, Maryland. They had been assigned to this non-combat assignment in early December 1862.

Remembering his arrival in Frederick on that assignment, Bogardus wrote of the numerous wounded men he witnessed everywhere in the town of 8,000 residents. “The bandaged head, the empty sleeve, and the stump of a leg, told a tale louder than words could speak,” he continued in his letter to the Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle. “Those who spoke flippantly of patriotism as a mere word should have seen some of those that I have met.”

The convalescing men Bogardus met on the streets of Frederick were just a few of the thousands who began their recovery from serious wounds and illnesses following the bloody fighting of September 1862. In the chaotic battles atop South Mountain and along the Antietam, more than 20,000 American soldiers fell wounded. Many were destined for make-shift hospital wards inside Frederick’s public buildings, schools, and hotels.

The autumn of 1862 witnessed an incredible transformation in Frederick. In the normally prosperous market community for local farmers, with a smattering of industry and access to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad just three miles south of town, almost all business had ground to a halt. Life in Frederick had been disrupted since early September, when the Army of Northern Virginia marched into town. Their occupation, lasting not quite a week, had summoned the Union Army from Washington, DC. The Army of the Potomac occupied Frederick on September 12.

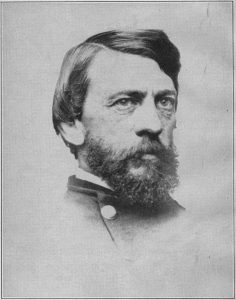

Arriving among the officer corps of the Union force was 37-year-old Major Jonathan Letterman, Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac. Letterman had a monumental task ahead of him as the army moved into Maryland. He and his medical department were responsible for the health of over 80,000 soldiers.

As Letterman entered Frederick on September 13, he ordered “the establishment of hospitals at that place for the reception of wounded in the anticipated battles…” This revolutionary action – the pre-staging of medical supplies and personnel prior to the outbreak of fighting – presaged more innovative steps to be taken by Letterman while in command of the Army of the Potomac’s medical wing.

Soon after the orders were issued, significant quantities of beds, bandages, anesthetic, and other medical necessities began arriving in Frederick. “All the churches (or nearly so) in Frederick have been taken for hospitals for the wounded which are to be brought to town,” wrote tailor Jacob Englebrecht in the morning of September 16.

According to Englebrecht, the first wounded from the Battle of South Mountain on September 14 arrived in Frederick aboard Army ambulances on September 17. He recorded that the churches-turned-hospitals were rapidly filling with wounded men.

The fighting near Sharpsburg (the Battle of Antietam) on September 17 only added to the length of the ambulance trains winding their way into Frederick. Medical Director Letterman acknowledged the challenges which needed to managed in the city in his after action report.

All the available buildings in this city (six in number) were taken at once for hospitals for our own troops and those of the enemy who should fall into our hands,” he wrote in his report. “These were fitted up with great rapidity… the buildings selected and prepared, beds, bedding, dressings, stores, food, cooking arrangements made, surgeons, stewards, cooks, and nurses detailed and sent for. This was a great deal of labor, but it was done, and done promptly and well.

By September 30, Letterman recorded there were already more than 2,321 patients in Frederick’s make-shift hospital wards. In addition to the temporary hospital wards, two tent hospitals were set up on the outskirts of the city. “In these hospitals and camps 62 surgeons, 15 medical cadets, 22 hospital stewards, 539 nurses, and 127 cooks were on duty,” Letterman reported. In addition to the 2,300+ patients received in hospitals downtown, the camp hospitals received 3,032 patients.

For the citizens of Frederick, this medical revolution prompted major changes to everyday life. “Town in commotion,” recorded Englebrecht in his diary on September 23. “Our little city is all day long & part of the night one continued bustle of moving of wagons, ambulances, etc. bring wounded, medical & hospital stores.”

While residents observed the commotion suddenly enveloping their community, others jumped into action. “As a vast number of sick and wounded are now in our midst requiring immediate relief,” wrote Mrs. J.A. Bantz, President of the Ladies’ Union Relief Association in the city “we would urgently entreat one and all of the friends of the cause, to renew their diligence and forward whatever they can… as our brave soldiers’ wants should be punctually attended to.”

Southern sympathizers also jumped into action for the wounded Confederate soldiers in the city’s hospitals. Catherine Markell made numerous visits to wounded Rebels in the autumn of 1862. She recorded visits in her diary, remarking sadly when soldiers died from wounds, infection, or disease. On November 24, she visited the Lutheran Church Hospital on Church Street before visiting Mt. Olivet Cemetery. “Visited cemetery, placed flowers on the graves of our friends of CSA who are buried there,” she wrote somberly.

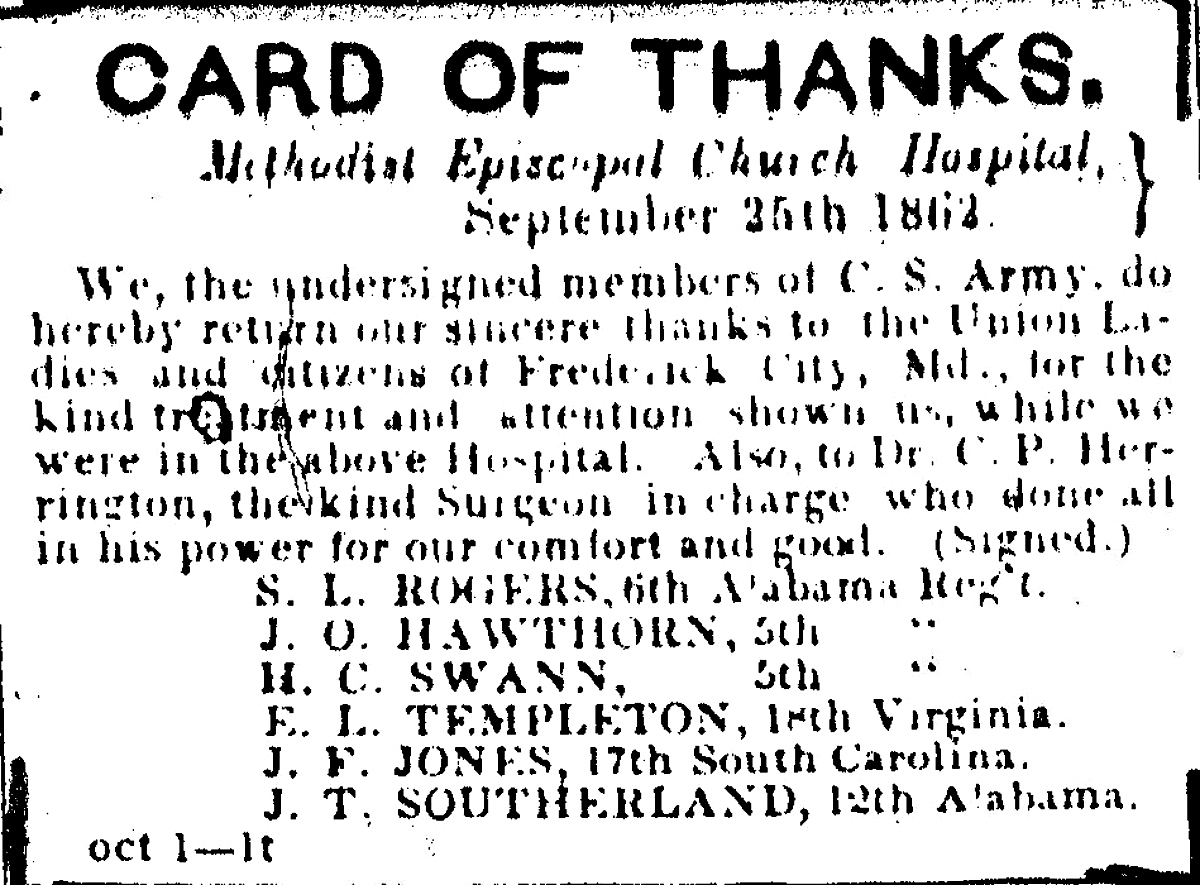

Despite the bleak situation as the weather turned cold in October and November, Frederick residents received high praise for their heroic actions in assisting the wounded in the city now labeled as “one vast hospital” by the Philadelphia Inquirer. One of those lavishing praise on Fredericktonians was a Baltimore preacher who wrote that, “the inhabitants of that city have covered themselves with a glory high above that of military conquerors, by their noble charities.”

All the while, Frederick residents dealt with the noise of passing ambulances, the illicit activities of those convalescing soldiers who were mobile enough to visit the city’s beer halls, and the ever-present Union military occupation. “Everything from the omni-presence of the soldier is tinged with blue,” one Pennsylvania soldier wrote in his diary. “Officers and privates crowd the sidewalk.” The intrusions of military and hospital into civilian life meant that for months, everyday life in the community came to a halt.

Over the course of four months between September 1862 and January 1863, Union Army surgeons recorded the treatment of more than 8,000 patients in Frederick’s hospitals. The life-saving care given in the city’s schools, churches, hotels, and private homes could not have been administered without the assistance of the local residents who nursed the wounded, amassed supplies, and carried on with life despite the horrors of war.

The wounded were removed from the city’s public spaces in January and February 1863 and were removed to general hospitals in neighboring communities for recovery. For those treated in the city, they would forever remember the assistance of the locals who volunteered at their bedsides.

Methodist Episcopal Church Hospital

September 25, 1862

We the undersigned members of C.S. Army, do hereby return our sincere thanks to the Union Ladies and citizens of Frederick City, Md., for the kind treatment and attention shown us, while we were in the above Hospital.

Als, to Dr. C.P. Harrington, the kind Surgeon in charge who done all in his power for our comfort and good.

(Signed)

S.L. Roger, 6th Alabama

J.O. Hawthorn, 5th Alabama

H.C. Swann, 5th Alabama

E.L. Templeton, 18th Virginia

J.F. Jones, 17th South Carolina

J.T. Southerland, 12th Alabama

About the Author

Jake Wynn is the Program Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He also writes independently at the Wynning History blog.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.