Table of Contents

Frederick, Maryland on September 17, 1862

The tramp of boots and the scraping of wagon wheels on paved city streets kept everyone aware of the situation. A great battle loomed on the horizon. Would it come today? Tomorrow? Had it already begun?

Frederick’s eight thousand residents awoke to the continuous noise of an army on the move in two directions on September 17, 1862. The tired, dust-coated faces of young soldiers in blue glided along Patrick Street headed westward on horseback.

Coming the other direction streamed an equally dirty, dejected group of men trudging into the city. Tailor Jacob Englebrecht noted their presence from his tailor shop on West Patrick Street. “The United States prisoners that were paroled at Harpers Ferry by General Thomas Jackson’s Army commenced arriving in town yesterday and this morning the New York 10th Regiment came in & one of them told me they were the last,” he wrote.

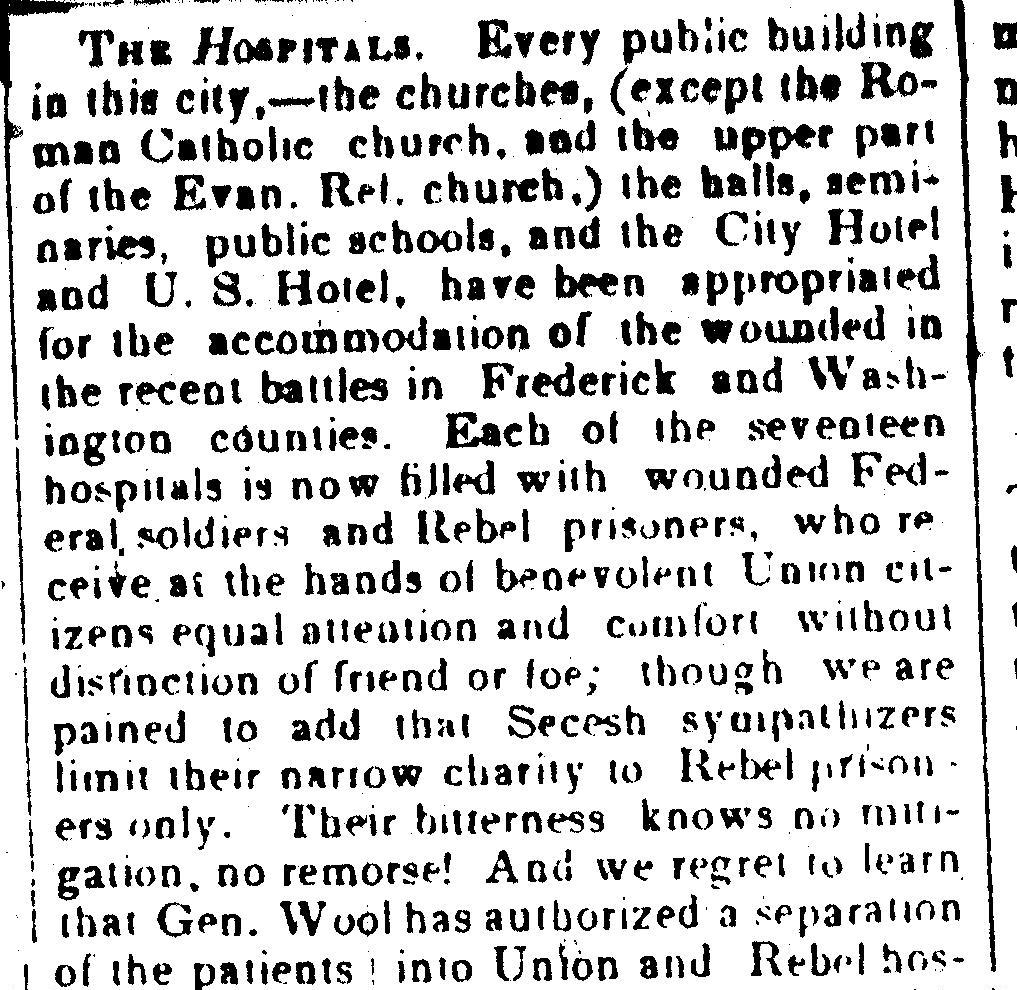

Englebrecht had noticed a day earlier that the city’s churches, including the German Reformed Church where he worshipped, had been taken over for Army service as hospitals “for the wounded which are to be brought to town.”

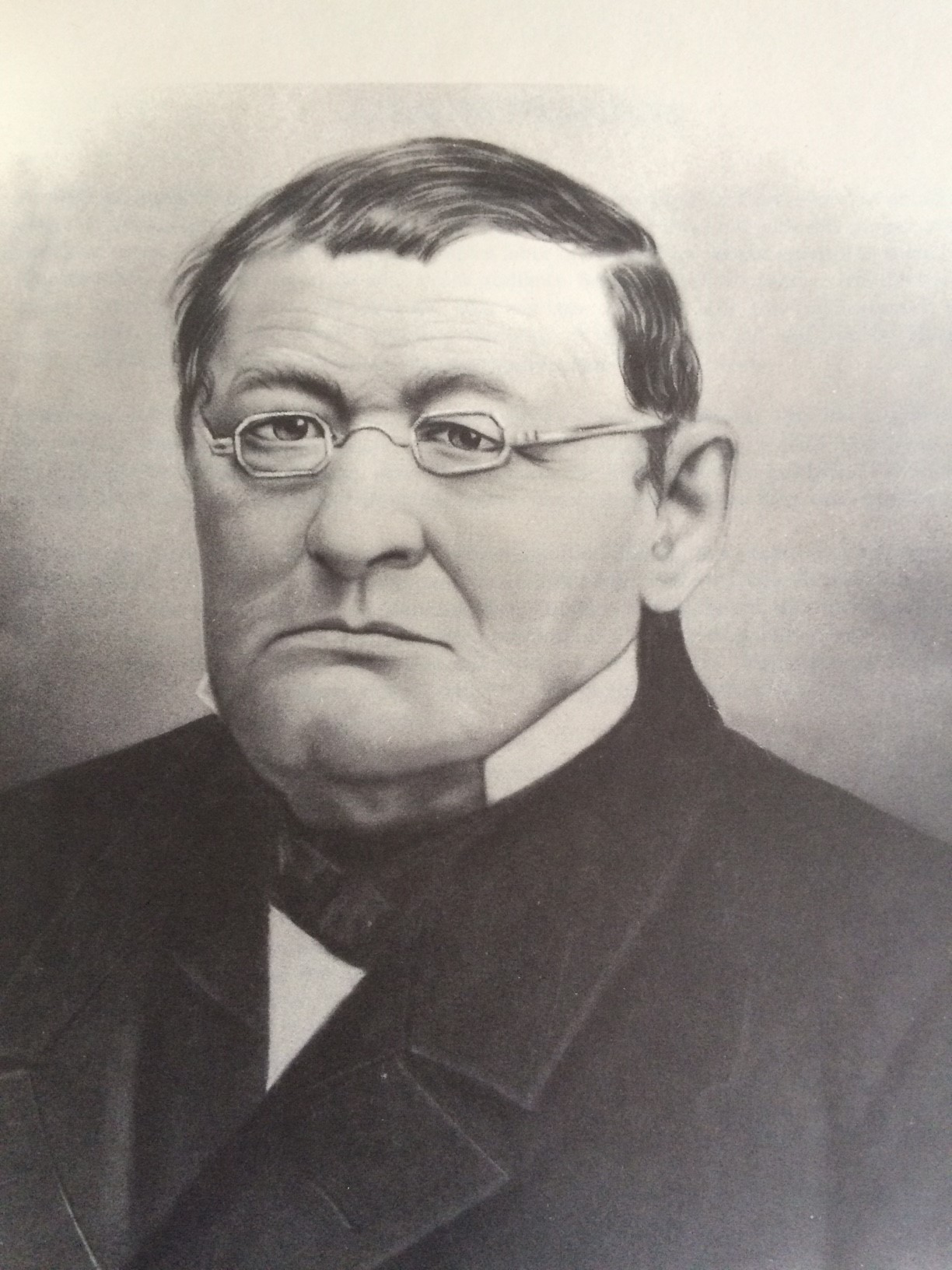

This had been ordered by the Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, Major Jonathan Letterman, during his trip through the city along with the staff of Major General George B. McClellan a few days earlier. “I directed the establishment of hospitals in [Frederick] for the wounded in the battles which were imminent,” Letterman later wrote. The spacious churches of Frederick, Letterman decided, would make for adequate hospital wards when the wounded were evacuated from the battles that were sure to come.

And those battles had indeed begun. On Sunday, September 14, the distant reports of artillery from the neighboring valley indicated that a severe engagement was underway. This was not the epic showdown Americans anticipated merely the bloody prelude known as the Battle of South Mountain.

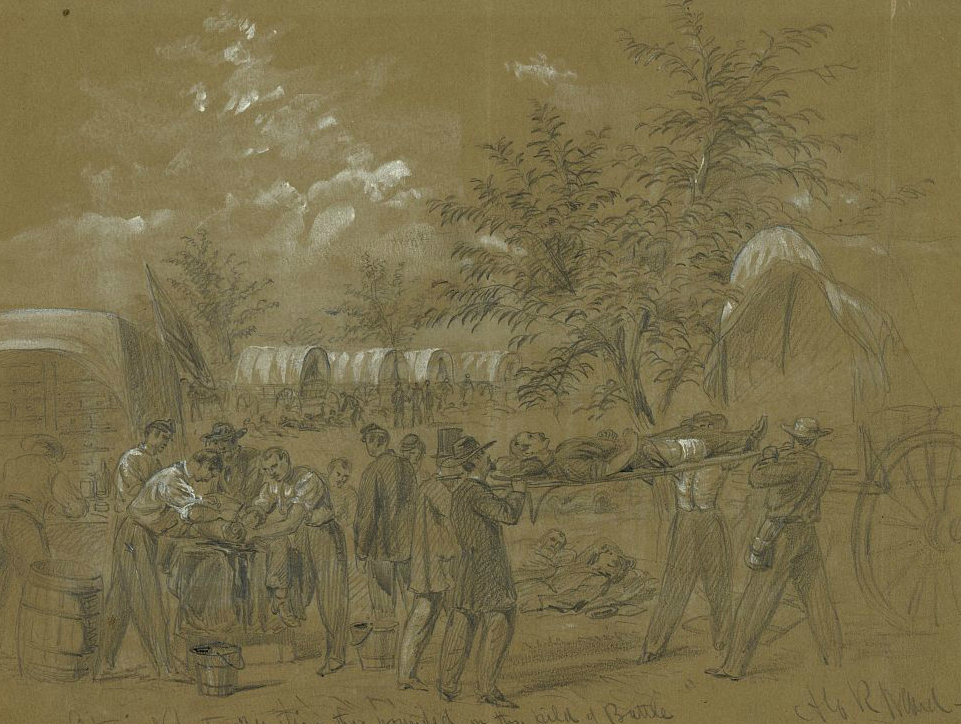

Sergeant Henry Tisdale of the 35th Massachusetts was among those who had traveled through Frederick and entered into the fray on South Mountain. For his troubles, he received a Minié ball through his left leg. After an ordeal on the mountainside, he worked his way into a Union field hospital. He was evacuated, along with hundreds of others, back to Frederick on September 17.

He was mixed in among the ambulance trains spotted by many Frederick residents as they slowly winded their way back to the city. “I counted 25 ambulances filled with wounded to be put in the hospital,” wrote Englebrecht. Others saw them, too.

Decades later, a woman could recall these moments from her childhood. “I can recall standing on Market Street… and how we used to watch the wagons bringing the wounded into Frederick for us to look after,” she wrote. “There was so much blood dripped out of the back of the wagons and falling on the dirt road, that eventually the mud became red as the wagon wheels ploughed through the streets.”

Medical authorities placed Sergeant Tisdale and other sufferers into the makeshift hospital ward at the Evangelical Lutheran Church on East Church Street. The photograph taken inside during these moments illustrates what Tisdale witnessed:

A rough board floor was laid over the tops of the pews. Folding iron bedsteads with mattresses, clean white sheets, pillows, blankets, and clean underclothing, hospital dressing gowns, slippers, etc. were furnished us freely. The citizens came in twice a day with a host of luxuries, cordials, etc. for our comfort. The church finely finished off within, well ventilated and our situation as pleasant and comfortable as could be made.

While troops continued to pass through the city and the wounded straggled in from the battlefield, a commotion grew over the telegrams and reports emerging from a new battlefield at Sharpsburg, 25 miles west of Frederick. “This city is very much excited, and all sorts of rumors from the battlefield are circulating,” wrote a reporter from the New York Herald on the evening of the 17th. “The latest and most reliable information to be had is derived from a gentleman who left the vicinity of the fight between two and three o’clock this afternoon.”

The reporter also noted that the Unionists of Frederick rejoiced at the word of a great Union victory and that several thousand Union troops passing through the city that evening “were enthusiastically greeted by the citizens, flags waved by ladies from the windows, etc.”

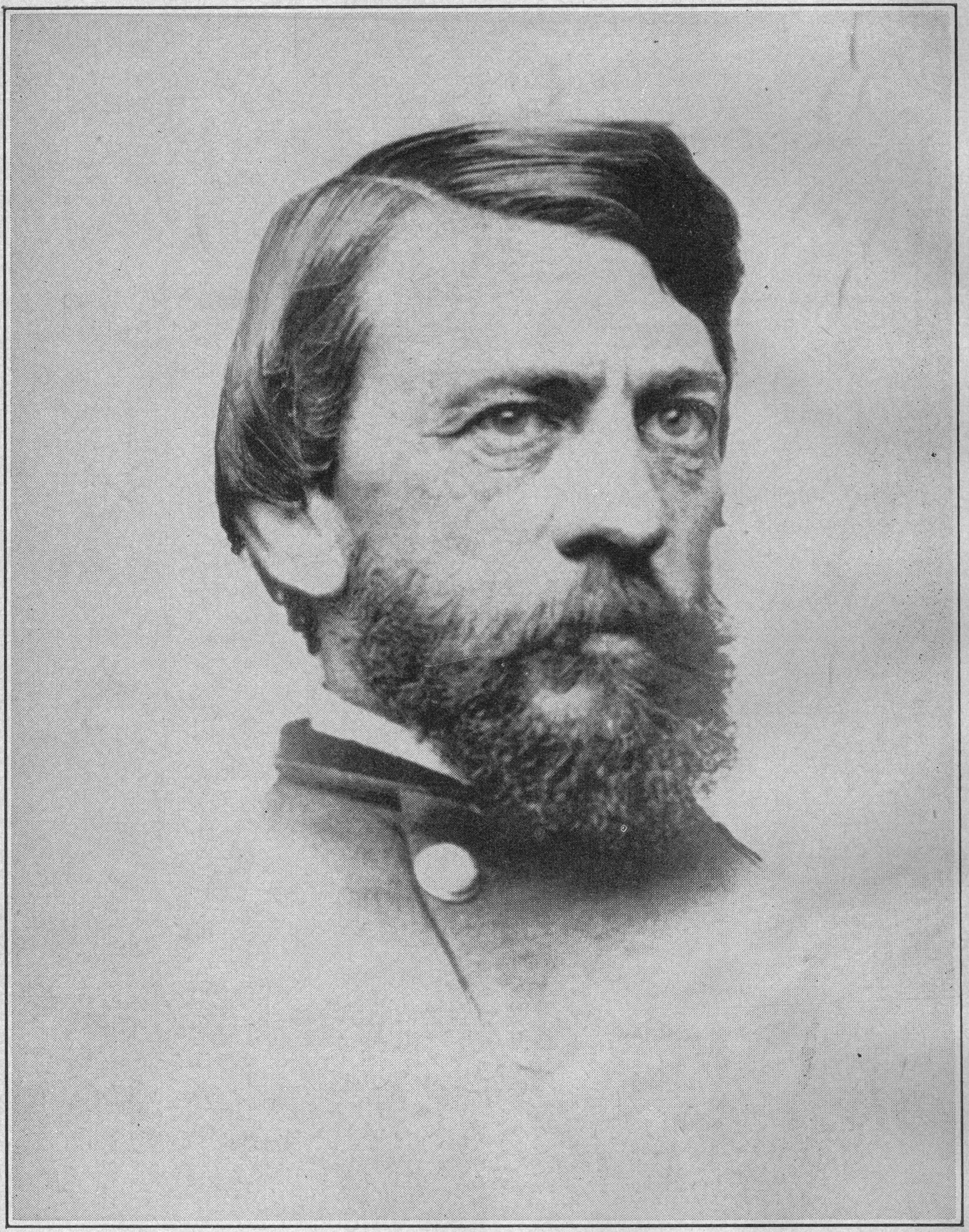

The rejoicing may have been premature. Medical Director Letterman sent word from the battlefield that he needed assistance. Within the day, Surgeon General William Hammond in Washington passed word to medical authorities throughout the Union states that surgeons were required immediately in Frederick.

“Dr. Letterman telegraphs for surgical aid, and says the need is urgent,” Hammond wrote in Washington. He began directing personnel to Frederick and within hours, surgeons from across the country were stepping aboard trains bound for Frederick, Maryland.

For the residents of the city, September 17, 1862 marked the transition from the excitement of being located at the seat of military activity to the slog of being a hospital city. Many must have gone to sleep that evening with thoughts of victory and the war’s conclusion on their minds. Yet, their hopes would surely be dashed, for the cruel reality of war was about to be thrust upon them.

In the following days, the city continued to swell with wounded and sick soldiers, Union and Confederate alike, and the town’s schools, churches, and public buildings had become surgical wards.

By September 24, the Frederick Examiner reported that the wounded already filled 17 buildings and remarked that “the thousands of sufferers, thrown by the emergency of battle upon this community, is a grievous tax upon the citizens, whose substance was nearly consumed by the hungry demands of the half starved rebels.”

For the next four months, more sick and injured men poured into town and additional buildings were required for Army needs. In total, almost 30 buildings were adapted for use as hospitals and, at times, the patients outnumbered the residents. The ordeal for the citizens of Frederick had only just begun.

Jake Wynn is the Program Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He also writes independently at the Wynning History blog.

For more information about Frederick’s time as a hospital city, check out Terry Reimer’s book, One Vast Hospital: The Civil War Hospitals Sites in Frederick, Maryland after Antietam.

Looking for a patient in Frederick’s Civil War hospitals? Click here to visit our searchable database of wounded soldiers with more than 9,800 soldiers who were treated in the city’s makeshift wards.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.