Good Death and Loss in the 19th Century

Many of the rituals that we now understand to make up the American funerary tradition were developed and shaped in the 19th century and have impacted how death is understood, discussed, and honored in our contemporary culture. The historical conception of “the good death” spoke to the experience of those were dying, but also shaped the mourning traditions of the living. While “the good death” is often thought of in historical terms, its rituals continue today.

“The good death” represented an ideal experience for someone that is prepared to die. First and foremost, this person would likely die at home, surrounded by loved ones. Before the professionalization of funeral directors at the end of the 19th century, death had always been handled at home. Family members would tend to the dying, comforting and tending to them in their final days and hours. It was thought that the dying would be able to impart a particular kind of wisdom that only comes at the end of one’s life, or perhaps offer apologies for wrongdoings or forgiveness to others.

New variations within religion influenced the way in which death was viewed. The newly influential liberal evangelical movement in the United States changed the way people thought of themselves as pious believers. “After 1850, the delicate balance of the evangelical era tipped away from fear and anxiety and toward assurance,” explained James Farrell.[1] Prior to this time, the role of religion only offered rigid guidelines in the ways in which one should worship and spoke little of any kind of joyful outcome after death: heaven was rarely discussed.[2] This changed in the 1850s. This new kind of assurance guaranteed that one would be rewarded with a pleasant afterlife. By living a life dedicated to moral goodness and the will of God, the event of death was not to be feared but rather, celebrated. Therefore, the living felt more confident that their recently deceased loved ones would go someplace without suffering or pain.

As the dying let out one final breath, it was the living that were able to mourn. Prior to the advent of embalming after the Civil War, it was up to the family, especially women, to wash and prepare their loved one for burial. In preparing the body, families worked against many natural factors, such as the impending rigor mortis—or stiffening of the body, and warm weather—which sped up biological decay. In a time where ice was not always readily available, it was crucial to bury the body in a timely fashion.

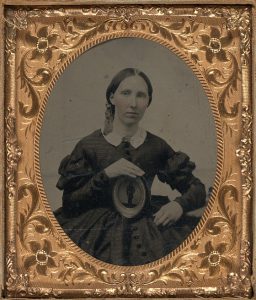

Mourning became a very public presentation of one’s loss, particularly through fashion. Customary garb for the grieving woman, sometimes dubbed “widow’s weeds,” was black and worn to represent the recent loss of a loved one such as a husband, parent or child. Varying according to class and locale, black dresses ranged from fairly basic to beautifully elaborate. Along with the dress, mourning garb included accessories such as shrouds, hats, and jewelry. Everyday accoutrements such as the handkerchief, would be re-embroidered with a black border to denote the new status of widow: “Even the smallest articles of clothing honoured the past and present stories of her loved ones.”[3]

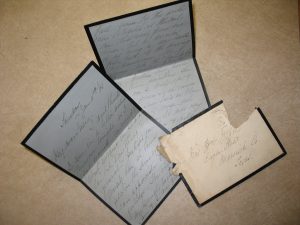

In the context of correspondence, even paper represented loss. Small, white cards had a simple black border; the envelopes matched. It is within these notes that death could be announced to those faraway. The stationery with the thickest border would be used for about a year, with the black border becoming thinner in the second year as an indication that the mourning period was drawing closer to an end.[4]

Men were not exempt from mourning rituals, but certainly had more flexibility in its presentation. Men were often expected to wear black suits or coats in mourning. This was less strict, and did not last as long; a widower mourned for three months after the loss of his wife, as opposed to two and a half years for women who lost husbands.[5] Some men sported a black armband to display that they were in mourning. This was seen in a large scale after the death of Abraham Lincoln in 1865, when the whole country entered into a phase of mourning.

Mourning went beyond clothing, expanding into the daily activities of the living. The handmade memorial was understood as a part of crafting, which included domestic activities such as quilting, sewing, or embroidering. These skilled crafts were a highly personalized approach to creating an object of commemoration. Many handmade memorials included common items such as dried flowers, paper collage techniques of other printed materials, handwriting, and precious objects. It provided a creative outlet for those suffering after their loss and is indicative of the Victorian era’s romanticization of death.

During this era, mourning also included photography. Postmortem photographs captured the likeness of the recently deceased. Photography was becoming more readily available by the middle of the 19th century, and to people of this era, the postmortem photograph was a common object. Often displayed in the home or shown to family members, a visual representation of a dead body was not surprising and was sometimes the only photograph that existed of the person. Coming out of an era where the dead were so often handled at home, seeing a photograph of the dead was likely to be more comforting than startling.

The notion of the “good death” was established in the early nineteenth century. Soon that notion would be challenged by the Civil War—where hundreds of thousands died on the battlefield, far from their families, and at a moment’s notice. It was impossible to enact the previous definition of the “good death” under those circumstances. Therefore, mourning practices and the ideal of the “good death” itself evolved so battlefield deaths could also be “good deaths.” The practices established during this time period continue to influence how we grapple with loss today.

About the Author

Kelly Christian is a Chicago-based researcher, writer, and artist. Her recent work explores postmortem and funerary photography. Kelly photographed military funerals in Maine during the height of the Iraq War and has created new media-Daguerreotypes. She has presented her work at conferences and galleries across the country on death and visual culture, 19th century funerary practices, and the history of embalming. She is a member of the Order of the Good Death.

Footnotes

[1] James Farrell. Inventing the American Way of Death, 1830-1920. (Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1980), 42.

[2] Harvey Green. The Light of the Home: An Intimate View of the Lives of Women in Victorian America.

(New York: Random House, 1983), 167.

[3] Melissa Zielke. “Forget-Me-Nots: Victorian Women, Mourning, and the Construction of a Feminine

Historical Memory.” Material History Review. Volume 58. Fall 2004. 56.

[4] Nigel Hall. “The Materiality of Letter Writing: A nineteenth century perspective.” In Letter Writing As A

Social Practice. By David Barton and Nigel Hall. (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub, 2000), 99.

[5] Drew Gilpin Faust. This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. (New York: Vintage Civil War Library, 2008), 148.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.