Table of Contents

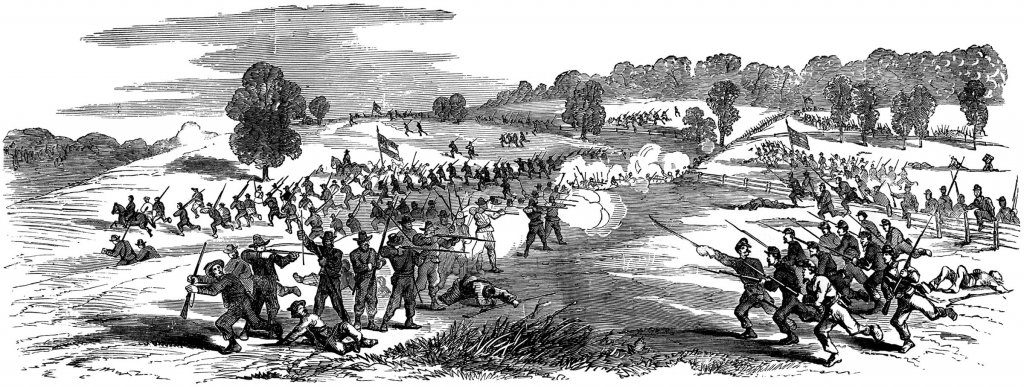

When the 23rd Ohio climbed the steep slopes of Maryland’s South Mountain in the morning of September 14, 1862, they were led by their 39-year-old regimental commander: Lt. Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes. Fifteen years before he would become president, the young commander took his unit toward the echoing sounds of the Confederate guns in Fox’s Gap, a mountain pass that carried a small road over the 1,000+ foot ridgeline.

This regiment would years later become known as the “President’s Regiment.” In addition to Hayes, there was a young commissary sergeant named William McKinley also assigned to the unit. Political ambition must have been far from their minds as the men of the 23rd struggled up the mountain toward battle on that bloody Sunday in September 1862.

Hayes led his Ohioans into battle at 9:00 A.M., attacking against the southern flank of Confederate forces in Fox’s Gap. “I feared confusion; exhorted, swore, and threatened,” Hayes wrote of his regiment’s arrival on the field of battle in relative disarray. He ordered an advance against Confederates behind a stone wall on top of the ridgeline. Union commanders needed Hayes’ men to pressure a regiment from North Carolina, which lay across an expanse of cornfield.

Shortly after giving the command for his unit to advance, Hayes “felt a stunning blow and found a musket ball had struck my left arm just above the elbow.” The stricken officer described what happened next in an entry in his diary:

Fearing that an artery might be cut, I asked a soldier near me to tie my handkerchief above the wound. I soon felt weak, faint, and sick at the stomach. I laid down and was pretty comfortable. I was perhaps twenty feet behind the line of my men, and could form a pretty accurate notion of the way the fight was going. The enemy’s fire was occasionally very heavy; balls passed near my face and hit the ground all around me. I could see wounded men staggering or carried to the rear; but I felt sure our men were holding their own. I listened anxiously to hear the approach of reinforcements; wondered they did not come.

Hayes had fallen wounded, stranded helplessly between Union and Confederate lines for about 20 minutes, when suddenly the shooting slackened. Hayes called back toward Union lines: “Hallo Twenty-third men, are you going to leave your colonel here for the enemy?”

Amid a renewed volley of Confederate musketry, the men of the 23rd Ohio rescued their leader from the field of battle. Behind the lines, Hayes’ brother-in-law and regimental surgeon Dr. Joseph Webb dressed his gunshot wound, administered opium and alcohol, and sent him off to the rear. An ambulance evacuated Hayes to Middletown, MD in the afternoon of September 14.

Hayes’ experience while being wounded and his relatively speedy medical attention resulted from the Army of the Potomac’s utilization of Medical Director Jonathan Letterman’s revolutionary system of evacuation. Back in Middletown, the medical authorities under Letterman adapted what they could for use as makeshift hospital wards. “Churches and other buildings were taken as far as were considered necessary, and yet causing as little inconvenience as possible to the citizens residing there,” Letterman reported in his official after-action report following the campaign.

The Army surgeon also detailed the organized system by which Hayes and more than 1,800 wounded Union soldiers were removed from the field of battle in that same report.

Houses and barns, the latter large and commodious, were selected, in the most sheltered places on the right and left of the field, by the medical directors of the corps engaged, where the wounded were first received, whence they were removed to Middletown, the Confederate wounded as well as our own. The battle lasted until some time after dark, and as soon as the firing ceased I returned to Middletown and visited all the hospitals, and gave such directions as were necessary for the better care of the wounded.

A major difference between the care for officers versus the enlisted men emerges when looking at the case of Lt. Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes. The ambulance that took Hayes to Middletown dropped him off at the home of Jacob Rudy. Officers like Hayes were often treated in private homes at their own expense, while enlisted men found treatment in communal wards located in churches, schools, and other large public buildings.

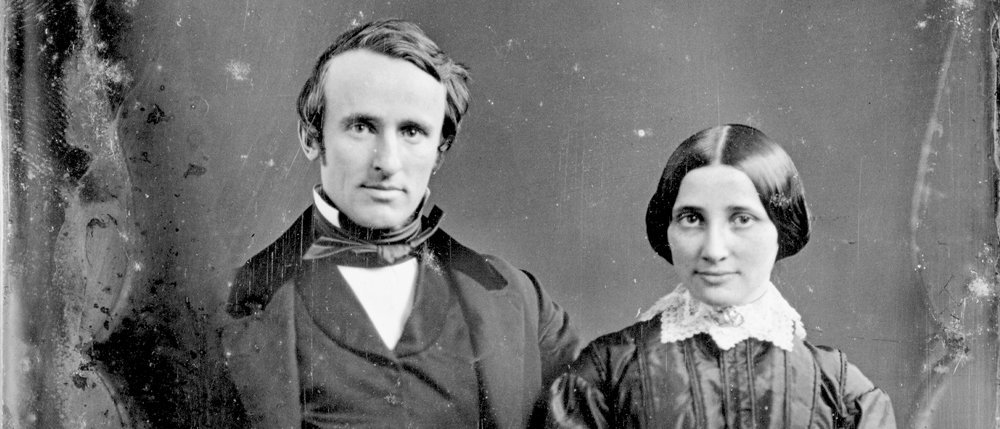

Shortly after his evacuation to the Rudy home in Middletown, Hayes endeavored to let his family know of his circumstance. He telegraphed home to Ohio to inform his wife, Lucy Webb Hayes, that he had been wounded. She left for Maryland immediately.

In a letter to his mother, Hayes described the nature of his injury as it began to recover. “I am steadily getting along,” he wrote. “For the most part, the pain is not severe, but occasionally an unlucky move of the shattered arm causes a good deal of distress.”

Lucy Hayes ventured toward the front in Maryland without having heard exactly where her husband was being treated. She scoured Army hospitals in Baltimore before heading toward the Rudy home in Middletown. Hayes fretted over whether or not she would find him. “This hurts me worse than the bullet did,” he jotted in his diary on September 20.

Mrs. Hayes arrived in Middletown on September 26, and began to nurse her ailing husband at once. In a letter to his uncle, Hayes wrote: “Lucy is here and we are pretty jolly,” he wrote. “She visits the wounded and comes back in tears, then we take a little refreshment and get over it.”

With help from his wife and the Rudy family, Rutherford B. Hayes quickly began to recuperate. By October 4, he had recovered enough to visit the South Mountain battlefield where he had been shot down. About two weeks later, he and Lucy headed home to Ohio to finish his convalescence.

His 23rd Ohio suffered badly at Fox’s Gap. Along with their commander, the regiment took another 130 casualties including 32 men killed, 95 wounded, and 3 missing. Most of the wounded were evacuated first to Middletown, and were later moved to hospitals in Frederick.

If not for the work of the surgeons and medical authorities under the command of Medical Director Jonathan Letterman, the suffering of those like Hayes and the men of the 23rd Ohio would have surely been greater. Though battles and campaigns continued to be chaotic affairs for the medical personnel of the Union Army, Letterman’s reforms sought to bring order and structure to medical treatment on the battlefield.

The Battle of South Mountain on September 14, 1862 proved an early test for Letterman and his newly trained personnel and can be considered largely successful. Letterman and his Medical Department built upon their accumulated knowledge at the subsequent Battle of Antietam and at subsequent engagements until the end of the war in the spring of 1865.

Promoted to colonel of the 23rd Ohio while recovering from his wounds, Rutherford B. Hayes returned to the regiment in December 1862. He suffered two more wounds during his service in the American Civil War. He was mustered out of Federal service in 1865 as a brevetted major general.

In March 1877, Rutherford B. Hayes became the 19th President of the United States.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.