Table of Contents

After the capture of Vicksburg, Mississippi on July 4, 1863, Union General Ulysses S. Grant was determined to end the prisoner exchange system that had existed since the beginning of the Civil War: “If we commence a system of exchange which liberates all prisoners taken, we will have to fight on until the whole South is exterminated.”[1] Secretary of War Edwin Stanton agreed with Grant that the Union should not be fighting the same soldiers over and over, and he ended all prisoner of war exchanges. As a result of this policy, thousands of soldiers were doomed to die in military prisons.

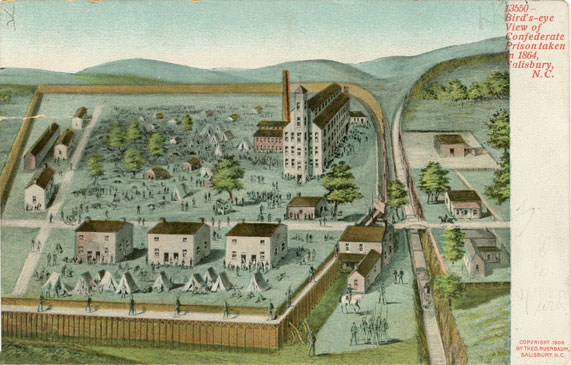

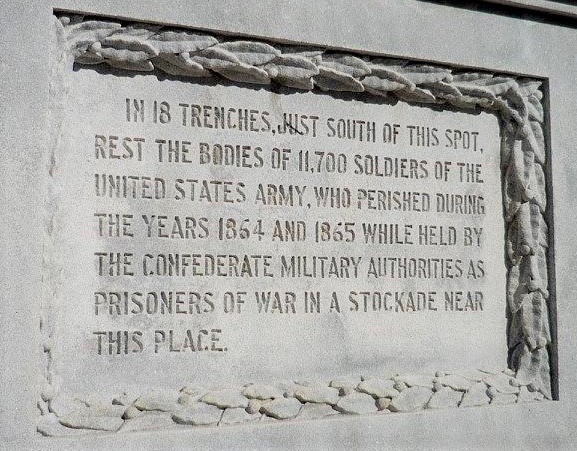

Despite being inundated with large numbers of prisoners, even the most notorious prison in the south, Andersonville in Georgia, attempted to provide hospital care for the thousands of prisoners housed in the stockade. Another infamous prison, Salisbury in North Carolina, also tried to treat its sick prisoners, with largely the same poor results.

Between October 1864 and February 1865, about every third prisoner who entered Salisbury prison died. According to the testimony of prisoners who were freed in May 1865, the number of deaths “owed more to the lack of shelter and of clothing than to lack of food.”[2] However, one prisoner commented: “What advantage had quinine and opium when they could get neither bread nor raiment?”[3] Whether lack of food was the main contributing factor to the death rate can be debated. What is undeniable is the number of sick prisoners. According to the Original Register of Federal Prisoners of War of the United States Confined in Prison Hospital, Salisbury, N.C., between 3,500 and 4,000 patients were admitted to the prison’s hospitals.

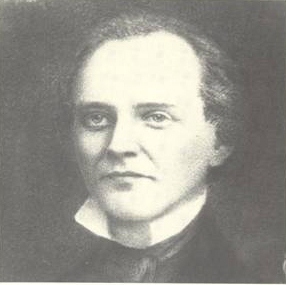

The Confederate surgeon in charge at Salisbury was Dr. Richard O. Currey, who was assigned there on July 20, 1864. As soon as he arrived, Dr. Currey compiled and sent a list of needed supplies to the state medical director. He also reported that 98 of the hospital’s 100 beds were filled. Prior to October 1864, there had not been a great need for a large prison hospital, but in early October, with the influx of 9,000 Union prisoners from the Petersburg campaign, Dr. Currey soon found that he was overwhelmed. He complained that he was the only doctor for the prisoners, and he again requested supplies, including additional beds, cook stoves, and medicinal brandy.

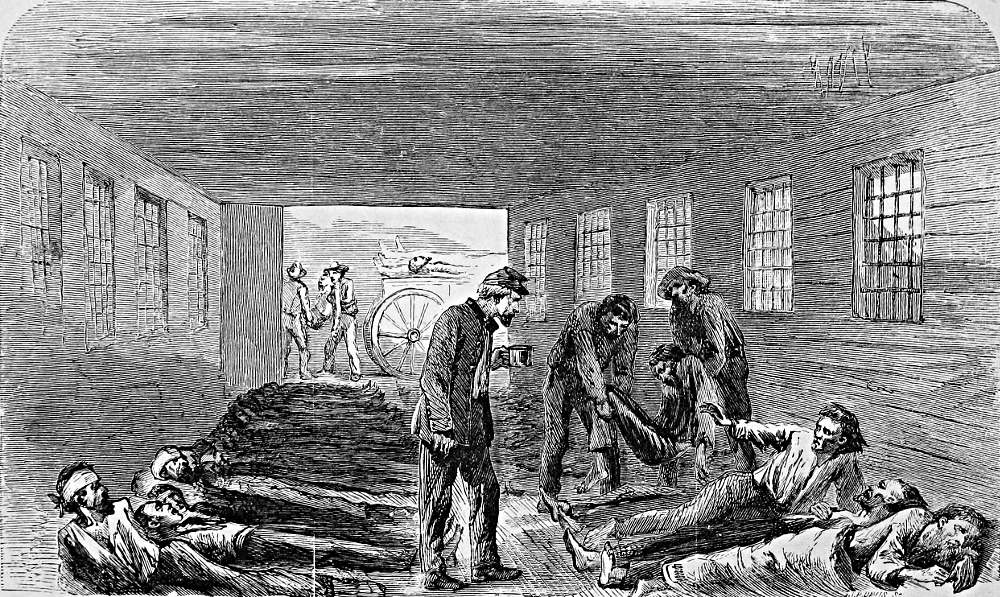

Additional buildings inside the stockade had to be used for hospitals. Straw was placed on the floor for the patients to lie on as only 100 bunks had been supplied out of a request for 450. The average number of prisoners being treated was around 700, with 500 more waiting for admission. Due to overcrowding, hospital gangrene spread amongst the patients, and the odors coming from the wards and nearby latrines were overpowering. Dr. Currey stated in his December 19, 1864, report that it was essential for the hospitals to be moved outside the stockade. A hospital for smallpox patients was established outside but prisoners began to use the “smallpox ruse”—burning small holes on their face and body using red hot needles to simulate smallpox sores—to get transferred to the hospital, where it was easier to escape.[4]

Union Pvt. Benjamin Booth, of the 22nd Iowa Volunteer Infantry arrived at Salisbury on November 4, 1864. In his diary, he describes the scene inside one of the prison’s hospitals:

[The sick were] placed in rows running the full length of the room. At one time a little straw partially protected the poor sick bodies from contact with the dampness and filthiness of the dirt floor, but the straw has become so broken and scattered by long use and no replenishment that it no longer affords any protection . . . On this floor the sick are laid in rows so closely packed together that there is no room to step between the bodies.[5]

Booth was particularly moved by the condition of men so sick that they could not keep the lice out of their mouths, eyes, or ears. Gangrene was prevalent among the sick prisoners and also in those suffering from exposure due to the lack of shelter. Booth writes in his diary on January 15, 1865 of seeing men whose hands and feet were rotting off. In some cases, the flesh had already fallen off, leaving the sinews standing out.

Another prisoner, Robert Drummond of the 111th New York Infantry, would go on a public speaking tour after the war, reporting on the starvation and disease endured by the prisoners of Salisbury. He reported that the hospitals were more like “sick pens” where “the wasted forms and sad, pleading eyes of those sufferers . . . will never cease to haunt me.”[6]

Clothing and shoes were collected from the dead and dying in the hospitals and redistributed to other prisoners. Sick prisoners who were not in the hospital would report to the doctor, who would give out either a pill for diarrhea or a cough medicine, which was given from a common tin cup. Both of these practices most likely contributed to the spread of disease in the prison.

The most common disease in Salisbury was diarrhea, which accounted for 43 percent of all the deaths. The unsanitary living conditions, as well as an inadequate supply of fresh water, was likely the cause of most cases. As there was not enough medication to treat everyone, and often the treatment was ineffective, prisoners turned to homeopathic remedies. There was a belief that tea made from oak bark would alleviate the symptoms of diarrhea, and Booth reports in his diary that “the trees within the stockade had their bark peeled off as high as a man could reach by standing on the shoulders of another.”[7]

Junius Henry Browne, a war correspondent for the New York Tribune who was captured by Confederates at Vicksburg, described his impression of Salisbury’s hospitals that were filled with patients suffering from diarrhea:

Hospital after hospital—by which I mean buildings with a little straw on the floor and sometimes without any straw or other accommodation—was opened, and the poor victims of Rebel barbarity were packed into them like sardines in a box. The hospitals were generally cold, always dirty and without ventilation, being little else than a protection from the weather. The patients—God bless them, how patient they were!—had no change of clothes, and could not obtain water sufficient to wash themselves. Nearly all of them suffering from bowel complaints, and many too weak to move or be moved, one can imagine to what a state they were soon reduced. The air of those slaughter-houses, as the prisoners were wont to call them, was overpowering and pestiferous. It seemed to strike you like a pestilential force on entrance; and the marvel was it did not poison all the sources of life at once.[8]

The second most deadly disease was pneumonia, which caused 11 percent of all deaths. This was due to the damp condition of the prisoners’ living quarters—which were often no more than holes dug into the ground with blankets for cover. There were only 300 tents provided during the winter of 1864, for almost 10,000 prisoners. In addition, a lack of firewood and scant clothing ensured many prisoners would suffer from exposure to the cold.

Typhoid fever was also wide-spread, and indeed, Dr. Currey himself would contract the disease and die from it on February 17, 1865 at Hospital Number 10 (the prison guards’ hospital) after only a few days illness. Overwork was most certainly a contributing factor to his death. Confederates were not immune to the illnesses that affected their prisoners. Some of the other common diseases that affected both prisoners and their Confederate guards included intermittent fever, scurvy, dysentery, pleurisy, and catarrh.

From 1861 to 1865, more than 150 prison camps were established by the United States and Confederate governments. The Official Record of the War of the Rebellion cites a total of 127,000 Union soldiers who endured being a prisoner of war. More than 22,580 of them died in prison, for a mortality rate of 18 percent.[9] Although hospitals were established in most of the prisons, it was clear that for various reasons they could not handle the sheer numbers of sick prisoners. The sick at Salisbury were victims of this deficiency. Junius Browne lamented this tragedy in his memoirs:

The hospitals could not contain one-eighth of the sick. They were in the tents, in caves, under buildings, and often bodies were dragged therefrom, and no names nor commands could be ascertained. Little, if anything, could be done for them medically. Hunger and exposure could not be remedied by the materia medica; and to seek to heal them by ordinary means, was like endeavoring to animate the grave.[10]

Sources

[1] Gerard, Philip; “The Dark Hole: Civil War Prison Camps;” Our State magazine, 2011

[2] Brown, Louis A.; Salisbury Prison: A Case Study of Confederate Military Prisons 1861-1865, 1992, page 131

[3]Brown, Louis A.; Salisbury Prison: A Case Study of Confederate Military Prisons 1861-1865, 1992, page 208

[4] Speer, Lonnie R.; Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War, 1997, page 210

[5] Brown, Louis A.; Salisbury Prison: A Case Study of Confederate Military Prisons 1861-1865, 1992, page 138

[6] Drummond, Robert Loudon; Personal Reminiscences of Prison Life During the War of the Rebellion, page 66

[7] Drummond, Robert Loudon; Personal Reminiscences of Prison Life During the War of the Rebellion, page 139

[8] Brown, Louis A.; Salisbury Prison: A Case Study of Confederate Military Prisons 1861-1865, 1992, page 207

[9] Haskew, Michael E.; “Prisons of the Civil War: An Enduring Controversy,” Civil War Quarterly, Summer 2013

[10] Brown, Louis A.; Salisbury Prison: A Case Study of Confederate Military Prisons 1861-1865, 1992, page 208

About the Author

Tracey McIntire earned her BA in English at Rivier College in Nashua, NH. She is Director of Communications at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, and an interpretive volunteer at Antietam National Battlefield. She is also an active Civil War living historian, where she portrays a woman soldier in various guises. Her ancestor, Pvt. Joseph Herrick, 32nd Maine Infantry, was imprisoned at Salisbury, where he died of disease on November 22, 1864.