Table of Contents

The Crimean War, fought from 1853 to 1856, was one of the bloodiest wars in the 19th century. As a result of having to deal with massive numbers of casualties, many medical innovations came out of the war. Florence Nightingale gained her fame by revolutionizing the nursing profession. There were also great technical innovations. One of these was the use of trains for transporting the wounded. This idea would find its way to America during the Civil War.[1]

In 1861, when the Civil War began, there were more than 30,000 miles of railroad tracks in the North, and only 8,000 miles in the South. While the North had a clear advantage, the South began to use its railroad system almost immediately for transferring troops and supplies. In fact, it was the use of the railroad by the Confederate Army that gave them a tactical victory at First Bull Run/Manassas. It wasn’t until January 1862 that President Lincoln authorized the U.S. government to take control of the railroads in the North. The first priority for the railroads was to ship army rations, followed by forage for the horses, ammunition, and then medical supplies.[2] The army quickly realized that they could make use of all the empty trains that were returning from the battlefields to transport the wounded.

The first medical evacuation by rail occurred after the battle of Wilson’s Creek in Missouri, on August 20, 1861. Wounded soldiers were taken from the battlefield by wagon more than 100 miles to the railroad depot at Rolla, where they were then loaded onto the bare floors of boxcars for the 110-mile journey to the general hospital in St. Louis.[3] The potential of this system of transport was quickly realized, but it was clear that it needed some work to make it more comfortable for the wounded.

These first hospital trains were nothing more than regular freight trains. Patients were placed in boxcars or baggage cars on wooden floors covered with straw, pine boughs, and blankets. Katherine Wormeley, a Sanitary Commission volunteer, described the wounded as being “put inside the covered cars—close, windowless boxes, sometimes with a little straw or a blanket to lie on, oftener without. They arrive a festering mass of dead and living together.”[4] In addition, the jarring of the train during the journey over uneven rails, combined with the jerking of the cars when stopping and starting, was an excruciating experience for the wounded.

These early converted freight cars could only comfortably accommodate nine patients, but some were packed with as many as twenty. Despite best efforts to cushion the ride for the wounded soldiers by providing overstuffed bed sacks on a thick pile of hay or straw, once the train was underway, the bedding quickly became matted down or scattered about. In addition, after a large battle, it was often difficult to get a sufficient supply of hay, so dry leaves or pine boughs were used instead.[5]

Adelaide Smith, who was a volunteer nurse at City Point Hospital described the arrival of these hospital cars:

The sight of these cars loaded with sufferers as they laid like logs, waiting their turn to be carried to the wards,–powder-stained, dust begrimed, in ragged torn and blood stained uniforms, with here and there a half-severed limb dangling from a mutilated body,–was a gruesome, sickening one, never to be forgotten, and one which I tried not to see when unable to render assistance.[6]

Because of these stressful conditions that the soldiers were exposed to, the early hospital trains would only transport those patients who were not seriously wounded and could tolerate the taxing journey.

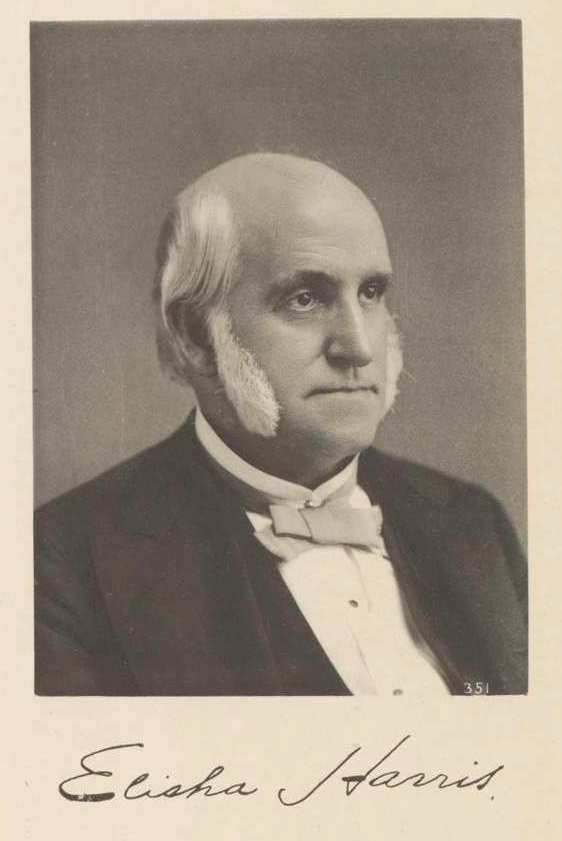

In June 1862, Dr. Elisha Harris of the U.S. Sanitary Commission was riding one of the converted freight trains and witnessed first-hand the suffering of the patients. He decided that the cars could be redesigned to better accommodate the wounded and to provide a more comfortable ride. Harris designed a system for hanging stretchers with India rubber rings to serve as shock absorbers.[7] He submitted this design to Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs, who approved it and ordered that construction of the cars begin immediately.

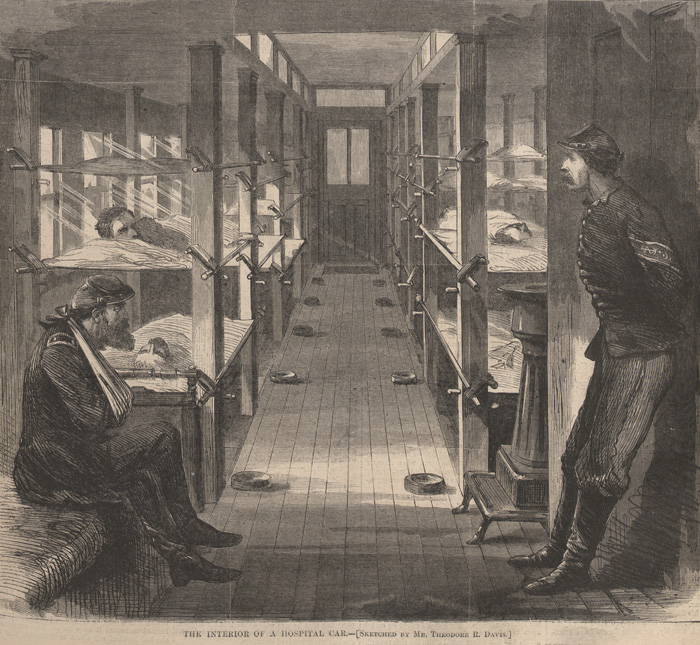

The Harris hospital car was a 51-foot-long passenger car that was fitted with upright posts to accommodate three tiers of stretchers. A total of 36 patients could fit in each car. The patient could be taken directly from the ambulance, and the poles of their stretcher would fit directly into the rubber rings on the posts. This greatly simplified the loading and unloading of the wounded, as they did not have to be transferred from a stretcher to a bed. It also made the journey much more comfortable by minimizing patient movement. The Harris car also made it possible for surgeons and other medical personnel to go from car to car to tend to the patients, something that had not been possible with a converted freight car. The medical personnel were given seats at each end of the car. A stove and kitchen area stocked with food and utensils, a water tank, a dispensary area, and a toilet were also available in each car.[8] The dispensary would provide medicines, towels, socks, and blankets and the kitchen would offer food and beverages.[9] Sanitary Commission workers, in addition to military medical personnel, would tend the wounded.

Georgiana M. Woolsey, of the United States Sanitary Commission, wrote of her experience with the hospital trains as they transported the wounded back from the battle of Gettysburg in 1863:

A Government surgeon was always present to attend to the careful lifting of the soldiers from ambulance to car. . . When the surgeons had all the wounded placed, with as much comfort as seemed possible under the circumstances, on board the train, our detail of men would go from car to car, with soup made of beef-stock or fresh meat, full of potatoes, turnips, cabbage, and rice, with fresh bread and coffee, and, when stimulants were needed, with ale, milk-punch, or brandy . . . I do not think that a man of the sixteen thousand who were transported during our stay, went from Gettysburg without a good meal. Rebels and Unionists together, they all had it, and were pleased and satisfied.[10]

By the spring of 1864, a network of hospital trains for the Union had been established in both the Eastern and Western Theaters. In the Eastern Theater, Surgeon Robert Abbott, Medical Director of the Department of Washington, proposed the use of a dedicated hospital train that would not only transport patients, but also provide for medical care along the way, similar to a modern M.A.S.H. unit.[11]

These newly designed hospital trains typically consisted of one box car, a kitchen car, a regular passenger car, five cars with beds, an office car, and a conductor’s car. The box car would be used to store baggage as well as food stores, which included meat, coffee, sugar, flour, seasonings, vegetables, molasses; and other essentials such as soap and candles.[12] The locomotive was specially marked to indicate that it was pulling a hospital train: the smokestack and tender were painted scarlet and gold. At night, three red lanterns were hung below the headlight on the front of the train.[13] All of the other cars would be marked “U.S. Hospital Train” in large red letters. These markings apparently worked as there is no recorded incident of a hospital train being intentionally fired upon.

A Sanitary Commission worker in the Western Theater who rode one of these hospital trains described her experience:

I had the privilege of a ride on a hospital train from Chattanooga to Nashville, and an opportunity of seeing the plan of arrangement of the train. Imagine a car a little wider than the ordinary one, placed on springs, and having on each side three tiers of berths or cots, suspended by rubber bands. These cots are so arranged as to yield to the motion of the car, thereby avoiding that jolting experience even on the smoothest and best kept road . . . There were three hundred and fourteen sick and wounded men on board, occupying nine or ten cars, with the surgeon’s car in the middle of the train . . . A narrow hall connects the store-room and kitchen, and great windows or openings in the opposite sides of the car give a pleasant draft of air . . . The men come on [the train] at evening . . . and after having had their tea, the wounds have to be freshly dressed. This takes till midnight, perhaps longer, and the surgeon must be on the watch continually, for on him falls the responsibility, not only of the welfare of the men, but of the safety of the train. There is a conductor and brakeman, and for them, too, there is no rest. Each finds enough to do as nurse or assistant. In the morning, after a breakfast of delicious coffee or tea, dried beef, dried peaches, soft bread, cheese, etc., the wounds have to be dressed a second time, and again in the afternoon, a third.[14]

While the evolution of hospital trains in the North greatly improved the treatment and conditions of the patients, the South was never able to achieve the same level of advancement, mostly due to the lack of supplies. Dr. Hunter McGuire, Medical Director of Stonewall Jackson’s Corps wrote:

We used freight cars in transporting wounded men, and sometimes sick men, using straw or leaves for bedding. Stretchers were very scarce . . . sometimes we suspended one of them by ropes fastened to posts on the side of the car. We had few ropes, and no rubber rings. Passenger cars were also used. Planks were fastened on the tops of the backs of the seats; these slats were covered with beds, upon which the patients were laid.[15]

The Confederacy, while not able to benefit from the advanced design of the North’s hospital cars, nevertheless did run a regular schedule of hospital trains, especially in Virginia, evacuating the wounded from field hospitals to general hospitals.

The idea of using trains to transport wounded, and as mobile hospitals, was just one of the many technological innovations resulting from the Civil War. The hospital train would go on to be an essential part of the military during World War I and II, and the Korean War. With today’s modern modes of transportation, they have become mostly obsolete, but 160 years ago, the hospital trains were responsible for saving hundreds of lives.

About the Author

Tracey McIntire earned her BA in English at Rivier College in Nashua, NH. She is Director of Communications at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, and an interpretive volunteer at Antietam National Battlefield. She is also an active Civil War living historian, where she portrays a woman soldier in various guises.

Sources

[1] Heatley, Lorna. “Hospital Trains throughout the ages,” Rail Discoveries web site, April 5, 2018

[2] Steinbach, Trevor. “Union Hospital Trains in the Civil War,” Timelines Magazine, Oct. 12, 2020

[3] “An ambulating hospital: or, how the hospital train transformed army medicine,” The Free Library, Kent State University Pres, Oct. 24, 2022

[4] “An ambulating hospital: or, how the hospital train transformed army medicine,” The Free Library, Kent State University Pres, Oct. 24, 2022

[5] Ibid.

[6] “An ambulating hospital: or, how the hospital train transformed army medicine,” The Free Library, Kent State University Pres, Oct. 24, 2022

[7] Puzzilla, Anthony G. Hospital Trains and Vessels During the Civil War, 2020, page 53

[8] Puzzilla, Anthony G. Hospital Trains and Vessels During the Civil War, 2020, pages 53-54

[9] Ibid. Page 57

[10] Brockett, L.P. Woman’s Work in the Civil War: A Record of Heroism, Patriotism, and Patience, 1867, pages 339-340

[11] “An ambulating hospital: or, how the hospital train transformed army medicine,” The Free Library, Kent State University Pres, Oct. 24, 2022

[12] Puzzilla, Anthony G. Hospital Trains and Vessels During the Civil War, 2020, page 165

[13] “An ambulating hospital: or, how the hospital train transformed army medicine,” The Free Library, Kent State University Pres, Oct. 24, 2022

[14] Brockett, L.P. Woman’s Work in the Civil War: A Record of Heroism, Patriotism, and Patience, 1867

[15] Puzzilla, Anthony G. Hospital Trains and Vessels During the Civil War, 2020, page 206