Table of Contents

The American Civil War brought the hypodermic syringe “into the mainstream of American medicine for the first time.”[1] A new and still uncommon instrument, its use by some US Army surgeons opened the gates for the widespread adoption of this vital tool.

The hollow metal needle was invented in 1844 by Irish physician Francis Rynd, who used a suction tube for administering morphine.[2]

Two versions of a syringe to accompany the needle were independently invented by scientists in 1853. Charles Gabriel Pravaz invented a silver tube syringe that used a screw mechanism to carefully control the dosage, while Alexander Wood used a glass tube that allowed the physician to see how much was in the syringe and a plunger.[3]

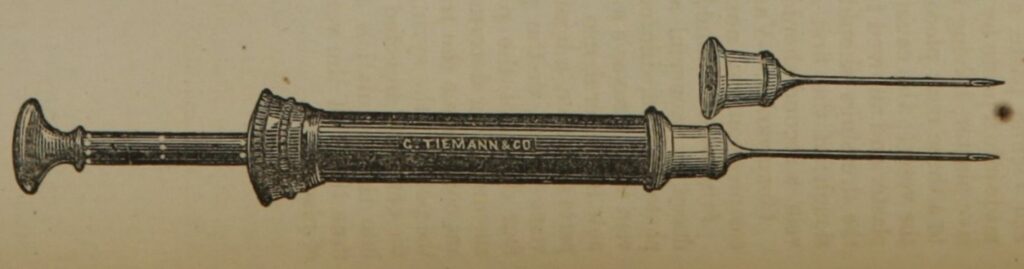

Wood’s design eventually won out and became the prototype for hypodermic syringes in use today, but both models were produced and used during the Civil War. Stephen Smith in his 1862 Hand-Book of Surgical Operations, recommended the Pravaz syringe and included an engraving of the Tiemann & Co. version. Dr. Smith went so far as to assert that this device was “now in general use.”[4] How true that was is up for debate.

The invention was still new by the outbreak of the Civil War. Indeed, the term “hypodermic” wasn’t coined until 1859.[5] Over the course of the War, the U.S. Army distributed only 2,093 hypodermic syringes.[6]

With government supplied syringes, some American physicians gained access to the new instrument, but not all. How much access surgeons had to hypodermic needles during the war is unclear, but historian David Courtwright argued that “it is virtually certain…that [hypodermic syringes] were in the minority” when it came to medical instruments. The authors of the Medical and Surgical History claimed that “the hypodermic syringe had not yet found its way into the hands of our officers” and that “it was not until after the close of the war that hypodermatic medication began to be discussed in our medical journals.”[7]

The Medical and Surgical History contradicts itself in a preceding volume by listing cases in 1862, 1863, and 1864 that utilized hypodermic needles.[8] One U.S. surgeon, Silas Weir Mitchell, asserted that his hospital delivered forty thousand injections over the course of the war.[9] Courtright is probably correct that needles were not widespread, but they were used. U.S. surgeon and Civil War veteran W.W. Keen may have said it best in a speech he delivered in 1918: “The hypodermic syringe was so new in the ‘60s that the number of army surgeons who had them probably did not exceed the numbers of fingers and toes together.”[10]

Among those lucky few was Keen himself, who worked at the same hospital as Mitchell.[11] Turner’s Lane Hospital in Philadelphia, a specialty hospital for treating injuries and diseases of the nervous system, was well equipped with syringes, and those forty thousand injections that Mitchell referenced were conducted there. A study published after the war by the surgeons of Turner’s Lane was an important text in the acceptance of hypodermic syringes by the larger American medical community.[12]

Though sources are scarce, it appears that Confederate surgeons were almost entirely bereft of hypodermic syringes. One surgeon in the Army of Tennessee, Dr. R.D. Jackson, was lucky enough to secure one through his own channels. He later remembered: “I never had seen one, but thought from what I had heard about it that it would be very useful in relieving the wounded soldiers of pain…I exhibited it to my friends—the surgeons there, eighteen in number—none of them had ever seen one before.”[13]

Unlike modern syringes, these instruments were intended to be reused many times over on many patients. In a pre-antiseptic age, this led to inevitable infections. Mitchell wrote: “The injections gave rise to occasional abscesses, and in a soldier who was at one and the same time the subject of a very painful wound of the arm, an[d] of a cold abscess on the back, every injection gave rise to a large indolent abscess. One instance of erysipelas following the use of an injection was seen by us.”[14]

Another consequential difference between syringe use at the time and today was where injections were administered and how. Patients were permitted to self-inject after getting some instruction from physicians, and in the words of William White: injections “were either subcutaneous (under the skin) or intramuscular (in the muscle).” It would be another sixty years before intravenous (in the vein) injections were commonplace.[15]

Hypodermic injections were not yet used for vaccinations, which were still administered with a lancet. Dr. Middleton Goldsmith’s successful use of bromine to treat hospital gangrene was delivered through hypodermic injection when surface treatment failed.[16] In 1860, the southern physician Dr. Henry Campbell used injections of caffeine on overdose patients as part of a resuscitation procedure.[17]Aside from Dr. Goldsmith’s treatment and Dr. Campbell’s questionable procedure, syringe use was almost universally reserved for delivering pain relief, and the only truly effective painkillers of the 1860’s were opiates.

Hypodermic needles greatly accelerated the opium epidemic that follow the Civil War. Many of the victims were soldiers, but the surgeons could also suffer from addiction. Dr. Mitchell, perhaps the most experienced physician in the use of the hypodermic syringe, wrote a semi-autobiographical narrative in 1892 detailing the ravages of opium addiction: “If any man wants to learn sympathetic charity, let him keep pain subdued for six months by morphia, and then make the experiment of giving up the drug….The nerves, muffled so to speak, by narcotics, will have grown to be not less sensitive, but acutely, abnormally capable of feeling pain, and of feeling as pain a multitude of things not usually competent to cause it.”[18]

Today’s medical personnel use hypodermics for everything from administering pain medication to giving COVID-19 vaccinations. It is hard to imagine what our lives would be like without this small but essential tool. We can thank 19th century physicians for embracing what to them was a new technology and laying the foundation for more widespread use in the future.

About the Author

Kyle Dalton is a summa cum laude graduate of the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, where his paper Active and Efficient: Veterans and the Success of the United States Ambulance Corps was awarded the Zeender Prize for best history thesis. He was previously on the staff of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine and is now Executive Director at Union Mills Homestead historic site. In his spare time Kyle writes and maintains a website on the lives of common sailors in the eighteenth-century: BritishTars.com.

Sources

[1] Jones, Jonathan S., “Then and Now: How Civil War Era Doctors Responded to Their Own Opiate Epidemic,” November 3, 2017.

[2] Rynd, Francis, “Neuralgia – Introduction of Fluid to the Nerve,” The Dublin Medical Press, A Weekly Journal of Medicine and Medical Affairs, Vol. XIII, From January to June, Inclusive, Dublin: Medical Press Office, 1845, page 167.

[3] Will, Elizabeth M., Brian M. Will, Michael J. Will, and Alia Koch, “Minimally Invasive Cosmetic Procedures,” in The History of Maxillofacial Surgery: An Evidence-Based Journey, Springer: e-book, 2022, 426, via Google Books, accessed October 31, 2022, <https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_History_of_Maxillofacial_Surgery/Kc5kEAAAQBAJ>.

[4] Smith, Stephen, M.D., The Hand-Book of Surgical Operations, second edition, New York: Bailliere Brothers, 1862, pages 90-91, via U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections, accessed October 28, 2022, < https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101561622-bk >.

[5] “Hypodermic,” via Meriam-Webster, accessed October 31, 2022, <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hypodermic>.

[6] Lewy, Jonathan, “The Army Disease: Drug Addiction and the Civil War,” War in History, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 102-119, via JSTOR, accessed January 29, 2020, <https://www.jstor.org/stable/26098368>.

[7] The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, Page 547, Part III, Volume I, via HathiTrust Digital Library, accessed November 7, 2022, <https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo1.ark:/13960/t6c263n0k&view=1up&seq=612&q1=hypodermic>.

[8] Medical and Surgical History, Part III, Volume II, second issue, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1883, pages 9, 36, and 811, via HathiTrust Digital Library, accessed November 7, 2022, <https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t3zs2kk2m&view=1up&seq=905&q1=hypodermic>. Notably every case was in the Eastern Theater, with two out of the three cases in Washington, DC hospitals. An additional case is included in this volume at the far-flung outpost of Fort Union, New Mexico in 1867 on page 150.

[9] Courtwright, David T., “Opiate Addiction as a Consequence of the Civil War,” in The Civil War Veteran: A Historical Reader, Larry M. Logue and Michael Barton editors, New York: New York University Press, 2007, page 106.

[10] “Post-War Speech by Civil War Surgeon W.W. Keen on Military Surgery,” November 3, 1918, via National Museum of Civil War Medicine, accessed October 31, 2022, <https://civilwarmed.321staging.com/keen-surgery/>.

[11] Aker, Janet A., “’America’s First Brain Surgeon’ Served During Civil War and World War I,” via the Military Health System, accessed October 31, 2022, < https://www.health.mil/News/Articles/2022/05/17/Americas-First-Brain-Surgeon-Served-During-Civil-War-and-World-War-I?page=3#pagingAnchor >.

[12] Mitchell, S. Weir, M.D., Wm. W. Keen, M.D., and George R, Morehouse, M.D., “On the Antagonism of Atropia and Morphia, Founded upon Observations and Experiments made at the U.S.A. Hospital for Injuries and Diseases of the Nervous System,” in The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, No. WCIX New Series, July 1865, pages 67-76, via the Smithsonian Libraries, accessed October 28, 2022, <https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/americanjourna501865thor>.

[13] “The Hypodermic Syringe. First Used in the Confederate States Army,” Southern Historical Society Papers, Volume 31,Reverend J. William Jones editor, via Tufts University, accessed October 31, 2022, <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0289%3Achapter%3D1.54>.

[14] Mitchell et al., “On the Antagonism,” page 68.

[15] White, William L, “The Hypodermic Syringe and the Rise of Addiction,” William White Papers, 2014, via Chestnut Health Systems, accessed October 28, 2022, <https://www.chestnut.org/william-white-papers/114/addiction-history-briefs/items/>.

[16] https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t3zs2kk2m&view=1up&seq=933&q1=hypodermic

[17] Campbell, Henry Fraser, M.D., “Article XI. Caffeine as an Antidote in the Poisonous Narcotism of Opium,” in Southern Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol. XVI, No. 5, Augusta, Georgia, May 1860, page 238, via Augusta University, accessed April 13, 2022, <https://augusta.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10675.2/920/SMSJ.1860.issue5.pp.321-400.pdf?sequence=20&isAllowed=y>.

[18] Michell, M.D., S. Weir, “Characteristics,” in The Century Illustrated Magazine, Vol. XLIII, New Series: Vol. XXI, The Century Co., 1892, page 290, via Google Books, accessed November 7, 2022, <https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Century_Illustrated_Monthly_Magazine/fWoiAQAAIAAJ>.