Table of Contents

Then raise the harp of Erin, boys, the flag we all revere

We’ll fight and fall beneath its folds, like Irish volunteers!

–The Irish Volunteer, David Kincaid

When the Civil War was in its earliest stages, one of the first regiments to be brought into service was the 69th New York Infantry, an all-Irish militia. The first commander of the regiment was Colonel Michael Corcoran, a native Irishman who enlisted in the New York Militia as a private and rose up the ranks to Colonel before the outbreak of the Civil War. The 69th NY Infantry soon became known as the Irish Brigade and was joined by the 63rd and 88th New York Infantry regiments, also comprised of a majority of Irish immigrants and Irish-Americans. Only several thousand of the nearly 200,000 Irish-American soldiers who served in the Union Army were members of ethnic regiments like the Irish Brigade. 7,715 men served in the brigade, 961 were killed or mortally wounded and around 3,000 were wounded. The exceptionally high casualty rate makes taking a closer look at this storied unit well worth it.[1]

The Irish Brigade served in every major battle in the Eastern Theater throughout the Civil War, taking heavy casualties along the way. By the end of the Civil War, eleven members received the Medal of Honor, and the brigade suffered the 3rd highest number of battlefield casualties in the Union Army. Other notable brigades with high casualty rates during their service include the Iron Brigade and the First Vermont Brigade.

Before the outbreak of the Civil War, Col. Corcoran was in the middle of a court martial for insubordination for refusing to march his men through New York City for a visit by the Prince of Wales in 1860. In the middle of the trial, Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter and Corcoran’s charges were dropped. The 69th New York made its way down to Washington, DC to begin their service and marched towards Manassas Junction along Bull Run. On that day in July 1861, Col. Corcoran led the “Fighting 69th” to Henry House Hill where they engaged in a fierce battle with Confederate forces. Col. Corcoran became injured during their retreat and was captured by the Confederates. Even still, the 69th held steady, protecting the rear of the Union lines while the rest of the Union army was retreating.[2]

After the Battle of First Bull Run, the War Department authorized lawyer, orator, and Irish revolutionary Captain Thomas Francis Meagher (pronounced “mar”) of Company K, 69th NY, to recruit more Irish immigrants and Irish-Americans, creating the Irish Brigade as part of Brigadier General Edwin Sumner’s II Corps.[3] Brigadier General Meagher raised the 63rd and the 88th New York Infantry to join the 69th New York in the formation of the Irish Brigade with the motto Riamh nár dhruid ó spairn lann, which translates to “Who never retreated from the clash of spears.”

The Irish Brigade’s first major engagement was during the Peninsula Campaign from May to June, 1862. During the Battle of Fair Oaks, the Irish Brigade rushed to the railroad line while under fire from Armistead’s Confederates and reinforcing French’s Division. The three regiments of the Irish Brigade held the line and “the enemy, although in considerable force and evidently bent on a desperate advance, were compelled to retire, leaving their dead and wounded piled in the woods and swampy ground in front of our line of battle.”[4] The Irish Brigade and other Union units succeeded in pushing back the Confederates and only suffered 39 casualties according to Meagher’s report.

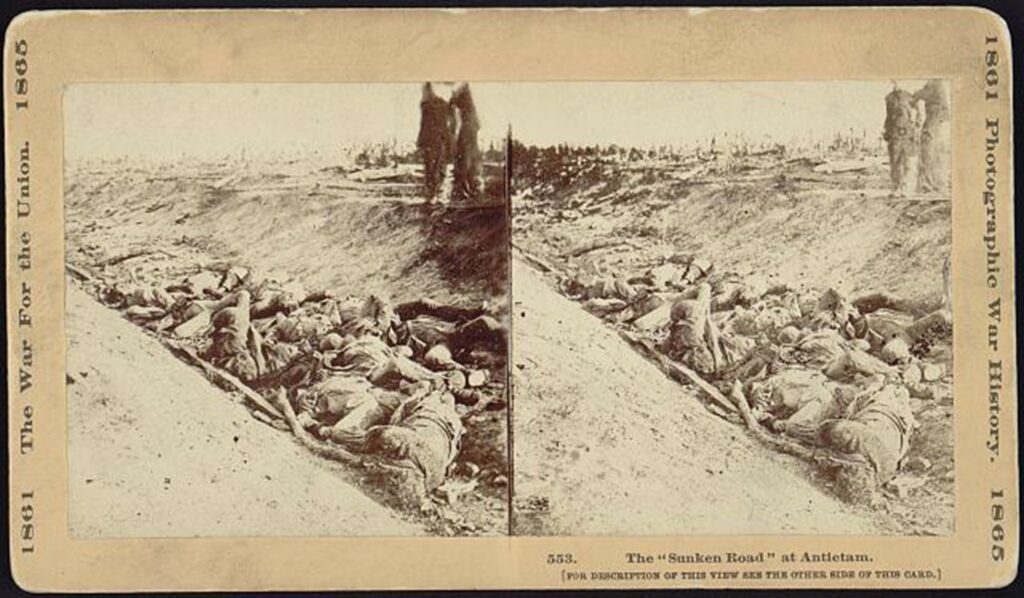

Several months later, in September of 1862, the 29th Massachusetts was added to the Irish Brigade. During the Battle of Antietam on September 17, the Irish Brigade marched through a field of corn, followed by their chaplain, Father William Corby, who gave them absolution while going into battle. “In twenty or thirty minutes after this absolution, 506 of these very men lay on the field, either dead or seriously wounded.”[5] The regiment crossed a rail fence before pouring volleys into the Confederates from 300 paces. The brigade continued its advance and charged with fixed bayonets, running straight into Confederate General George B. Anderson’s North Carolinians. The Confederates retreated to the sunken road, continuously pursued by the Irish Brigade until they were driven out of the “Bloody Lane” and the brigade ran out of ammunition. For their brave assault on that Confederate position, the Irish brigade suffered 60% casualties with Brigadier General Meagher becoming wounded as well.[6]

One soldier wounded at Antietam was Private Michael B. Horan, Co. F, 63rd NY. Private Horan suffered from a gunshot wound to the right tibia and knee. He was taken to the Pry House Field Hospital before being moved to General Hospital #5 in Frederick, MD which was the Visitation Academy and Novitiate. Horan received a “partial resection of the knee joint… for a shot injury of the condyles of the femur…”[7] Thirteen fragments of bone were extracted from his knee on October 4, his condition deteriorated, and Private Horan died on October 14. He is buried at the Antietam National Cemetery in grave #271.

Just three months after the bloodiest day in American history, the Irish Brigade was back with the Army of the Potomac, joined by the 116th Pennsylvania and the 28th Massachusetts, replacing the 29th. Brigadier General Meagher returned from his injury in time for the Battle of Fredericksburg in December of 1862. After crossing the Rappahannock River into the city of Fredericksburg, General Ambrose Burnside and the Union army began to clear the city before advancing on Marye’s Heights which overlooked Fredericksburg.

General Meagher was informed that he would be leading his men as part of the fifth assault to take the hill, and as it turned out, his Irish Brigade would be charging up the hill opposite to the 24th Georgia, a Confederate regiment of Irish immigrants. Meagher’s Irish Brigade advanced up the hill, taking heavy fire from muskets and artillery before being forced to retreat back to their lines. The brigade lost 14 officers, and 512 of the 1000 men they arrived at Fredericksburg with.[8]

Private William McCarter, a 21-year-old Irish immigrant originally mustered in the 116th Pennsylvania. He had impressed Brigadier General Meagher with his handwriting and was transferred as a clerk to his headquarters. However, McCarter would see combat during the assault on Marye’s Heights. According to one account that describes the wounds suffered by Private McCarter, “one spent ball struck McCarter on the left shoulder, giving him a large bruise; another clipped his ankle, inflicting a painful, if not dangerous, wound. A Minieball pierced the cartridge box at his side, while others cut through his uniform.”[9] Private McCarter collapsed after suffering another wound to his arm and fell where he stood. Using the body of a fallen comrade, he was able to take cover from incoming Confederate fire until later that night. Men from his own regiment found him while searching for wounded men and evacuated him to an awaiting ambulance for treatment. During the evacuation of Fredericksburg, and after several hours of waiting, McCarter was evacuated and sent to recover in a Washington hospital. Private William McCarter was discharged five months later after suffering permanent damage to his arm.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Irish Brigade had prided itself on not losing any of its colors, both national and regimental, to that point. However, the men of the 69th could not find their national colors and feared the worst, prompting them to return to the field in search of their color bearer. After some time searching, they found the sergeant against a tree with an empty flagstaff next to his body. Upon searching the man, they discovered the flag wrapped around his body under his coat to protect it from capture. He had been shot through the heart protecting the nation’s flag.[10]

After the Battle of Chancellorsville, which the Irish Brigade was lightly engaged in, Brigadier General Meagher resigned his command after the Union would not allow him to recruit more men for the brigade. Before the Battle of Gettysburg, Colonel Patrick Kelly took command of the brigade until his death during the Siege of Petersburg. From almost 4,000 men to only a few hundred within two years, the Brigade would never return to its full strength, but that did not deter the Irish Brigade from earning its reputation as a one of the most famed regiments of the Civil War. Despite its overall strength of only 330 men, almost all of the men from the 69th, 63rd, 88th NY, 116th PA, and 28th MA reenlisted when their terms of service expired in 1864.[11] While present at Appomattox during Robert E. Lee’s surrender, the Irish Brigade was the size of a regiment and had been redistributed into parts of the 3rd and 4th brigades of 1st Division’s II Corps. The 69th New York would be reestablished shortly after the war as part of the state militia force later becoming the National Guard of the same designation.

The brigade always happened to be right in the thick of the fighting, waving their regimental flag bearing a golden harp on a green background with pride and living up to the motto on the colors and their battle cry Faugh A Ballagh which translates to “Clear the way!” The Irish Brigade remains one of the most recognizable units to serve in the Civil War. During World War 1, the 69th New York was redesignated as the 165th Infantry regiment of the 42nd Division, nicknamed the “Rainbow Division.” The regiment again became active during World War 2, primarily serving in the Pacific Theater with the 27th Infantry Division. Today, the legacy of the Irish Brigade lives on in the 1st Battalion 69th Infantry of the New York National Guard who served with distinction in Iraq and the ongoing War on Terror.

May Erin’s Harp and the Starry Flag united ever be;

May traitors quake, and rebels shake, and tremble in their fears,

When next they meet the Yankee boys and Irish volunteers!

God bless the name of Washington! that name this land reveres;

Success to Meagher and Nugent, and their Irish volunteers!

-The Irish Volunteer, David Kincaid

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021. He is currently pursuing a Masters in American History from Gettysburg College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute.

Sources

[1] Searles, Harry. “Irish Brigade.” American History Central. R. Squared Communications, LLC, April 20, 2022. https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/irish-brigade/.

[2] “The Men Who Led the 69th New York on the Bull Run Battlefield.” Irish in the American Civil War, March 23, 2020. https://irishamericancivilwar.com/2019/04/09/the-men-who-led-the-69th-new-york-on-the-bull-run-battlefield/.

[3] Searles, Harry. “Irish Brigade.” American History Central. R. Squared Communications, LLC, April 20, 2022. https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/irish-brigade/.

[4] Meagher, Thomas F. “Report of Brigadier General Thomas F. Meagher, U.S. Army, Commanding Second Brigade.” The Irish Brigade at the Battle of Fair Oaks (or Seven pines), n.d. https://history.army.mil/html/topics/ethnic/irish/fairoaks.html.

[5] Corby, William. Memoirs of Chaplain Life. Bethesda, MD: University Publications of America, 1992. Pg 112.

[6] Battle of Antietam, n.d. https://irishworkhistory.omeka.net/exhibits/show/irish-in-the-civil-war/battle-of-antietam.

[7] “The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion,” Part III, Vol. II pg. 392.

[8] McGinley, John. “The Clash of the Irish Brigades at the Battle of Fredericksburg.” IrishCentral.com, January 13, 2022. https://www.irishcentral.com/opinion/others/clash-irish-brigades-battle-of-fredericksburg.

[9] Pfanz, Donald. “One Man’s Ordeal: William McCarter.” Fredericksburg.com, April 11, 2019. https://fredericksburg.com/one-mans-ordeal-william-mccarter/article_28387df7-899d-5606-bbec-1cdc478f85d0.html.

[10] Jones, Terry L. “The Fighting Irish Brigade.” The New York Times. The New York Times, December 11, 2012. https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/12/11/the-fighting-irish-brigade/.

[11] Craughwell, Thomas. “The Irish Brigade – Essential Civil War Curriculum,” n.d. https://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/the-irish-brigade.html.