Dr. Foster (played by Josh Radnor) must have found time to keep up with his medical journals and bulletins! Foster observes “cardiac palpitations” in Tom (Cameron Monaghan) and diagnoses him with “soldier’s heart,” a brand new diagnosis just identified by Philadelphia physician Jacob M. Da Costa.

In 1862, this would have been a very new diagnosis. It’s unsurprising that, later in the episode, Foster’s supervisor questions both the diagnosis and Foster’s treatment program. Only the most informed surgeons would have been aware of Da Costa’s work and the letter he sent to the Surgeon General’s office about the new, “peculiar functional disorder of the heart.”

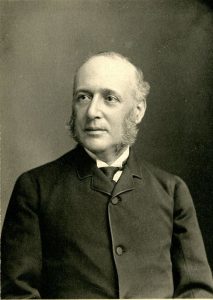

Dr. Da Costa was a real physician working as an Acting Assistant Surgeon (essentially a civilian contract surgeon, Dr. Foster’s position) in Philadelphia. Over the course of the war, Da Costa studied over 300 soldiers who complained of chest pain, a very rapid pulse (one patient registered a pulse of 192 beats per minute!), irregular heartbeats, difficulty breathing, tunnel vision, fatigue and weakness, bad dreams, difficulty sleeping, headaches and more. Not every patient experienced all of these symptoms, but all irritable heart patients would present at least a rapid pulse, heart palpitations, and chest pain, often following some kind of digestive disturbance. Da Costa noted that nervous symptoms, like bad dreams or headaches, were characteristic but less universal than the cardiac symptoms.

Unlike Mercy Street’s Dr. Foster, Da Costa called this heart condition irritable heart– “soldier’s heart” is a more poetic phrase that hints at the emotional trauma that Tom suffered but that term did not come into use as a name for this condition until well after the Civil War. During the 1860s and 1870s, most physicians would have referred to the condition as either irritable heart or Da Costa’s Syndrome.

Unlike Mercy Street’s Dr. Foster, Da Costa called this heart condition irritable heart– “soldier’s heart” is a more poetic phrase that hints at the emotional trauma that Tom suffered but that term did not come into use as a name for this condition until well after the Civil War. During the 1860s and 1870s, most physicians would have referred to the condition as either irritable heart or Da Costa’s Syndrome.

The show’s writers use irritable heart as a kind of shorthand for what we might today call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). My research suggests that it is not entirely accurate to equate irritable heart with PTSD because PTSD is, like irritable heart, the discovery of physicians working at a specific moment in time with particular tools, techniques, and insights at their disposal. It’s easy to understand why Mercy Street’s writers made this connection. The symptoms for irritable heart sound a lot like a panic attack but, while Dr. Foster says that that the cardiac symptoms are “precipitated by battle trauma,” Da Costa was much less sure on this score. In his writing on the condition, men were as likely to come down with irritable heart after “digestive disturbances” (an attack of diarrhea) as they were when faced with excessive marching or the “excitement of battle.”

Nineteenth century physicians did not have a concept of psychological trauma the way that we do today. During the Civil War, few if any American physicians took a psychological view of either the “disturbed” or the sick. Freud hadn’t even begun his work on the subconscious when Da Costa was studying his patients in Pennsylvania. If irritable heart is not a Civil War era version of PTSD, we might call it a “conversion disorder,” where someone experiences physical pain as a result of psychological distress. Even this classification relies on advances in the fields of psychiatry and neurology advanced. While “the excitement of battle” might include emotions like fear, when Da Costa talked about nervous energy he meant the over-taxing of the nervous system, not the emotions of his patient.

This is not to say that Tom is emotionally or physically healthy. Without a doubt, the Civil War broke men; they suffered from severe physical deprivations, witnessed death on a scale previously unimaginable, and deeply missed their families and homes. Da Costa never doubted his patients’ pain or the reality of their suffering. However, he never assumed that men who suffered from irritable heart were, by definition, traumatized by their battlefield experience. A few years after the war, some military physicians, former Surgeon General Hammond among them, began to look into possible cardiac causes of insanity. Even when leading military doctors turned to the heart’s role in insanity, they stopped short of a kind of emotional explanation for what they observed.

Dr. Foster treats Tom by injecting him with morphine. Da Costa found that opiates could help patients by reducing their heart rate and easing their pain (perhaps not a huge surprise) but he was hesitant to use this treatment out of fear of turning the man into “an opium eater.” Instead, he suggested treating irritable heart patients with rest, light exercise, and tincture of aconite.

About the Author

Ashley Bowen received her PhD candidate in American Studies at Brown University. Her dissertation is titled “‘All Broke Down:’ The Physiological, Psychological, and Social Origins of Civil War Trauma.” Prior to entering graduate school, she worked for a variety of museums and public health organizations.

Works Consulted

Chamberlain, Joshua Lawrence, ed. “Da Costa, Jacob Mendes, 1833-1900: Trustee 1899-1900.” In University of Pennsylvania: Its History, Influence, Equipment and Characteristics; with Biographical Sketches and Portraits of Founders, Benefactors, Officers and Alumni, 1:477–78. Boston: R. Herndon Company, 1901.

Clarke, Mary A. “Memoir of J.M. Da Costa, MD.” Journal of the Medical Sciences 125, no. 2 (February 1903): 318–29.

Da Costa, JM. Medical Diagnosis with Special Reference to Practical Medicine: Guide to the Knowledge and Discrimination of Diseases. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co, 1864.

———. “Observations on the Diseases of the Heart Noticed among Soldiers, Particularly the Organic Diseases.” In Contributions Relating to the Causation and Prevention of Disease, and to Camp Diseases; Together with a Report of the Diseases, Etc., Among the Prisoners at Andersonville, GA, edited by Austin Flint, 360–82. New York: United States Sanitary Commission by Hurd and Houghton, 1867.

———. “On Irritable Heart: A Clinical Study of a Form of Functional Cardiac Disorder and Its Consequences.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 61, no. 121 (January 1871): 17–52.

Hammond, William Alexander. A Treatise on Insanity in Its Medical Relations. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1883.

Wooley, C. F. “Where Are the Diseases of Yesteryear? Da Costa’s Syndrome, Soldiers Heart, the Effort Syndrome, Neurocirculatory Asthenia–and the Mitral Valve Prolapse Syndrome.” Circulation 53, no. 5 (May 1, 1976): 749–51. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.53.5.749.

Wooley, Charles F. “From Irritable Heart to Mitral Valve Prolapse: The Osler Connection.” The American Journal of Cardiology 53, no. 6 (March 1, 1984): 870–74. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(84)90422-3.

———. “Jacob Mendez Da Costa: Medical Teacher, Clinician, and Clinical Investigator.” The American Journal of Cardiology 50, no. 5 (November 1982): 1145–48. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(82)90434-9.

———. The Irritable Heart of Soldiers and the Origins of Anglo-American Cardiology: The US Civil War (1861) to World War I (1918). The History of Medicine in Context. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2002.

Zederbaum, A. “Mental Disturbances in the Course of Cardiac Disease.” Transactions of the Colorado State Medical Society, 1901, 222–33.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.