Table of Contents

Although many Civil War soldiers were conscripted into service, most enlisted with the help of Army recruiters.[1] When we think of Army recruiters, we often envision stationary recruiting offices filled with men speaking to other men imploring them to enlist. But this is an incomplete image. This is the story of Mary Ann Shadd Cary, an African American female recruiter.

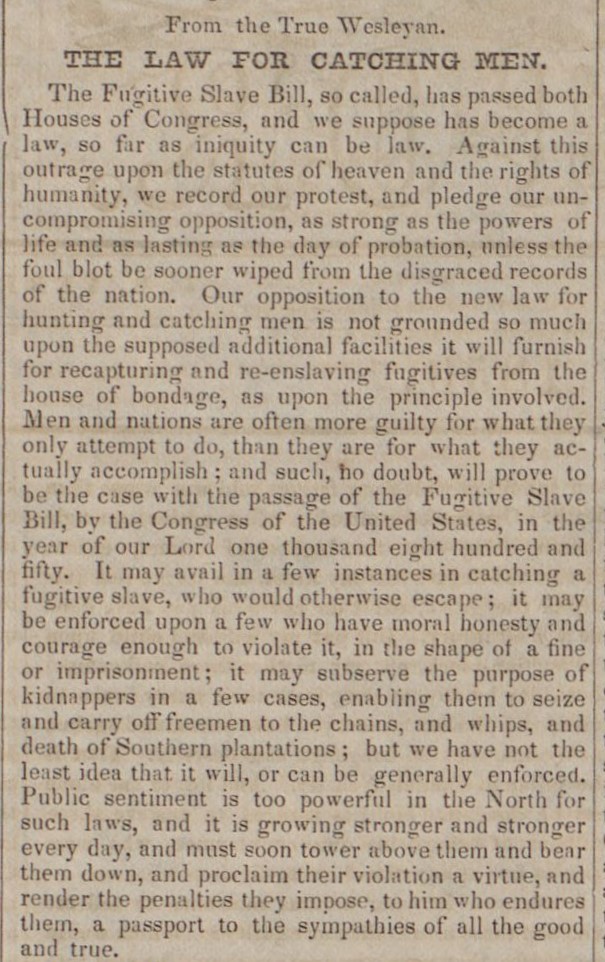

Mary Ann Shadd Cary was born free in Wilmington, Delaware on October 9, 1823.[2] She lived in Delaware and Pennsylvania, received an education, and became a teacher in the United States.[3] Her life, like the lives of many free African Americans, changed dramatically in 1850 when Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, threatening the lives of all African Americans residing in the North.[4] To preserve her freedom and in search of a better life, Shadd Cary emigrated to Canada where she became North America’s first Black female newspaper editor with her newspaper, The Provincial Freeman.[5] In print from 1853 to 1857, the paper featured lively discussions about abolition, women’s rights, and racial integration, while encouraging African Americans to emigrate to Canada.

Shadd Cary’s support for Black emigration to Canada was based on her belief that Canada provided more freedoms and harbored less prejudice towards Black people than the United States.[6] During the first few years of the Civil War, she remained a staunch advocate of Black emigration to Canada believing that the war would not yield any positive changes for African Americans.[7] However, the passage of the 1862 Militia Act and the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, which opened the door for Black men to enlist in the Union Army, ignited hope that African Americans could live fruitful lives in the United States.[8]

While some states quickly began forming Black regiments including the famous 54th Massachusetts, other states, such as Connecticut, delayed. After consistent urging by Colonel Dexter R. Wright and Colonel Benjamin S. Pardee to form Black regiments, the Connecticut General Assembly approved a bill to raise troops for the 29th Connecticut Colored Infantry on November 23, 1863.[9] Recruiters quickly stepped up to fill the regiment.

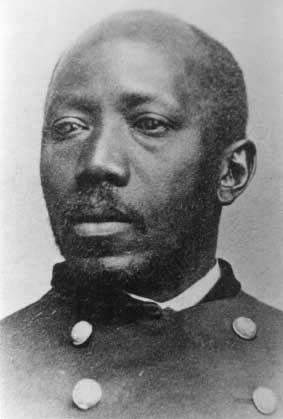

Against this backdrop, Shadd Cary received a letter from a longtime friend and fellow abolitionist, Martin R. Delany, on December 7, 1863. Delany was working as a Union Army recruiter for the newly forming Black regiments and hoped to hire more recruiting agents. Delany thought of Shadd Cary and asked her to return to the United States to begin recruiting Black men for the Union Army.[10] Shadd Cary accepted the job and journeyed back to America.

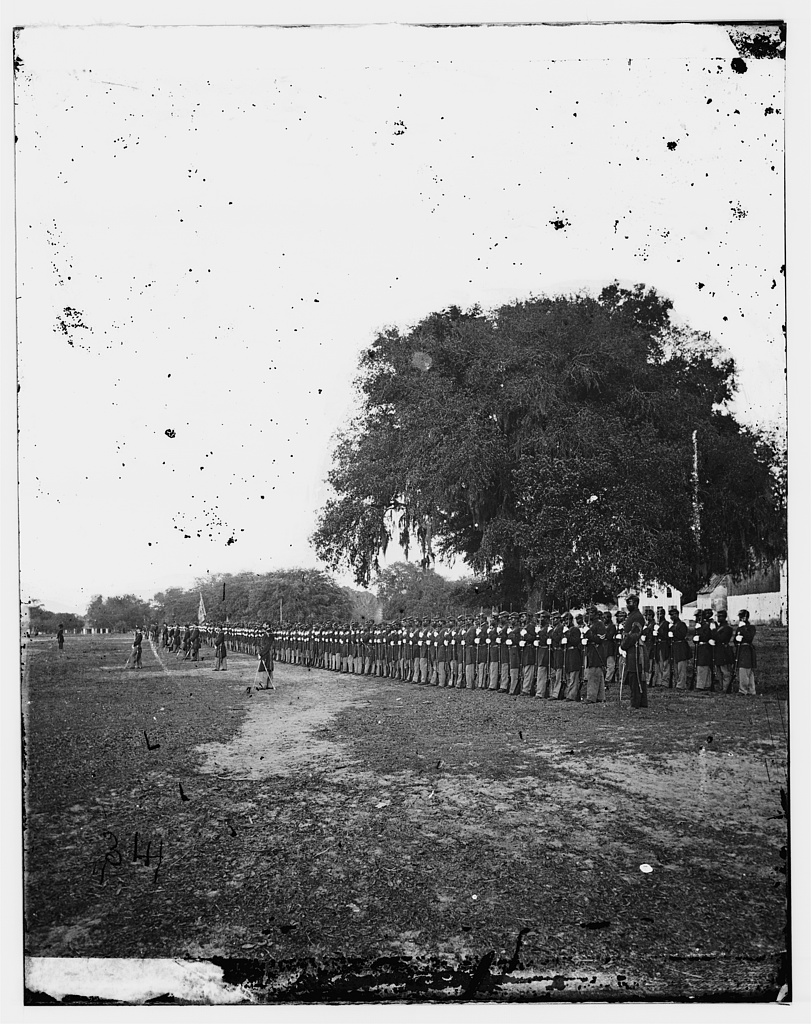

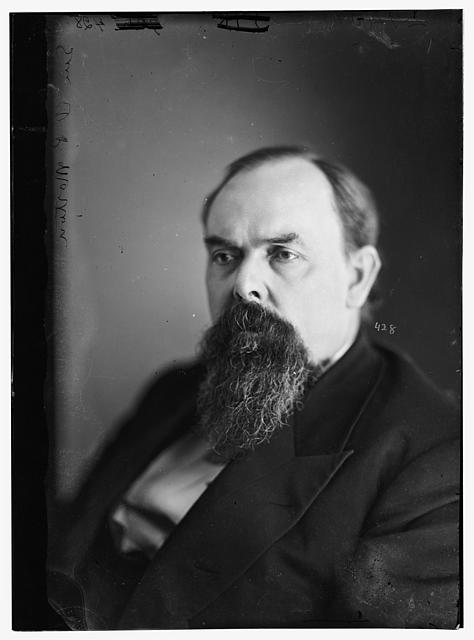

Upon arriving in the United States, Mary Ann Shadd Cary joined Delany in recruiting for the 29th Connecticut Colored Infantry. Shadd Cary traveled throughout the midwest to recruit men for this regiment.[11] Her travel throughout the midwest to recruit men for a northeastern regiment was not unusual as many recruiters traveled broadly to fill regimental quotas. On February 19, 1864, Shadd Cary received a letter from the Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton proclaiming that she was “entitled to protection in transit through [Indiana] with recruits.”[12] Five days later, she received a letter from Colonel Benjamin S. Pardee, the Commander of Recruiting Services in Connecticut, saying she was “authorized and empowered as my agent to obtain men.”[13] Armed with these guarantors of her authority, Shadd Cary along with other recruiters enlisted enough troops to form the 29th Connecticut Colored Infantry. This regiment was mustered on March 8, 1864 meaning the recruiters successfully enlisted at least 1,000 men within 3 months of the General Assembly approving the formation of a Connecticut Black regiment.[14]

These recruiters were so successful that they had raised an additional few hundred troops which were used to form the beginnings of the 30th Connecticut Colored Infantry.[15] Needing to fill this second regiment, Colonel Pardee wrote to Mary Ann Shadd Cary again on March 3, 1864 promising to “reward [Shadd Cary] handsomely, besides [her] regular pay” if she was successful in encouraging men to enlist.[16] Ultimately, the 30th Connecticut Colored Infantry never became its own regiment. Instead, it was incorporated into the 31st United States Colored Infantry on May 18, 1864.[17] This regiment would be present at the Battle of Appomattox Courthouse.[18]

As the war progressed, Mary Ann Shadd Cary continued recruiting. Most notably, on August 15, 1864, Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton and Adjutant General Lazarus Noble officially appointed Shadd Cary as a “Recruiting Officer” to enlist “Colored Volunteers in any County…under the call for 500,000 men, issued July 17, 1864.”[19] Shadd Cary’s Indiana efforts likely culminated in recruiting troops to reinforce the 28th U.S. Colored Infantry.

The 28th U.S. Colored Infantry was first mustered in April of 1864, about four months before Shadd Cary was officially appointed a recruiting officer.[20] The men of this regiment quickly faced great adversity when they fought in the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864, losing 88 men (11 killed, 64 wounded, and 13 missing).[21] Shadd Cary was officially appointed a recruiting officer two weeks later. The July 30th losses, combined with the earlier July 17th call for more volunteers, likely generated enough urgency to make the Indiana government willing to officially appoint Shadd Cary as a recruiting officer, despite her sex.

While recruiting men for the Indiana regiment, Shadd Cary filled what little free time she had with other duties. She sought donations for the Mission School, a racially integrated Canadian school that herself and Amelia Freeman Shadd, her sister, operated.[22] She also worked as a traveling agent collecting donations for the Colored Ladies Freedmen’s Aid Society.[23]

By late 1864, Shadd Cary completed her recruiting duties and returned to Canada where she lived until the Civil War concluded.[24] She would later move to Washington D.C. where she served as a principal for three schools and eventually earned a law degree from Howard University.[25]

Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s career as an Army recruiter is incredibly unique on account of her sex. Although historians believe women such as Sojourner Truth and Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin encouraged Black men to enlist, to be formally appointed as a recruiting officer and paid for that work was a unique position for a woman.[26] The uniqueness of Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s story does not make her role as an Army recruiter any less important. Uncovering stories like these are how we, as historians, can create a more accurate image of American history.

About the Author

Gabrielle McCoy earned her BA in History from the University of Maryland. She is currently studying at the University of South Carolina to earn a Master’s in public history and a PhD in history. Her research focuses on nineteenth-century masculine performance in the American South.

Endnotes:

[1] The Confederacy began conscription on April 16, 1862 and the Union began conscription on March 3, 1863.

[2] Martha Jones, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, And Insisted On Equality For All (New York: Basic Books, 2020), 73.

[3] Carol B. Conaway, “Racially Integrated Education: The Antebellum Thought of Mary Ann Shadd Cary and Frederick Douglass,” in Life Stories: Exploring Issues in Educational History through Biography, ed. Linda C. Morice (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, 2014), 4; Carla L. Peterson, “Doers of the Word”: African-American Women Speakers and Writers in the North (1830-1880) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 98.

[4] Gabrielle McCoy, “Speech to Judiciary Committee re: The Rights of Women, (January 1872) Washington, D.C.: Context,” Recovering Democracy Archives, Last accessed May 26, 2022, https://recoveringdemocracyarchives.umd. edu/rda-context/?ID=2309.

[5] Rinaldo Walcott, “‘Who is She and What is She to You?’: Mary Ann Shadd Cary and the (Im)possibility of Black/Canadian Studies,” Atlantis 24, no. 2 (Spring/Summer 2000): 138, https://journals.msvu.ca/index.php/ atlantis/article/view/1598.

[6] Mary Ann Shadd Cary, A Plea for Emigration; Or, Notes of Canada West in its Moral, Social, and Political Aspect: With Suggestions Respecting Mexico, West Indies, and Vancouver’s Island for the Information of Colored Emigrants (Detroit, MI: George W. Pattison, 1852).

[7] Jane Rhodes, Mary Ann Shadd Cary: The Black Press and Protest in the Nineteenth Century (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1998), 151; Mary Ann Shadd Cary was not the only African American to believe the Civil War would not positively alter the position of African Americans. To learn more about Civil War conversations regarding Black military service and the potential costs and benefits for African American citizenship, see: Brian Taylor, Fighting for Citizenship: Black Northerners and the Debate over Military Service in the Civil War (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2020).

[8] Rhodes, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, 151.

[9] William Augustus Croffut and John M. Morris, The military and civil history of Connecticut during the war of 1861-65: comprising a detailed account of the various regiments and batteries, through march, encampment, bivouac, and battle, also instances of distinguished personal gallantry, and biographical sketches of many heroic soldiers, together with a record of the patriotic action of citizens at home, and of the liberal support furnished by the state in its executive and legislative departments, (New York, NY: Ledyard Bill, 1868), 460, https://archive.org/det ails/militarycivilhis00lccrof/mode/2up.

[10] Rhodes, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, 153.

[11] Rhodes, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, 152.

[12] Martin R. Delany to Mary Ann Shadd Cary, February 19, 1864, Correspondence, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, https://dh.howard.edu/mscary_corres/4.

[13] Rhodes, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, 157; Mary Ann Shadd Cary authorization to obtain men for Connecticut volunteers, February 24, 1864, Certificates and Statements, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, https://dh.howard.edu/mscary_certs/5; Prior to Colonel Pardee’s position in the Connecticut Recruiting Office, he served with the 10th Regiment Infantry first as a Captain (September 21, 1862 to April 1, 1862), then as a Major (April 1, 1862 to June 5, 1862), and then as a Lieutenant Colonel (June 5, 1862 to September 7, 1862). Upon resigning, he appears to have gone straight to work in the Connecticut Recruiting Office wherein he was promoted to Colonel sometime before November 1863. See: Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of Connecticut, for the year ending March 31, 1866 (Hartford, CT: A.N. Clark & Co. State Printers, 1866).

[14] William Augustus Croffut and John M. Morris, The military and civil history of Connecticut during the war of 1861-65, 461.

[15] “November 23rd: Connecticut’s First African-American Civil War Regiment,” Today in Connecticut History, Office of the State Historian, Last updated November 23, 2021, https://todayincthistory.com/2021/11/23/november -23-connecticuts-first-african-american-civil-war-regiment-4/.

[16] Benjamin S. Pardee to Mary Ann Shadd Cary, March 3, 1864, Correspondence, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, https://dh.howard.edu/mscary_corres/7.

[17] “31st Infantry, US Colored Troops,” New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, Last accessed May 26, 2022, https://museum.dmna.ny.gov/unit-history/civil-war-colored-troops/infantry/31st-inf antry-us-colored-troops.

[18] “United States Colored Troops at Appomattox,” National Park Service, Last updated September 6, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/apco/learn/historyculture/united-states-colored-troops-at-appomattox.htm#:~:text=General%20Grant%20brought%20elements%20of,troops%20of%20the%2025th%20Corps.

[19] Mary Ann Shadd Cary State of Indiana appointment as recruiting officer to enlist colored volunteers, August 15, 1864, Certificates and Statements, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, https://dh.howard.edu /mscary_certs/1.

[20] Indiana Historical Bureau State of Indiana, “Indiana’s 28th Regiment: Black Soldiers for the Union,” The Indiana Historian, 5, https://www.in.gov/history/files/7023.pdf.

[21] Indiana Historical Bureau State of Indiana, “Indiana’s 28th Regiment: Black Soldiers for the Union,” The Indiana Historian, 10,https://www.in.gov/history/files/7023.pdf; William F. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1861-1865: A treatise on the extent and nature of the mortuary losses in the Union regiments, with full and exhaustive statistics compiled from the official records on file in the state military bureaus and at Washington (Albany, NY: Albany Publishing Company, 1889), 55.

[22] Rhodes, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, 150.

[23] Rhodes, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, 157.

[24] Rhodes, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, 158.

[25] Shirley J. Yee, “Finding a Place: Mary Ann Shadd Cary and the Dilemmas of Black Migration to Canada, 1850-1870,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 18, no. 3 (1997): 11, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3347171; Jason H. Silverman, “Mary Ann Shadd and the Search for Equality” in Black Leaders of the Nineteenth Century, eds. Leon Litwack and August Meier (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 97-98; Rhodes, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, 186; S.C. Evans, “Mrs. Mary Ann Shadd Cary,” in Homespun Heroines and Other Women of Distinction, ed. Hallie Quinn Brown (Xenia, OH: Aldine Printing House, 1926), 95.

[26] Rhodes, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, 155.