Table of Contents

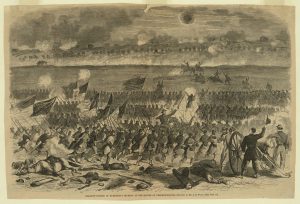

William McCarter had a relatively short American Civil War experience. He enlisted with the Union Army’s 116th Pennsylvania Infantry in August 1862. Within five months he received severe wounds at the Battle of Fredericksburg resulting in the end of his service. McCarter’s story is often repeated in literature on the Irish American experience during the Civil War due to his service with the Union’s famed Irish Brigade. McCarter’s post-war memoir, My Life with the Irish Brigade, goes into extensive detail about the battle and the horror of being left on the field surrounded by dead and dying men. As he described it, “death, havoc, and carnage was visible at every step on the ground fronting Marye’s Heights.”[1]

McCarter was shot in his left shoulder and ankle, and more severely in his right arm around his shoulder and armpit, “inflicting a very serious wound” that rendered him unconscious.[2] The bullet that injured him scattered into seventeen parts: McCarter was fascinated by the “curious courses these little messengers of death took after entering the body.”[3] Lying wounded on the battlefield for hours, he watched subsequent failed Union assaults and avoided Confederate sharpshooter bullets before eventually struggling back into the town. Even when he wrote of his experiences over fifteen years later, McCarter realized he had a near-miraculous escape from death.[4]

McCarter’s story is certainly valuable in providing an eyewitness account of the events at Fredericksburg and Marye’s Heights on December 13, 1862, and in detailing life in the Irish Brigade at its peak regimental strength and fame. Often overlooked, however, are his memoir’s final sections detailing “Life in the Hospital” as he recuperated. For five months, from December 1862 through to May 1863 when he was discharged from hospital and army service, McCarter recorded his experiences as a patient of war. His account provides both a personal and broader insight into soldiers’ medical treatment and care.

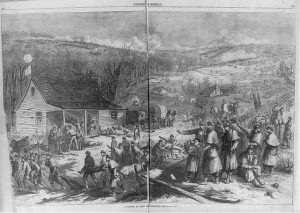

In the aftermath of Fredericksburg, as the wounded were transported away from the front, McCarter described his initial medical treatment and the atmosphere of tented military field hospitals. One particular aspect stuck in his mind: the presence of doctors, their surgical equipment and how it was being used. At one point he noted seeing “three army surgeons… from the appearance of their uniforms and the instruments they carried, I judged that they had seen hard service during the night in the line of their profession.”[5] McCarter was referring to amputation, a subject matter that played on his mind and reappears throughout the final passages of his wartime memoir. Further on, he recalled passing by tents “used for surgical operations.”

There were many amputations then going on… lying around were cases of ugly looking surgical tools, including the saw and knife. In the back end of each tent, a hole was made. Through it, amputated arms or legs were thrown out upon the ground.

Such a sight made McCarter deeply suspicious of amputation practices during the Civil War. To his mind “the amputations were very numerous and… in many cases entirely uncalled for.” He blamed young and inexperienced doctors for being too enthusiastic in removing limbs without giving the practice much thought. “These appendages could have been saved by proper care and the exercise of a little patience” he believed. In reality, amputation was often the only course of action for many Civil War injuries. The sooner one was amputated, the better their chance of survival. However, that did not make the idea any more pleasant.

McCarter was almost an amputee himself. During his preliminary treatment after Fredericksburg, one doctor came to him – holding “in one had a bloody knife or saw and in the other a newly amputated leg or arm dripping with human gore” – and asked if he wanted his arm removed as the shoulder injury was causing him great pain. McCarter declined and the doctor “turned away in disappointment” when he “refused to be a subject for his knife”[6]

One wonders whether McCarter ever regretted that decision as “for three weeks… my wound in my right arm refused to heal and became more painful. It gradually grew worse, causing me constant uneasiness and suffering,” particularly when he tried to sleep.[7] Even though care

and time paid off and McCarter received treatment for his wound, it never fully healed. At the very end of his memoir he noted that for several years after the war, bits of the bullet and broken bone “worked their way out of the wound at intervals of about one piece every three months”[8] Perhaps amputation would have spared him that.

McCarter’s arm was saved thanks to a fortuitous development in his personal patient care. During his time with the 116th Pennsylvania he had served as a secretary for the Irish Brigade’s commanding General Thomas Francis Meagher. When Meagher learned of McCarter’s ordeal and injury on Marye’s Heights, he had him transferred to the small Eckington Army Hospital by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad close to Washington D.C. Here McCarter was treated like an injured officer by a Dr. Edling of New York, “a gentleman in every sense of the term” who did not believe amputation was the best course of action.[9]

McCarter was well fed and looked after at Eckington, and far away from the bloody field hospitals he had previously experienced. The evenings sounded particularly restorative. He described spending them:

Smoking, seated on comfortable arm chairs around bright, cheerful fires… Our sources of evening amusements… included chess, cards, and dominoes. We were frequently entertained with beautiful and thrilling music on the clarinet, violin and its bass companion… often kept up until 11 to 11:30 at night.[10]

President Lincoln went to the hospital while McCarter was there, and he and his recovering soldiers “received many visits from the good ladies of Washington and its vicinity”[11] However, there was one group of ladies in particular that McCarter was most grateful for receiving attention from. He wrote fondly about the Catholic Sisters of Mercy who acted “as nurses… doing everything in their power to alleviate the terrible sufferings of the cargo of our wounded, sick and dying soldiers” as they were transported from Virginia’s battlefields to the capital. Breaking from his memoir’s narrative, McCarter explained how

I cannot proceed without paying my humble tribute of profound respect and praise to these women, ladies… their noble, heroic and unceasing exertions, many of them self-sacrificing in the extreme, were certainly wonderful and beautiful to witness. They did everything to ease the pain of the wounded, comforting and satisfying their cravings of the men.[12]

McCarter was lucky to survive the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862, but his injuries ended his time as a Union Army soldier. When he recalled his experience, it was clear that the aftermath of the battle, the sights of wartime hospitals and the careful treatment he received lived long in his memory. His account is a valuable source of study for exploring the nature of medicine and treatment during the Civil War.

Learn more about medical care at Fredericksburg with Director of Interpretation Jake Wynn

Footnotes

[1] My Life in the Irish Brigade: The Civil War Memoirs of Private William McCarter, 116th Pennsylvania Infantry, ed. Kevin E. O’Brien (Da Capo Press, 1996), 181.

[2] Ibid., 179.

[3] Ibid., 197.

[4] McCarter credited a bundle of blankets he placed behind his head as the reason he was protected from further injury and death. When he reached safety and unfurled them, “the receptacles of thirty-two other bullets were dropped out,” which he noted had passed through “some ten or twelve folds of thickness.” McCarter, unsurprisingly, described it as “a wonderful blanket,” Ibid., 183; 200.

[5] Ibid., 197.

[6] Ibid., 207.

[7] Ibid., 212.

[8] Ibid., 222.

[9] Ibid., 212.

[10] Ibid., 215; 217.

[11] Ibid., 217.

[12] Ibid., 210.

About the Author

Catherine Bateson is a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh, researching the sentiments and expressions of Irish American Civil War songs and music. She is also the co-founder of the War Through Other Stuff Society and social media secretary for the Scottish Association for the Study of America. You can follow her on Twitter @catbateson.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.