Table of Contents

A surgeon steps into the washroom to wash their hands for around five minutes before entering the surgical theater. A nurse assists the surgeon in donning the surgical gown and gloves so as to not break the sterile field. The surgeon recalls their years of education and training before making the first incision. Today, a surgeon usually goes through at least a decade of coursework and education before they are able to run the show in the surgical rooms. Doctors and surgeons go through a lot of training to make sure they know where to cut and where not to, proper dosage of medicines, and proper surgical procedures to make sure that their patient has the best chance possible of surviving.

Medical education did not always used to be so intensive. In the 18th and early 19th century, people could become physicians through apprenticeship with no prior experience. By the start of the 19th century, the practice of apprenticeships was starting to fade away in favor of attending lectures and performing research at a medical school. People wishing to become doctors would have to apply to a school and complete the curriculum requirements. This, along with the rise of germ theory and antiseptic practices in the latter half of the century, increased the quality of medical care and the skill of the physician. The mid-19th century also saw the dramatic increase in the number of new doctors in the country. By 1810, less than 400 people received a medical degree, “between 1850 and 1859, that number reached 17,213.”[1] Before we get ahead of ourselves too much, let us take a step back and look at medical schools before the Civil War.

While apprenticeships were available in the U.S. in the early 1800s, many hopeful physicians would apply to one of the medical schools. Throughout the 1800s, and even today, the best places to seek a medical degree were Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, and Harvard Medical School near Boston. While these schools were some of the best places in the country to learn medicine, many American doctors would advance their careers and knowledge further by studying either in England, France, or Germany which had some of the best schools in the world.

Entry requirements were much less rigorous in the 19th century compared to modern medical schools. No degree was required for admission and medical school looked more like a trade school. At Harvard Medical School, in the 1850s, the faculty was made up of practicing physicians at Massachusetts General Hospital who were in charge of setting the requirements to graduate. Students would have to complete two 16-week lecture courses in their first year, the following year they attended those exact same lectures. The faculty believed, as was the general belief at the time, that repetition was the key to learning medicine. Once this course was complete, students were required to write a medical treatise and pass an oral exam.[2]

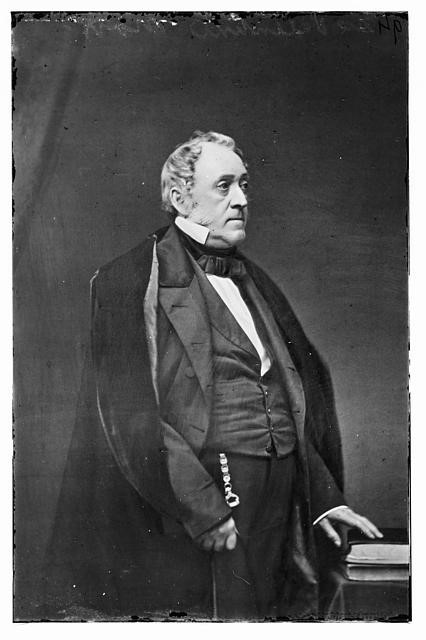

Specializations were just starting to become a standard in the medical field by the mid-19th century and it was around this time as well that medical students were able to select which lectures they attended during their time in school. Dr. Valentine Mott, regarded as one of the best surgeons of his time, wished to begin a medical school at the New York University to compete with Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons. The proposed program at New York University would send students to nearby Bellevue Hospital for them to gain not only clinical, but practical experience in medicine.[3]

Bellevue would go on to create its own medical school, opening its doors officially on April 11, 1861. The model adopted by Bellevue faculty would go on to influence future medical schools. Students at Bellevue would have immediate access to patients in the wards, witness live births and obstetrics procedures as part of their curriculum, and spend more time in the anatomy and dissection lab with cadavers acquired through the passage of the “Bone Bill.”

The “Bone Bill” allowed New York city hospitals greater access to cadavers by acquiring them from almshouses. With the rise of anesthesia fifteen years prior to the Civil War, people’s fears of doctors, hospitals, and surgery were dampened which led to a greater number of patients asking to be seen by doctors. Medical students at Bellevue were able to witness more surgical procedures and eventually would become better equipped to treat trauma-related injuries brought on by the Civil War.

The day after the Bellevue medical school opened, South Carolina militiamen attacked Fort Sumter and the Civil War began. During the war, admissions to medical colleges did not cease as doctors were always needed. Bellevue Medical College saw 36 of its students join the Union and fifteen joined the Confederacy. Those students who joined the Union were offered a certificate of completion even if they did not fully complete the four terms of lectures, completion of a published paper, and passage of an oral exam.[4]

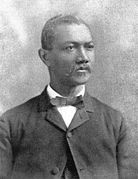

There were some groups of people who found it difficult to pursue a medical degree in the United States in the 19th century. African Americans and women were rarely, if ever, admitted into a medical school in America. Alexander Augusta, born in 1825 to free African American parents in Norfolk, Virginia, would go on to become the highest ranking African American officer in the Union Army, the first head of a hospital, Freedmen’s Hospital, and the first African American professor of medicine at Howard University. During the Civil War, Dr. Augusta was the surgeon of the 7th U.S. Colored Infantry. He was moved to the Freedmen’s Hospital at Camp Barker after his white assistants complained about being subordinate to an African American officer. Despite his incredible career, Dr. Augusta was not able to receive a medical degree in America and had to seek a medical degree in Toronto.[5]

Dr. Mary Walker became the second woman in America to become a doctor after Elizabeth Blackwell. However, she was the first, and only, woman to receive the Medal of Honor. Dr. Walker received her medical degree in 1855 but business was hard to come by as no one wanted to accept a female doctor. By the time of the Civil War, Dr. Walker offered her services to the Union Army, however she was rejected but became a volunteer nurse in Washington DC. In 1863, Dr. Walker was able to get the War Department to accept her request and she was sent to Ohio. She was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Andrew Johnson sometime after the war citing that she “has rendered valuable service to the Government, and her efforts have been earnest and untiring in a variety of ways.”[6] Several decades later, her Medal of Honor was taken away from her, but that did not stop her from wearing it. The award was not restored to her until 1977.[7] It would not be until about ten years after the Civil War that nursing schools became more popular and women started to gain more recognition in a medical role.

With the end of the Civil War, medical schools were able to use the case studies and data collected from across the country to better be able to teach medicine. The method of teaching medicine would change with the establishment of Johns Hopkins University Medical School. This was the first medical school to institute the 4-year program offering a wide variety of courses for their students.

Medical education has come a long way since the 19th century. Medicine is always changing and advancing around us, and as medicine advances, so should the way it is taught. The 19th century saw major changes in our understanding of medicine and that is reflected in the changes to the pedagogical styles of medical school. Today, doctors go through years of education and training. Who knows what the next iteration of medical education will look like in 100 years? 200 years?

Click here for a list of medical schools in the U.S. before and during the Civil War.

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021.

Sources

[1] Oshinsky, David M. Bellevue: Three Centuries of Medicine and Mayhem at America’s Most Storied Hospital. New York, NY: Anchor Books, 2017. Pg 68

[2] Hill, Jim Dan. The Civil War Sketchbook of Charles Ellery Stedman. San Rafael, CA: Presidio Press, 1976. Pgs. 10-12

[3] Oshinsky, David M. Bellevue: Three Centuries of Medicine and Mayhem at America’s Most Storied Hospital. New York, NY: Anchor Books, 2017. Pg 72

[4] Oshinsky, David M. Bellevue: Three Centuries of Medicine and Mayhem at America’s Most Storied Hospital. New York, NY: Anchor Books, 2017. Pg. 86

[5] Fenison, Jimmy. “Alexander T. Augusta (1825-1890).” Blackpast, June 8, 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/augusta-alexander-t-1825-1890/.

[6] “Mary Edwards Walker: U.S. Civil War: U.S. Army: Medal of Honor Recipient.” Congressional Medal of Honor Society, n.d. https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/mary-e-walker.

[7] Alexander, Kerri Lee. “Mary Edwards Walker.” Biography: Mary Edwards Walker, n.d. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mary-edwards-walker.