Table of Contents

For most people, the earliest image of a wounded soldier they ever see is from the Civil War. Did doctors just start using medical illustration as a teaching tool in 1861? No, military medical illustration is actually over 600 years old. Beginning in the early 1400s and continuing for several centuries after, the “Wound Man” was a staple drawing in European surgical textbooks. This illustration depicts a naked male who has been wounded by all forms of then-available weaponry: arrow, sword, sabre, club, cudgel, dagger, knife, axe, and spear. By the early 1500s, the woes of the “Wound Man” included injuries from cannon balls and gunshots from pistols and muskets. Explanations of the wounds and techniques for treatment were printed along with the picture.

Despite the tradition of the “Wound Man,” military medical illustration may be said to have come of age during the early 1860s with the outbreak of the Civil War. The founding of the Army Medical Museum (AMM) in Washington, DC in 1862 was central in this process. Because of its mandate to record and examine disease, death, wounds, and injuries due to the hostilities, a new type of organization of medical experts was assembled. Based in Washington, this network first spanned the length and breadth of the Union Army, and after the war ended, it covered the country. Military doctors regularly relayed information and specimens (tissue and bone samples) from battlefield hospitals to the AMM. Just as important, they also often conveyed sketches, drawings and photographs that depicted the damage wrought on soldiers by, for example, .58 calibre minié balls from rifles, along with other ordinance.

Critical to this project was the work of professional and amateur artists using the media of watercolor, oil, and pencil sketching. These artists were members of the AMM and served as hospital stewards in the field under the aegis of the Office of the Surgeon General. Included among them were Hermann Faber, Edward Stauch, William Schutze, and Peter Baumgras . The German ancestry of these men points to the European tradition of medical illustrating dating back to the “Wound Man.” Their works varied—with Faber being the most professional and the talented Stauch dying on duty outside Petersburg—but collectively these artists captured the immediacy of the wound and the range of the following surgeries. Much of the trauma they illustrated had rarely been recorded before as practitioners of civilian medicine just did not encounter the types of injury that were commonplace in battle.

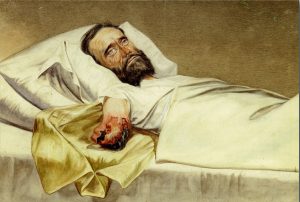

Faber’s artwork depicted feet with gangrene, a secondary amputation at the hip, ulceration of the colon, and a left humerus shattered by a minié ball. For his part, Baumgras painted, for example, a gunshot fracture of cranium by conoidal ball, a shrapnel wound of head, and a man lying on a pillow after surviving an amputation of his leg at the hip—a characterization that was more suggestive of a contemplative portrait than a medical illustration. Not all the soldiers who were subjects of these illustrations were Union Army men, occasionally a “Rebel Soldier” might also be sketched. A sharp eye, a deft hand, and drawing talent are obvious skills essential for the job of medical illustrator, but to be a military medical illustrator under the conditions that often existed in Civil War hospitals also required a strong stomach.

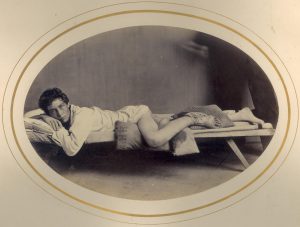

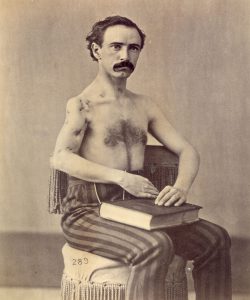

The increasing use of the relatively new technology of black and white photography, however, also differentiated this era of medical illustration from earlier times. Doctors themselves, such as Dr. Reed Bontecou of DC’s Harewood Hospital, were prolific in generating photographs of wounded soldiers initially for their own use, but soon to also be contributed to the AMM. Although an amateur photographer, Bontecou was expert in handling the cumbersome equipment of his time. This era was of course pre-digital, but was also before the advent of roll film; negatives were produced on large, fragile glass plates that were subsequently developed by hand. Artificial lighting such as it was (candle and oil lamp) was insufficient for the long exposure times needed to take photographs; all images had to be shot in daylight. Nevertheless, he and others produced an incredible photographic record of war wounds, injuries, and surgical outcomes.

An iconic image of the War produced by Bontecou entitled “Field Day” was a stack of discarded amputated legs and feet, before their disposal in a burial pit, or by cremation. This grotesque still life captured not only the results of the well-meaning efforts of army surgeons—comparatively primitive now after aseptic technique, x-rays, blood transfusion, and antibiotics have become common—but also the barbarity of war itself.

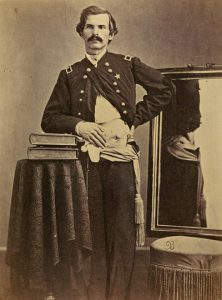

The overall photograph record produced not only benefited the world of medicine and surgery, but also the soldiers themselves. The pictorial accounts of wounds suffered in war became useful to many soldiers in their appeal for government pension payments over the next 60 years. Such photographs were submitted as medical evidence to prove soldiers’ disabilities. Augmenting all this was the work of professional photographers such as William Bell who created a new genre of medical illustration: posed portraits of surviving wounded veterans.

Often these shots included mirrors to show both the entry and exit points of a missile that traveled through the soldier’s body; or an amputee might be seated beside the bone that was once his femur.

Perhaps such scenes may appear odd or unseemly to modern eyes, but they too could serve as a proof of incapacity for official purposes. Additionally, these portraits also recorded the sacrifices made by soldiers; they were dismembered in way that was analogous to the national dismemberment that was the Civil War.

The lasting result of the Army Medical Museum’s effort to document disease, death, wounds, and injuries due to the hostilities was the six-volume, 6,000 page copiously illustrated Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, which took over twenty-three years to complete. These volumes are testimony to the important role of military medical illustration during the Civil War and set the standard for similar volumes up until the present day. An encyclopedic medical treatise based on case histories, the History is a systematic, statistical compilation of the types of injuries and diseases a military surgeon could expect to treat, along with discussions of and examples of treatments. Army surgeons John H. Brinton, George Otis, and J.J. Woodward directed the project and amassed thousands of specimens and accounts from surgeons and doctors, including Confederates, while records of the Pension Office were heavily utilized to follow up cases. Army Medical Museum specimens were photographed, and engravings, lithographs and photomechanical prints were made to illustrate the text. The giant undertaking was a triumph of medical research and ensured that the images captured in a short five year period endure today.

Additional Resources

- Connor, J.T.H. and Michael G. Rhode, “Shooting Soldiers: Civil War Medical Images, Memory, and Identity in America” Invisible Culture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture 5 (Winter 2003). http://www.rochester.edu/in_visible_culture/Issue_5/ConnorRhode/ConnorRhode.html

- Hasegawa, Guy R., Mending Broken Soldiers: The Union and Confederate Programs to Supply Artificial Limbs (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2012).

- Hill, Boyd H., “A Medieval German Wound Man: Wellcome MS 49,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 20 (1965): 334-57.

- Military Medicine and the Wound Man, USMA Library Bulletin no. 15 (West Point, NY: United States Military Academy, 1976).

- Reznick, Jeffrey S., Jeff Gambel and Alan J. Hawk, “Historical Perspectives on the Care of Service Members with Limb Amputations,” in Paul F. Pasquina and Rory A. Cooper, eds., Care of the Combat Amputee (Washington, DC: Borden Institute, Walter Reed Army Medical Center: 2009), pp. 19-40.

- Rhode, Michael G., “The Rise and Fall of the Army Medical Museum and Library,” Washington History 18 (2006): 78-97.

- Rhode, Michael G. and J.T.H. Connor, “‘A repository for bottled monsters and medical curiosities’: The Evolution of the Army Medical Museum,” in Amy K. Levin, ed., Defining Memory: Local Museums and the Construction of History in America’s Changing Communities (Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007), pp. 177-96.

Images Courtesy of the National Museum of Health and Medicine

About the Authors

J.T.H. Connor is John Clinch Professor of Medical Humanities and History of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Canada; he also holds an appointment in the Department of History. Previously, he was Assistant Director (Research and Collections) at the National Museum of Health and Medicine (formerly the Army Medical Museum). He has published widely on science, technology, and medicine in North America, as well as aspects of medical museums.

Michael Rhode was chief archivist of the National Museum of Health and Medicine’s Otis Historical Archives. Rhode had been with the museum since 1986 and in charge of the archives from 1989-2011. In between the two periods he worked at the National Archives and Records Administration. He’s currently the archivist for the US Navy’s Bureau of Medicine & Surgery’s Office of Medical History. Rhode has authored numerous papers and articles, in addition to making many presentations on medical history. Exhibits he has curated include “American Angels of Mercy: Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee’s Pictorial Record of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904,” and “Battlefield Surgery 101: From the Civil War to Vietnam.” He co-authored the catalogs for both exhibits as well.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.