Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

“That’s in the past. That’s more from the Victorian era!” Isabel Mao’s* daughter exclaimed. I was interviewing Isabel about her experiences with menstruation for my book, The Modern Period: Menstruation in Twentieth-Century America. Isabel, an immigrant from Taiwan, figured her American-born daughter must be fibbing when she claimed her swim team coach let her practice during her period. Her daughter, who had just walked into the room, rolled her eyes in protest. She explained that she was always encouraged to play in gym class and participate in sports unless she was feeling really crampy, and she had only felt the need to sit out once during high school. Isabel laughingly conceded that her worries were perhaps outdated. “Oh, that’s called Victorian. I see! Old-fashioned!”[1]

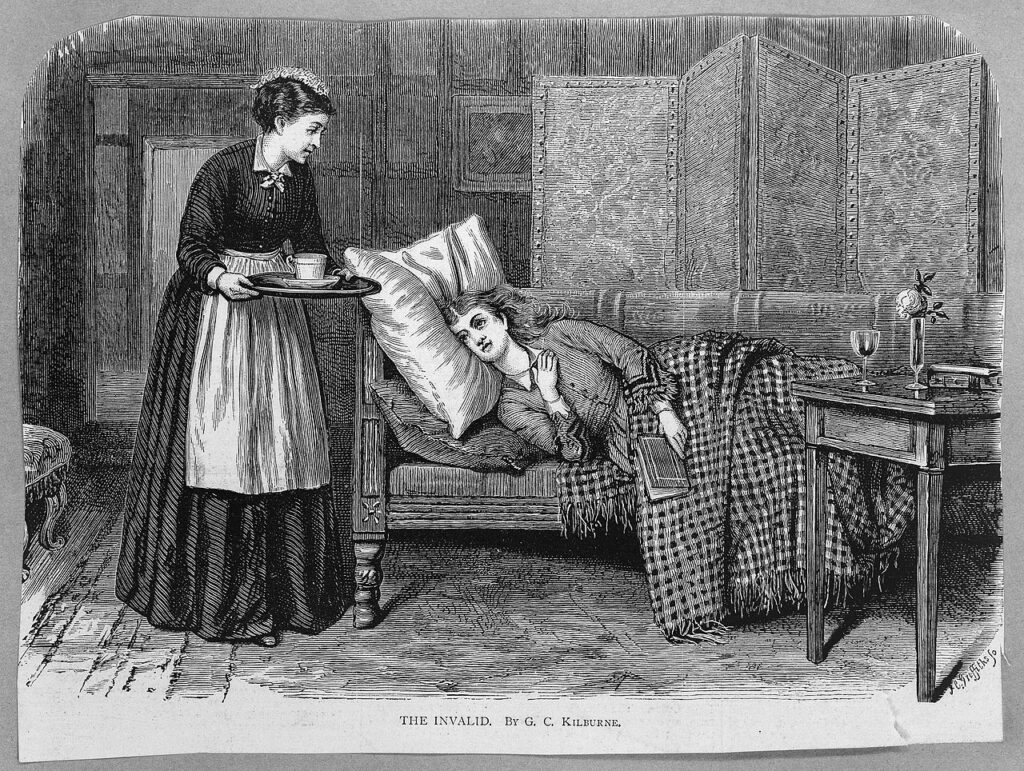

Isabel and her daughter, like many of us, associate the Victorian era with an image of a delicate woman swooning on a couch, incapacitated by her monthly visitor. Where did this image originate? And how closely did it hew to the reality of women’s lives in Victorian America?

Nineteenth century medical writers certainly seemed convinced that women were complete wrecks when they had their periods. In 1869, Dr. James MacGrigor Allan told the Anthropological Society of London that during menstruation, women were invalids, “unfit for any great mental or physical labour.”[2] In his 1891 Ladies’ Guide to Health and Disease, health reformer John Harvey Kellogg opined that it was important for girls’ development to rest completely during menstruation. A teenage girl “should be relieved of taxing duties of every description, and should be allowed to yield herself to the feeling of malaise, which usually comes over her at this period, lounging on the sofa or using her time as she pleases.”[3]

If you enjoy this article, click here to check out others on the National Museum of Civil War Medicine blog

Most women, though, did not have the luxury to lay around for a couple of days just because they were menstruating. Nineteenth-century diaries give little indication of women pampering themselves during their periods. They appear to have continued their usual household and family duties, Allan’s disparagement and Kellogg’s recommendation notwithstanding.

We can assume, however, that women did not find menstruating to be the most comfortable thing in the world. They used cloth pads tied or buttoned to belts to soak up the menstrual blood. As Mary Hanson,* who got her first period before the introduction of Kotex in 1921, explained to me, “We had diapers… they weren’t very comfortable… you’d have to shape it, fold it over, just as you put on a baby.” The cloth often chafed the inside of a woman’s thighs, especially if it was wet, making painful abrasions. Diapers were inconvenient, as well. They got in the way of urination (nineteenth-century women, who used outhouses, chamber pots, or a discreet outdoor spot, did not normally wear panties or other clothes that would need to be pulled down). And, Mary sighed, “you had to soak them and wash them and cleanse them and blah, blah, blah, and hang them up so no one would see them.”[4]

While Victorian-era women more or less carried on as usual during their periods, they did heed some of the most enduring traditions concerning menstrual health. Since at least the time of Hippocrates, doctors and laypeople alike had subscribed to a humoral understanding of the body. They believed that the four humors—blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm—needed to be properly balanced and circulating in the body to maintain health. Menstrual periods were thought to rid women’s bodies of superfluous blood. If the blood did not flow and instead stagnated in the body, it could cause all kinds of illness. Menstrual suppression that we now understand to be a symptom of systemic illnesses such as tuberculosis and cancer was, instead, assumed to cause those deadly diseases. Therefore, while women continued most of their daily work, they avoided activities they believed could halt the flow. The most salient precaution was avoiding getting chilled, whether by bathing, doing the wash in cold water, or working outside in cold, damp weather.

Isabel Mao and her daughter were right: Victorians would not have let their daughters swim during their periods. But neither did a Victorian woman swoon on a divan in the parlor, as a general rule. She strapped on a diaper under her skirts, perhaps gritted her teeth, and went about her business.

*Interviewee names are pseudonyms.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Lara Freidenfelds is the author of The Modern Period: Menstruation in Twentieth-Century America. She is currently working on a new book titled Counting Chickens Before They Hatch?: Miscarriage and the Quest for the Perfect Pregnancy. She blogs on the history of health, reproduction, and parenting for Nursing Clio. Follow her on twitter: @larafreidenfeld.

Footnotes

[1] Lara Freidenfelds, The Modern Period: Menstruation in Twentieth-Century America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), p. 103.

[2] Cited in Elaine Showalter and English Showalter, “Victorian Women and Menstruation,” Victorian Studies, v. 14 n.1, 1970, 83-89, p. 85.

[3] Cited in Freidenfelds, The Modern Period, p. 78.

[4] Ibid., p. 30-31.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.