Table of Contents

Of the many women who provided medical service during the Civil War, Mary Ann “Mother” Bickerdyke was one of the most beloved by the soldiers. She also earned the respect of Union generals, including Sherman and Grant.

Mary Ann Ball was born on July 19, 1817, in Knox County, Ohio. Her father and mother were farmers and her mother died when Mary Ann was only a year old. Mary Ann was sent along with her sister to live with her grandparents, who also lived in Ohio. When her grandparents died, her uncle cared for her. Not much else is known about her early life. Some sources say she attended Oberlin College or that she was part of the Underground Railroad, but there is no evidence to support these claims.[1]

In 1847, Mary Ann married Robert Bickerdyke and moved to Cincinnati. They had two sons, and due to Robert’s poor health, moved first to Iowa and then Illinois. In 1859, Robert died, leaving Mary Ann to fend for herself and the children. It was during this time that she began her medical career—working as a botanic physician, using alternative medicines, herbs, and plants.[2]

In 1861, the minister of Mary Ann’s church, Reverend Edward Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, sent out a plea for help for the Union soldiers stationed in Cairo, Illinois. The town collected $500 worth of medical supplies and after finding someone to care for her sons, Mary Ann traveled to Cairo to deliver them. She immediately took charge of sanitary conditions and nursing at the camp, and when a hospital was built, she was appointed matron with the blessing of the commanding general, Ulysses S. Grant.

Dr. Benjamin Woodward, who was in charge of the general hospital at Cairo, described Mary Ann’s experience:

At first the men ridiculed her, but her cheerful temper took no offense, for she knew she was right; but woe to the man who insulted her. Her first requisition was for bathing-tubs; these were made from half-hogsheads and barrels. She organized the nurses, saw that all the sick were cleaned, and, as far as possible, given clean underclothes. A special diet-kitchen was established, and a great change for the better was soon seen in the patients. As a rule, she hated officers, looking on them as natural enemies of the enlisted men.[3]

It was during this time that Mary Ann was given the nickname that would be with her for the rest of the war: “Mother Bickerdyke.” Lemuel Adams, an officer with the 22nd Illinois who was recovering in the hospital from a gunshot wound, wrote of Mary Ann:

I have seen Mother Bickerdyke sit all night by the cot of a sick and dying soldier. She never seemed to tire, and could do more work than any two nurses I ever saw. She made sure that everyone had proper attention and that no special favors were shown. Every sick or wounded soldier was the same to her, from General Grant to the newest recruit.[4]

Mary Ann was soon appointed a field agent by the U.S. Sanitary Commission, which gave her a monthly wage. Having obtained General Grant’s trust, Mary Ann was also given a pass that allowed her to follow the army and be in the camps to assist the soldiers. She followed Grant’s army to Corinth and Memphis—acting as a nurse in the subsequent battles.[5] At Vicksburg, she was appointed by Grant as chief of nursing.

Mary Ann was not only known for her adherence to cleanliness, but she was also a terrific forager. She would make many journeys into the countryside to acquire cows and chickens for meat, dairy, and eggs so that “her boys” would have a proper diet. She cared little for her own safety and well-being and although cleanly in her appearance, she wore only a simple calico dress. It was remarked that she was often so involved in her work that she was indifferent to any dangers, including “flying sparks from open fires” that would cause her dress to “take fire.” When asked if she was afraid of being burned, she replied “Oh no! My boys put me out.”[6]

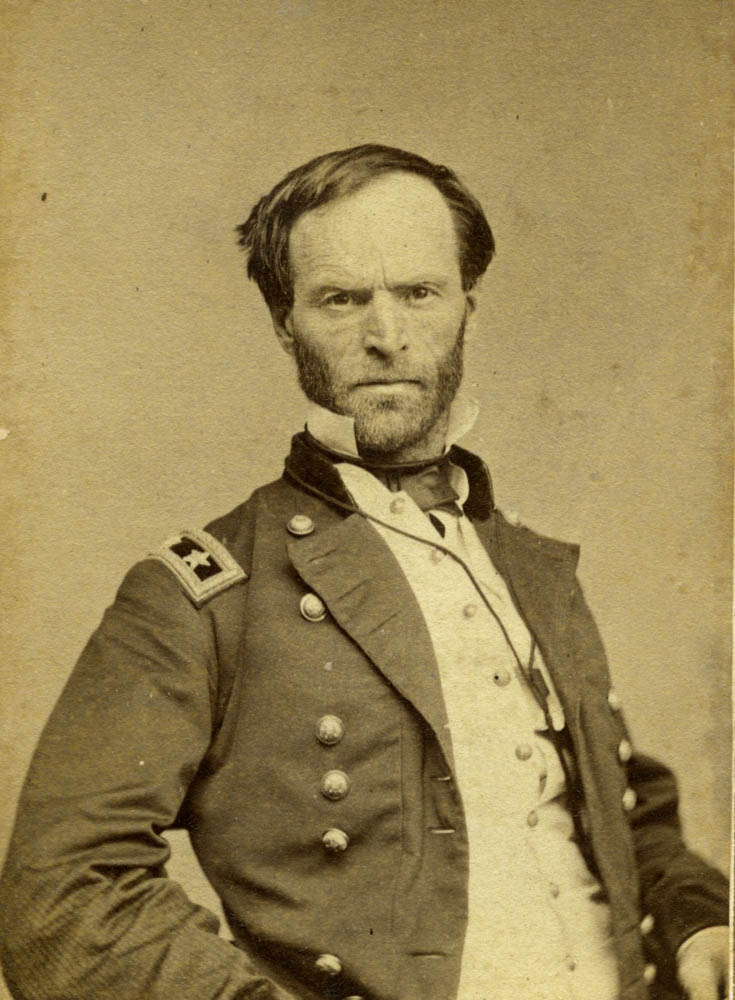

As chief of nursing, Mary Ann relentlessly pursued her task of caring for the soldiers, sometimes deliberately ignoring military procedure in the process. When members of the general staff complained about her behavior, it is said that General William T. Sherman threw up his hands and exclaimed “I can’t do a thing in the world. She ranks me!”[7] Sherman also called her “one of his best generals” and other officers referred to her as the “Brigadier Commanding Hospitals.”[8]

Sherman allowed Mary Ann to accompany him and his army on their famous march through Georgia, and she was witness to several battles, including the Battle of Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge. It was during this time that she also worked to build hospitals for Confederate soldiers as well. [9]

By the time the war ended in 1865, Mary Ann had built (with the help of the U.S. Sanitary Commission) 300 hospitals and aided the wounded on 19 battlefields. At the request of General Sherman, she was allowed to ride with the Army in the Grand Review in Washington, D.C. She continued her work to help soldiers by establishing veterans’ homes as well as helping them with obtaining pensions. She received a special pension of $25 a month from Congress when she retired to Kansas to live with one of her sons. Mary Ann Bickerdyke died in 1901 from a stroke and was buried in Galesburg, Illinois, where a statue was erected in her honor.[10]

About the Author

Tracey McIntire earned her BA in English at Rivier College in Nashua, NH. She is Director of Communications at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, and an interpretive volunteer at Antietam National Battlefield. She is also an active Civil War living historian, where she portrays a woman soldier in various guises.

Sources

[1] Lewis, Jone Johnson. “Mary Ann Bickerdyke: Calico Colonel of the Civil War.” ThoughtCo, August 26, 2020, thoughtco.com/mary-ann-bickerdyke-biography-3528676

[2] Fliege, Stu (2003). Tales and Trails of Illinois. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-07085-2.

[3] Campfire Sketches and Battlefield Echoes, 1861-1865, ed. W.C. King, 1887

[4] Litvin, Martin. The Young Mary 1817-1861: Early Years of Mother Bickerdyke, America’s Florence Nightingale and Patron Saint of Kansas, Log City Books, 1977

[5] Lewis, Jone Johnson. “Mary Ann Bickerdyke: Calico Colonel of the Civil War.” ThoughtCo, August 26, 2020, thoughtco.com/mary-ann-bickerdyke-biography-3528676

[6] Holland, Mary Gardner. Our Army Nurses: Stories from Women in the Civil War. Edinborough Press, 1998.

[7] Fliege, Stu (2003). Tales and Trails of Illinois. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-07085-2.

[8] Chase, Julia A. Houghton (1896), Mary A. Bickerdyke, “Mother.” Lawrence Kansas: Journal Publishing House.

[9] Tsui, Bonnie (2006). She Went to the Field: Women Soldiers of the Civil War. Guilford, Connecticut: TwoDot.

[10] Fliege, Stu (2003). Tales and Trails of Illinois. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-07085-2.