Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

In Part One of this series, I examined the low casualty rates of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps compared to the Army. While there are many reasons why sailors and marines were less likely to die of disease and combat than their comrades ashore, naval combat could be remarkably lethal.

By percentage of enlisted, 6.5% of the U.S. Army was killed in combat throughout the Civil War. By comparison, the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps lost only 2.7% of its enlisted to combat deaths. However, soldiers were more than twice as likely to be wounded as killed. Sailors and marines, on the other hand, were more likely to die in combat than be wounded.[1]

Why did the Union Navy suffer more dead than wounded in combat when the opposite was true ashore?

Naval warfare in the Civil War was, by its very nature, indiscriminate. There was no truly safe zone aboard a ship. A reliance on artillery as the main tool of warfare, rather than the more precise rifle, was a major factor. Another is that there was no choosing individuals to target. Surgeons and hospital stewards were largely spared if they appeared on the battlefield and the opposing side could identify them as medical professionals. Not only out of humanity, but also because they were not a threat. Indeed, those same medical professionals might end up saving the life of an enemy if they wound up under their knife.

But in naval combat you fired at ships: impersonal and imprecise. Surgeons could be struck by shells as easily as their patients or legitimate combatants. Such was the fate of a doctor on the CSS Alabama. Her first officer, First Lieutenant John McIntosh Kell later remembered: “Assistant Surgeon Llewellyn was at his post, but the table and patient on it had been swept away from him by an 11-inch shell, which made an aperture that was fast filling with water. This was the last time I saw Dr. Llewellyn in life.”[2]

By the Civil War, naval combat was focused on filling the enemy ship with enough holes to send her to the bottom, and that meant much of her crew went with her, including the wounded.

It wasn’t always this way. While naval combat has always been indiscriminate and impersonal, in the age of fighting sail, most of the time combat ended with a ship escaping or being captured, rather than sunk. And sinking ships could take hours to go down, giving ample time for evacuation. For example, at the massive Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, involving sixty ships of the line, only two were destroyed from damage sustained in combat, and a few others intentionally scuttled after the fact.[3]

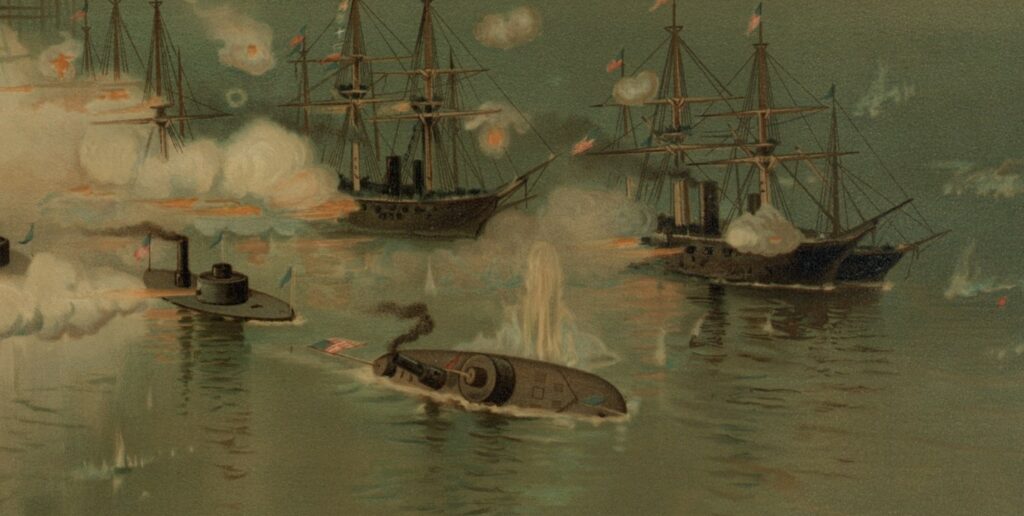

The Industrial Revolution changed all that. Ironclads began to dominate naval combat after the Battle of Hampton Roads in 1862, kicking off an arms race not only between the Union and Confederacy, but also between the United States and the rest of the world. Virtually impervious to artillery fire, ironclads like the CSS Virginia could effectively neutralize wooden fleets in a single day. They quickly made up a significant portion of naval fleets.

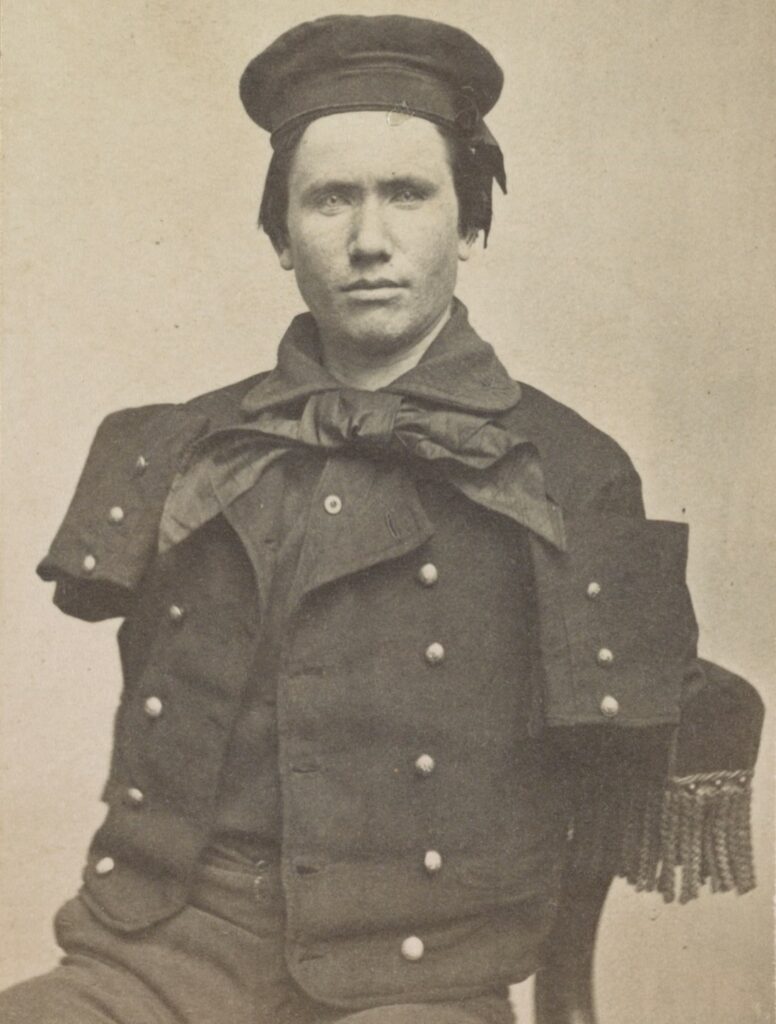

Sailors and marines unfortunate enough to serve on wooden vessels against ironclads faced horrifying odds. Surgeon’s Steward Sayres O. Nichols, who I quoted in part one in marveling how the wooden gunboat USS Miami’s shells bounced off the ironclad CSS Albemarle “without even denting her,” testified to how the Albemarle was able to tear through his crewmates:

They killed our commander, C.W. Flusser, and wounded Ensign Hargis, Enginer Harrington and ten men, Capt Flusser was awfully mangled had 19 musket balls, and pieces of shell in different parts of his body. one arm was clown off. Dr. Mann and I looked like butchers, our coats and vests off, our shirt sleaves rolled up and we covered with blood. O it was an awful sight. God grant that I may never witness the like again. As fast as the men were wounded, they were passed down to us and we laid them one at a time on the table, cut their clothes from them, and extracted the balls and pieces of shell from them. The blood was over the soles of my boots all over the berth deck, and the shrieks and groans of the wounded were heartrending.[4]

When ironclads did sink, they sank fast. Without watertight compartments, and weighed down by heavy iron, they could go straight to the bottom with little warning. At the Battle of Mobile Bay, the USS Tecumseh struck a mine and sank in ten seconds, taking nearly all her crew, including the surgeon.[5] One of the very few survivors, pilot and Acting Master John Collins, later recalled “There was nothing after me. When I reached the topmost round of the ladder the vessel seemed to drop from under me.”[6] A more experimental craft, the famous Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley suffered a similar fate. She sank three times in trials and finally in combat, drowning her entire crew in two of those.[7]

Further adding to the danger was the rise of steam engines. Almost all warships on both sides utilized steam, and a constant threat was the boiler. A lucky shot from an enemy vessel could pierce the boiler and release scalding hot steam into the vessel, burning the unfortunate victims inside and out as it was inhaled.

Compounding the dangers of sea life was isolation. Distance and weather removed the support network that army doctors could rely on. Acting Assistant Surgeon Ezra Pray of the U.S. Bark Fernandina wrote in his journal about his frustration at not being able to get a sailor suffering a bullet wound to shore:

“We are off Hatteras; and I hoped the wind would continue good so that I could get my patient into the Hospital ship before he dies; but we have the wind dead ahead, and the sea is mountain high…I got no sleep last night and stand no chance to get any to night. But 12 is the clock, and an unhappy day is ended.”[8]

Further evidence of this isolation can be seen in the kits carried afloat by naval surgeons from the collection of the National Museum of Health and Medicine. Naval kits included unusual items like the trephine and tooth key. For comparison: the U.S. Army only performed about 230 trephinations over the course of the entire war, a miniscule number compared to the tens of thousands of capital amputations seen on terrestrial battlefields.[9]

Armies could rely on support networks to bring up whatever obscure instrument a surgeon might need in a delicate or unusual operation. Naval surgeons, however, might only be able to use what they already had on the ships, especially if they were in blue water service and away from the blockade.

The dangers of steam, isolation, and rapid sinking were not present for soldiers in the field, and they contributed to the imbalance in combat casualties and the deaths of naval medical personnel.

For example, roughly 170-180,000 soldiers were involved in the Battle of Gettysburg, but only one surgeon was killed.[10] By contrast, despite involving far smaller numbers over a much shorter period, the USS Keystone State lost two medical men and eighteen others to a single lucky shot fired from a blockade runner that pierced her steam drum.[11]

Although by no means entirely out of danger, surgeons and stewards ashore could sometimes find safety from the battle behind the lines. More importantly, they could choose to avoid combat.

Hospital Steward Theo Brown of the 3rd U.S. Infantry later recalled his reaction to a rare case of the medical team working in an active combat area:

“We, the hospital party, could have probably done much more good had we stayed farther away from the battlefield…Our presence on the battlefield was, in my opinion, calculated simply to swell the list of dead and wounded, and of pensioners. I also resolved that any future war I should participate in should not find me in the role of a combatant-non-combatant.”[12]

Naval surgeons had no such option to remove themselves and their patients from the danger.

Sailors and marines were less likely to be killed in combat than soldiers, and less likely to succumb to disease. When they did see combat, it could be remarkably lethal. As a period of transition, the Civil War saw a chaotic blend of old and new that was expressed in politics, power, social mores, transportation, communication, arms, and medicine. This made for an era defined by the good and the bad. Examining naval casualties highlights this fact. The Civil War was a terribly destructive conflict that still impacts us to this day, so examining and understanding its contradictions and consequences is a vital task.

If you missed it, click here to read part 1.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Kyle Dalton is the Membership and Development Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is also a summa cum laude graduate of the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, where his paper Active and Efficient: Veterans and the Success of the United States Ambulance Corps was awarded the Zeender Prize for best history thesis. In his spare time Kyle writes and maintains a website on the lives of common sailors in the eighteenth-century: BritishTars.com.

Endnotes

[1] Leland, Anne and Mari-Jana Oboroceanu, American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics, Congressional Research Service, RL32492, updated September 24, 2019, page 2, <https://crsreports.congress.gov>.

[2] Kell, John McIntosh, Recollections of a Naval Life, Washington: Neal Company, 1900, pages 248-249.

[3] “Battle of Trafalgar,” Wikipedia, accessed February 11, 2021, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Trafalgar>.

[4] Nichols, Sayres O., “Fighting in North Carolina Waters,” Roy F. Nicols editor, The North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. XL, Number 1, Winter 1963, page 79, via Internet Archive, accessed February 22, 2021, <https://archive.org/details/northcarolinahis1963nort>.

[5] Leland, Anne and Oboroceanu, Mari-Jana, American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics, Congressional Research Service, RL32492, updated September 24, 2019, page 2, <https://crsreports.congress.gov>.

[6] Quoted in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, Volume 34, 1892, page 267, via Google Books, accessed February 11, 2021, < https://www.google.com/books/edition/Frank_Leslie_s_Popular_Monthly/CYrQAAAAMAAJ>.

[7] “H.L. Hunley,” Wikipedia, accessed February 12, 2021, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H._L._Hunley_(submarine)>.

[8] “Transcript of Journal of Acting Assistant Surgeon Ezra Pray US Bark Fernandina: September 1861-April 1862,” Navy Historical Foundation, accessed February 12, 2021, <https://www.navyhistory.org/2012/02/civil-war-journal-surgeon-ezra-pray/>.

[9] Correspondence with Terry Reimer to the author, January 26, 2021.

[10] Kirkwood, Ronald D., “The War Came Knocking on Spanglers’ Barn Door,” History Net, accessed February 12, 2021, <https://www.historynet.com/the-war-came-knocking-on-spanglers-barn-door.htm>.

[11] “Killed in Action Memorial: Civil War,” Navy Medicine, accessed February 12, 2021, <https://www.med.navy.mil/Pages/KIAInfoView.aspx?ERA=Civil%20War>; “Keystone State,” Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed February 12, 2021, <https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/k/keystone-state.html>.

[12] Brown, Theo. V., “Gaines’ Mill: A Hospital Steward’s Sketchy Picture of a Day with Bullets and Bandages,” transcribed by Jake Wynn, National Museum of Civil War Medicine, accessed February 12, 2021, <https://civilwarmed.321staging.com/explore/bibs/memoirs/steward-memoirs/>.