Table of Contents

“Everybody wants to have a hand in a great discovery. All I will do is to give a hint or two as to names—or the name—to be applied to the state produced and the agent. The state should, I think, be called ‘Anaesthesia.’ This signifies insensibility—more particularly … to objects of touch.”

–Oliver Wendall Holmes in an 1846 letter to William T. G. Morton, the first practitioner to publicly demonstrate the use of ether in an operation

The term “Renaissance Man” is not used much anymore, but it certainly can apply to Oliver Wendall Holmes, who in his lifetime was a teacher, a poet, a doctor, and an inventor as well as the person who coined the term “anesthesia.”

Holmes was born on August 29, 1809, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He began writing poetry at an early age and at 16 he was admitted to Harvard College. After graduation, he attended Harvard Law School but soon learned that being a lawyer was not what he wanted. He began to write more poetry with much success but realized that he could not earn a living on writing alone.

In 1830, he entered Boston Medical College. Holmes was shocked by what he considered to be the “painful and repulsive aspects” of medical treatment—which at the time included bleeding and cupping.[1] In 1833, he traveled to Paris to continue his education, studying under internal pathologist Pierre Charles Alexandre Louis, who demonstrated the ineffectiveness of bloodletting and a more humane approach to patient care.[2] He returned to Boston and received his Doctor of Medicine degree from Harvard in 1836.

While Holmes continued to write, he spent more time in the medical world—joining the Massachusetts Medical Society and the Boston Society for Medical Improvement. A strong proponent of the use of the stethoscope and the microscope, Holmes continued to criticize traditional medical practices and began concentrating on lecturing and teaching—eventually joining the faculty at Dartmouth Medical School in 1838.[3]

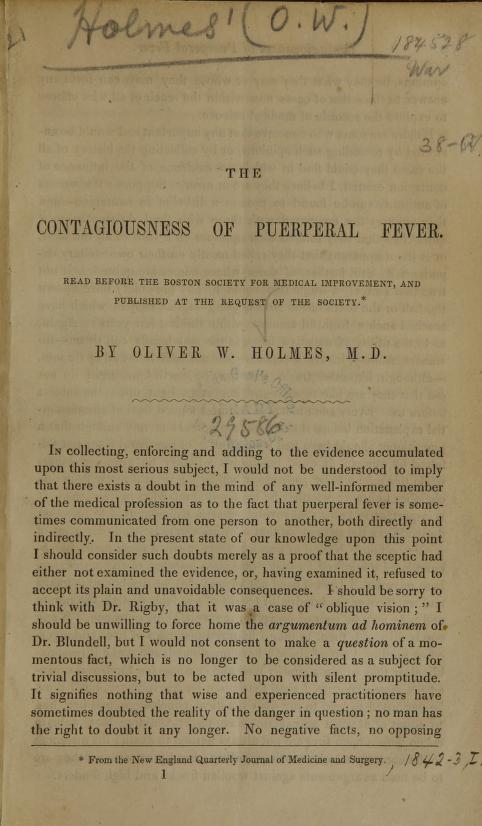

In 1840, Holmes resigned from Dartmouth and devoted his time and writing talent to lectures that exposed what he saw as medical fallacies—including the practice of homeopathy. From 1842 to 1843, he became interested in puerperal fever, or “childbed fever,” which was one of the leading causes of death in women bearing children. His resulting essay “The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever” was published in the New England Quarterly Journal of Medicine and Surgery. At a time when the germ theory of disease was literally unknown, Holmes stated that the fever was transmitted from patient to patient by contact with their physician. Holmes advocated that doctors who treated anyone with the fever should purify their instruments and burn all clothing and bedsheets that came in contact with the patient.[4]

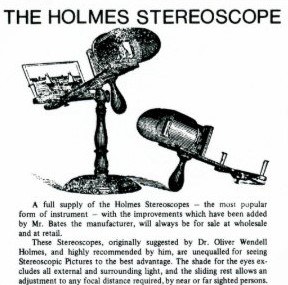

In 1846, after hearing of the use of ether in surgery, Holmes coined the term “anesthesia.” He then began a tenure at Harvard Medical School, where he would remain until 1882. He also traveled extensively, giving medical lectures and continued writing both poetry and prose. His first novel, Elsie Venner, was published in 1859. Holmes also found the time to invent the stereoscope, an early method of viewing three-dimensional photographs. The device would become extremely popular during the Civil War, with photographers such as Mathew Brady tailoring their photos to the new technology.

With the coming of the Civil War in 1861, Holmes’ concern centered on his son, Oliver Wendall Holmes, Jr., who had volunteered in the Union Army. Holmes published a famous account in the Atlantic Monthly of his search for his wounded son after the Battle of Antietam. Oliver Holmes, Jr. would later go on to become a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.

In his later years, Holmes continued writing both poetry and prose, including a biography of his friend, Ralph Waldo Emerson. He traveled back to Paris in 1884, where he met the famous biologist, Louis Pasteur. In 1886, he was awarded an honorary law degree from Yale University. Holmes died peacefully in his sleep on October 7, 1894, leaving an incredible legacy in both the literary and medical worlds.

Sources

[1] Small, Miriam Rossiter. Oliver Wendell Holmes. Twayne’s United States authors series, 29. 1962.

[2] Dowling, William C. Oliver Wendell Holmes in Paris: Medicine, Theology, and The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table. 2006.

[3] Sullivan, Wilson. New England Men of Letters. 1972

[4] Hoyt, Edwin Palmer. The Improper Bostonian: Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes.1979.

About the Author

Tracey McIntire earned her BA in English at Rivier College in Nashua, NH. She is Lead Educator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, site manager of the Pry House Field Hospital Museum, and an interpretive volunteer at Antietam National Battlefield. She is also an active Civil War living historian, where she portrays a woman soldier in various guises.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.