Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

The American Civil War created a huge demand for hospitals that neither the North nor the South could meet early in the war. Newly enlisted men would be ill with various contagious diseases before even seeing combat. Once fighting occurred, injured men joined the previous casualties of camp illnesses and discovered that healthcare resources were limited: few doctors, limited ambulances, untrained detailed nurses from the enlisted ranks, no medical supplies, and not even a place for the wounded or infected to lay their heads. The military medical department often needed temporary hospital space after a battle, so they occupied hotels, barns, farmhouses, tobacco warehouses, and even the rotunda of the US Capitol. As the war went on, it became clear that more permanent hospital spaces were essential.

The Surgeons General of both the United States and the Confederate States began a search for the most efficient and effective hospital design. Healthcare officials on opposing sides decided to utilize the pavilion-style hospital design. These hospitals were already in use throughout Europe, especially France and England, and had been favorably discussed in the literature at the time.

The design featured long narrow wards or units that incorporated multiple windows located in opposing pairs for cross-ventilation. Additional design features included other types of supplemental ventilation, specified heat sources, bed placement, square foot requirements for windows, cubic foot requirements per patient, nonporous building materials, building length to width ratios, door placements, location of support rooms, the number of stories, and the location of the sewers. Construction design considerations even specified the orientation of the wards based on the compass for maximum sunlight and the distance between wards based on the height of the buildings for maximum ventilation.

Hospital staff, especially in Europe, noticed that the death rates in some hospitals were much lower than in others. The numbers were obvious, but the reasons were not, so they began to study what made some hospitals have better outcomes than others. While many physicians investigated this outcome and what impact hospital design played in it, one person in particular played an important role. Florence Nightingale studied the design and survivability of hospitals used during the Crimean War and later widened her study to include other European hospitals.

Nightingale conducted extensive research and even applied statistics to her findings. She, as well as other physicians, came to the conclusion that the pavilion design often had the best outcomes. While ventilation was the primary focus, Nightingale also observed many other factors. She publicized her findings so that the evidence could be applied to practice and soon new hospital construction included these findings. In an age many consider to be medically archaic, medical professionals were making connections between good ventilation, cleanliness, and health (see Surgeon General William Hammond’s A Treatise on Hygiene for an example of this). To us, greater cleanliness and ventilation leading to greater health seems an obvious connection, but then it was one in a series of significant steps to better care.

The first pavilion-style hospital to be constructed was Chimborazo in Richmond, VA. Built in October 1861, it included 150 pavilions containing 4,000 beds. It remained the largest hospital in the South throughout the war.

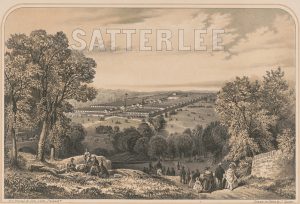

In Philadelphia, Satterlee or West Philadelphia US General Hospital opened in June of 1862 with 36 pavilions containing more than 3,500 beds. An additional 150 tents were located around the buildings for overflow in the event of an emergency or nearby engagement. Several other pavilion-style hospitals of comparable size quickly followed in the North.

Due to the rapid increase in the number of sick and wounded as the war transpired, many of the pavilion hospitals were “fast-tracked”. Satterlee was said to be a pet project of General Hammond and was quickly built. The design variations evolved over the war as flaws were discovered and rectified in future construction projects. The earlier pavilions of Satterlee were too tightly placed and impeded ventilation. Because of the pressing demand, some pavilion hospitals were not constructed from the ground up, but structures already in use were converted to the pavilion-style. Campbell Hospital in Washington was one such conversion, having already been constructed and used as cavalry barracks. It opened in September 1862 with 11 pavilions and 900 beds; it was haunted by design flaws.

The design would continue to be used throughout the Civil War especially by the North. The pavilion-style design became the premier hospital design, both military and civilian, in the decades following the conflict. Today, the design is considered obsolete and outdated. Most hospitals now favor private patient rooms, yet many of the design specifics such as ventilation and light are still considered important.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

William T. Campbell, Ed.D, RN has been a student of the Civil War for over 50 years. The historical spark was ignited as a youth growing up in southern Delaware when his aunt would frequently take him to visit Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania battlefields. With his later profession as a Registered Nurse this interest evolved into the study of medicine and nursing during the 1860’s. His research includes Civil War nurses & nursing, Hospital Stewards, Fort Delaware POW health issues, and the pavilion-style hospital.

Dr. Campbell holds a Doctor of Education from the University of Delaware, a Master of Science in Family Nursing from Salisbury University, and undergraduate degrees in Nursing, Psychology, and Biology from the University of Delaware. He completed pre-pharmacy studies at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy & Science. An Associate Professor in the Nursing Department at Salisbury University in Salisbury Maryland he teaches in the pediatrics, pharmacology, and nursing history courses. He has served as a volunteer docent at the Pry House Field Hospital Museum on the grounds of Antietam Battlefield and as a frequent speaker for the National Museum of Civil War Medicine.