Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

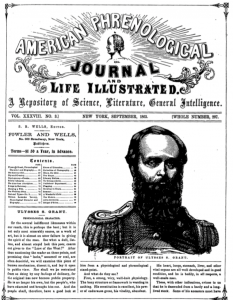

Jenkin Lloyd Jones yearned for mail. A Union soldier camped in Alabama in the muddy March of 1864, he missed his family and often felt a sense of gloom. When at last Jones received a package from home, he rushed to his tent and tore it open. Inside he found small but precious gifts: a pair of socks knit by his mother; a diary from his brother; and issues of the Phrenological Journal, his most cherished periodical, bound up with calico.

“The whole so impressed me with the scenes of home and its endearments that I could hardly refrain from tears,” he wrote.

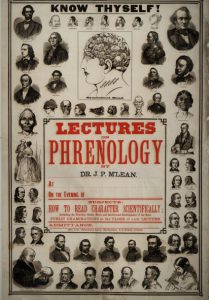

Jones, like many Americans in the mid-nineteenth century, took an interest in phrenology. Devotees of this controversial science believed that the shape of one’s skull reflected the form of the brain and therefore revealed inner character. Practical phrenologists examined the contours of their clients’ crania to chart propensities like “alimentiveness” (appetite and digestion), “philoprogenitiveness” (love of family), and “constructiveness” (mechanical ingenuity).

Though phrenologists suggested that people naturally had different strengths and weaknesses of character, self-improvement remained a possibility. If a person recognized deficiency in a particular organ, they could exercise it like a muscle, and in time it would grow.

Before the Civil War, phrenology played an ambivalent role in debates about race and the conflict over slavery. On one hand, phrenologists tended to believe that white men had the most highly-developed intellects of all groups. On the other hand, they also thought that people of other races had the potential to advance. George Combe, a renowned phrenologist, compared the skulls of free African Americans living in the north to their enslaved counterparts in the south. He claimed that the skulls of free people were better-developed, suggesting that freedom itself had “brought the moral and intellectual faculties into more active employment.” Over time phrenology became associated with the antislavery cause. Reformers of many kinds, including temperance advocates, suffragists, prison reformers, and educators, found phrenology congruent with their visions of social progress.

Beyond reform circles, phrenology had broad appeal, and mentions of the practice appear in accounts of daily life during the war. Sarah Emma Edmonds, a woman who famously disguised herself as a man to enlist in the Grand Army of the Republic, recounted her war experiences in a memoir. As she told the story, she volunteered to become a spy for the Union, but first she had to undergo a phrenological examination. She passed when the examiner found that she had the qualities needed for espionage: her “organs of secretiveness, combativeness, etc., were largely developed.”

Other soldiers debated the impact of war on their phrenological characters. In Virginia prisoners of war ruefully considered their sleeping conditions. Emaciated and covered by thin garments, they slept on the floor and used boots for pillows. Some anticipated phrenological damage from the boot-pillow, while others “allowed that it would improve our fighting qualities by an enlargement of that organ.”

As an observational practice, phrenology often served to affirm what its adherents already believed. For instance, the New York-based American Phrenological Journal and Life Illustrated —the magazine that Jenkin Lloyd Jones so savored — offered phrenological profiles of Civil War military leaders that northern audiences could cheer. The Journal assured readers of the firm character of general Ulysses S. Grant: “There is sufficient Executiveness to give force, perseverance, and efficiency, while there is large Cautiousness, to make him careful, considerate, judicious, and mindful of danger.”

The Journal also explained how a trained eye could see beyond Robert E. Lee’s noble bearing to discern his moral deficiencies: “[When we] note the lowness of the upper head, we instantly comprehend how, with all those splendid qualities, he could commit so monstrous an error as to throw them all upon the wrong side in the greatest question that arose before him and his generation for decision.”

Works Consulted

- Bittel, Carla. “Woman, Know Thyself: Producing and Using Phrenological Knowledge in 19th-Century America.” Centaurus 55, no. 2 (May 2013): 104–30.

- Davies, John D. Phrenology, Fad and Science: A 19th Century American Crusade. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1955.

- Eby, Henry Harrison. Observations of an Illinois Boy in Battle, Camp and Prisons, 1861-1865. Mendota, IL: Eby, 1019.

- Edmonds, S. Emma E. Nurse and Spy in the Union Army. Hartford, CT: W.S. Williams & Co., 1865.

- Fabian, Ann. The Skull Collectors : Race, Science, and America’s Unburied Dead. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

- Hamilton, Cynthia S. “‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother?’ Phrenology and Anti-Slavery.” Slavery and Abolition 29, no. 2 (June 2008): 173–87.

- Jones, Jenkin Lloyd. “An Artilleryman’s Diary.” Wisconsin History Commission: Original Papers 8 (February 1914).

- McCandless, Peter. “Mesmerism and Phrenology in Antebellum Charleston: ‘Enough of the Marvellous.’” Journal of Southern History 58, no. 2 (May 1992): 199-230.

- “Robert E. Lee.” American Phrenological Journal and Life Illustrated 40, no. 3 (September 1864): 88.

- “Ulysses S. Grant.” American Phrenological Journal and Life Illustrated 38, no. 3 (September 1863): 65-67.

- Wrobel, Arthur. “‘Corroborating His Phrenology’: The American Phrenological Journal, The Great American Crisis, and U. S. Grant.” Journal of American and Comparative Cultures 24, no. 3/4 (Fall 2001): 161–69.

About the Author

Kate Duffy is a Ph.D. candidate in American Studies at Brown University. She is writing a dissertation on phrenology and public culture in the antebellum United States.

og:image:https://civilwarmed.321staging.com//wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Phrenology-2.jpg

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.