Table of Contents

It is a Saturday night, I am writing a paper in the common room of the fire station in Gettysburg. Tones drop in the station and our crew for the night was dispatched to the college campus because someone had a bit too much to drink at a party. Our four-person crew operating ambulance 54-2 with Adams Regional EMS spring into action. We hop in the ambulance and prepare our equipment for the task ahead. We receive more detailed information from the dispatch center and hit the lights and sirens as we pull out of the station and head to campus. We make it to the scene and begin taking care of the patient who is quite intoxicated. At the time I was still an observer, so I was the lucky one to hold the emesis (vomit) bag. One thing I learned pretty quickly as a college EMT was to carry emesis bags in a place that is easily accessible, it ended up being my left-leg pocket.

The Gettysburg College EMS Club and Adams Regional EMS College Division was formed to serve the medical needs of Gettysburg College and be the campus’ dedicated ambulance. Made up of students, we responded to all medical calls on campus since the founding of the club my first year of college in 2017. In the summer of 2022, I took an EMT training course and passed the National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians exam becoming an EMT.

Gettysburg College’s Civil War Era Studies departments dedicates itself to the continuing education of the Civil War and its legacy. One of the most influential aspects of Civil War Medicine is the creation of the United States Ambulance Corps. In 1862, Dr. Jonathan Letterman created the Ambulance Corps, a section of the Medical Department that was specifically trained and dedicated to the first aid and transportation of the wounded. Previously, ambulances were controlled by the Quartermaster and often used for the transportation of supplies such as food and tents, sometimes even ammunition. The medical infrastructure in the early years of the Civil War was extremely poor until Dr. Letterman came along. The Letterman System, a set of procedures for handling mass casualty incidents, was introduced during the battles of South Mountain and Antietam. During these two battles, the Ambulance Corps and the Letterman System succeeded in their task and evacuated the wounded from the battlefield to a field hospital in a timely manner. This system would spread throughout the Union armies. After the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865, Commercial Hospital in Cincinnati created the first civilian ambulance service.

Jonathan Letterman and Surgeon General William Hammond completely reorganized the hospital and ambulance systems. Together they updated procedures and made improvements to the current hospital system which decreased infection rates and increased the survivability of various wounds. The revamped hospital system and the brand-new Ambulance Corps laid the groundwork for the success of Commercial Hospital’s civilian ambulance as well as future civilian ambulance companies. The ambulance operated by Commercial Hospital carried a driver, a surgeon, and some basic medical supplies for use on their patients.

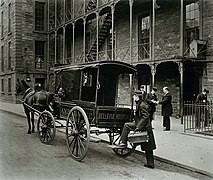

Commercial Hospital, right along the Ohio River, was a staging ground for surgeons, nurses, and supplies to get to the front in support of Grant’s efforts to capture Fort Donelson in 1862. The wounded in turn would then be taken by steamer back to Commercial Hospital for further treatment if necessary. The success of the Ambulance Corps in the Civil War prompted Commercial Hospital to establish the first civilian emergency medical system followed by New York City’s Bellevue Hospital in 1869.[1]

Dr. Edward Dalton, a former doctor with the Ambulance Corps, was the father of the Bellevue Hospital ambulance service. His ambulances were equipped in a manner similar to that of modern ambulances, their supplies included “a quart flask of brandy, two tourniquets, a half-dozen bandages, a half-dozen small sponges, some splint material, pieces of old blankets for padding, strips of various lengths with buckles, and a two-ounce vial of persulphate of iron.”[2] While modern ambulances carry a much wider variety of supplies, the basic tools and equipment that are usually the most readily available to EMTs today are very similar to that of Dr. Dalton’s ambulances.

By the 1890s, five more hospitals around New York City adopted their own dedicated ambulances. Over the next several decades, civilian ambulance systems spread throughout the country and the world to make medical care of the local populace more efficient. Over a century after the first civilian hospital ambulance was introduced, Congress passed the Emergency Medical Services Systems Act in 1973,[3] giving states and the federal government the authority and funds to create their own emergency medical services. Since then, ambulances and the Emergency Medical Service (EMS) have become an integral part of our daily lives. Today, every city, town, or county has multiple ambulances or ambulance services operated by thousands of Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs), and Paramedics.

The level of training for EMTs and Paramedics has drastically changed since the days of Commercial Hospital and Bellevue Hospital’s civilian ambulance services. There are training programs across the nation and in every state for those wanting to become an EMT. The program I was trained in combined clinical knowledge in assessing a patient, as well as hands-on skills to treat a patient’s injury.

Much like my training, the training of members of the Civil War Ambulance Corps included the proper loading and unloading of patients into the ambulances, Dr. Jonathan Letterman describes, “instructing his men in the most easy and expeditious method of putting men in and taking them out of the ambulances, taking men from the ground, and placing and carrying them on stretcher, observing that the front man steps off with the left foot, and the rear man with the right, etc.”[4] However, their training did not include first aid or proper lifesaving measures that we know today. Those roles were mostly left to the Hospital Stewards, Assistant Surgeons, and Surgeons. Much of the training for modern EMTs involves repetition and the constant practicing of skills, I could not tell you how many times I practiced securing a patient to a backboard, splinting various joints, or performing trauma and medical assessments.

In New York City, ambulances were dispatched through a telegraph system that relayed information to the hospital for the doctor and driver to arrive in the most efficient manner. Today, emergencies are usually run through a 9-1-1 call center and distributed to the proper station or service. The modern medical services owe much to the minds of Dr. Jonathan Letterman and Dr. Edward Dalton. These men pioneered the ambulance service at the time and in doing the research, post-war ambulances and modern EMS systems are not as far apart as one would think. The ambulance services created by Commercial Hospital, now UC Medical Center, and Bellevue Hospital remain in service to this day.

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021. He is currently pursuing a Masters in American History from Gettysburg College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute.

Sources

[1] Graham, Jed. “The History of the Ambulance.” Medium. History of Yesterday, May 9, 2020. https://historyofyesterday.com/the-history-of-the-ambulance-ecc2d63fb1a6.

[2] Erich, John. “EMS Hall of Fame: The Pioneers of Prehospital Care—Dalton.” Hmpgloballearningnetwork.com, July 2021. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/emsworld/original-contribution/ems-hall-fame-pioneers-prehospital-care-dalton.

[3] Congress.gov. “S.2410 – 93rd Congress (1973-1974): Emergency Medical Services Systems Act.” November 16, 1973. http://www.congress.gov/.

[4] Letterman, Jonathan. Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac. Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, 2008. Pg 24-25