Table of Contents

It is no secret that the Civil War had a devastating impact on soldiers’ bodies. Many are the stories that vividly recount piles of amputated limbs next to the surgeon’s table. For some, amputation served as a kind of double loss – one of limb, the other of manhood. How could one till fields or perform industrial work with a missing arm or leg? Who would willingly marry a man who was less than whole when so many able-bodied men were readily available?

Others, however, saw the loss of a limb as something decidedly different. An amputation could serve as a means to illustrate personal sacrifices for the war, as was the case with Major General Dan Sickles. In one of the more colorful stories of the Civil War era, Sickles donated his amputated limb to the Army Medical Museum (AMM) after losing it at the Battle of Gettysburg. Along with his leg he made sure to send a note that read, “Compliments of Major General D.E.S.” Sickles went on to visit his leg at the AMM and share war stories on the anniversary of its amputation.

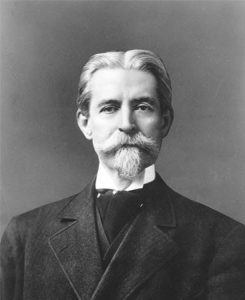

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, CM Bell Collection

As the war lengthened the destruction to men’s bodies increased exponentially. All told, between 50,000 – 60,000 amputations took place throughout the four-year war. To put it simply, men were losing limbs…lots of them. But then an odd quirk of fate occurred. Within the empty sleeves of those orphaned limbs were the seeds of an entirely new industry, one that mirrored the increasingly mechanized system of the mid nineteenth century. By its very nature this industry embodied the spirit of “replaceable parts.” I am referring to, of course, prosthetics.

Perhaps prescient of the long, destructive conflict to come, the first amputation occurred in the spring of 1861, at the Battle of Philippi. In an effort to control the western regions of Virginia, untrained and unprepared troops in the Union and Confederate armies skirmished in the vicinity of the Allegheny Mountains. Eighteen-year-old James Edward Hanger was one such young soldier. A native of Churchville, Virginia, he was enrolled in Washington College when the war broke out. Like many young students, Hanger withdrew from his studies to join a Confederate unit from his hometown. On the morning of June 3, just two days after his enlistment, he found himself reeling from Union artillery fire. Amidst the chaos a cannonball struck his left knee, shattering his leg. According to Hanger’s accounts, he remained within the stable for a number of hours before Union forces found him. After assessing the wound, Dr. James D. Robinson of the 16th Ohio Infantry, amputated the limb just below the hip joint.

After his release from a military prison Hanger returned home. Though surrounded by family, he preferred his solitude rather than suffer the social embarrassment associated with disability.

“I cannot look back upon those days in the hospital without a shudder,” Hanger said. “No one can know what such a loss means unless he has suffered a similar catastrophe. In the twinkling of an eye, life’s fondest hopes seemed dead. I was the prey of despair. What could the world hold for a maimed, crippled man!”

Hanger’s distinction as the only amputee victim of the war would not last long. Even as he recuperated in isolation from his loved ones, the war was assiduously providing him with one-limbed compatriots.

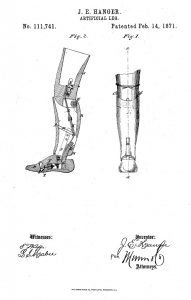

As time passed, Hanger came to terms with his missing limb. What once seemed a “catastrophe” soon became a challenge. Hanger began to fashion a homemade prosthetic made out of barrel staves and rubber tendons. His design, aptly named the “Hanger Limb,” was drastically different than the traditional “legs” of the era. Rather than create a stiff peg, Hanger’s prosthetic included hinges around the knee and ankle, thus allowing him a more natural gait. Though he could not know it at the time, this innovation revolutionized the field of prosthetics.

The following year, Hanger started a prosthetics business in Staunton, Virginia and began distributing artificial limbs to those in need. The popularity of the “Hanger Limb” grew and he soon won a state contract to produce limbs for his fellow Virginians.

His business continued to expand in the postwar years and in 1871, he received a US Patent for his designs. In 1888, he moved his business to Washington D.C. and opened additional manufacturing centers in St. Louis, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Baltimore, and Atlanta. In 1906, he incorporated his business into the J.E. Hanger Company.

Hanger’s innovations kept pace with the modernizing world of the early twentieth-century. Industrialization and war virtually ensured the growth of the prosthetics industry. Yet, rather than rest upon his previous success, Hanger felt compelled to develop a more lightweight, aluminum leg. “The Dural” leg debuted in 1912, just two years before the world became embroiled in a devastating global war. His previous experience during the Civil War prompted him to open an office in Europe so that he could more adequately provide artificial limbs to maimed WWI soldiers.

Hanger passed away in 1919, but his legacy had an indelible impact on the growth of the industry as a whole. Thanks to his tenacity and leadership, Hanger Inc. remains at the forefront of prosthetic and orthotic innovation today.

Learn More in this interview with historian Moyra Williams Schauffler about her research on prosthetic limbs

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this or donate to help preserve prosthetic limbs.

BECOME A MEMBER Arm and a Leg Campaign

Further Reading

- Brian Craig Miller. Empty Sleeves: Amputation in the Civil War South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015).

- Guy R. Hasegawa, Mending Broken Soldiers: The Union and Confederate Programs to Supply Artificial Limbs (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2012).

- Matthew Lively, “JE Hanger Lost His Leg But Not His Ingenuity,” Civil War Profiles, March 13, 2013, http://www.civilwarprofiles.com/j-e-hanger-lost-his-leg-but-not-ingenuity.

- “The J.E. Hanger Story,” Hanger, Inc.: http://www.hanger.com/history/Pages/The-J.E.-Hanger-Story.aspx.

About the Author

Dr. William R. Feeney is an historian of the nineteenth century with a specialization in the American Civil War. He currently holds a position with Muhlenberg College. His dissertation, “Manifestations of the Maimed: The Perception of Wounded Soldiers in the Civil War North,” investigates the cultural impact of disabled soldiers on citizens and the military during the war period.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.