Table of Contents

Although quackery is everywhere acknowledged to be a crying evil, some appear to think that it should not be opposed. You can do nothing, they say, to suppress or diminish it; it is useless to try… Will any physician who regards the honor and usefulness of his profession, or any intelligent citizen who values the good of society, stand still and look on in culpable apathy whilst the tide of empiricism rolls on, prostrating at the same time the honor of the profession and the best interests of humanity? … It is idle to say that nothing can be done.”

—Dr. Dan King, M.D. (1858)

In his 1858 book, Quackery Unmasked, Massachusetts physician Dan King identified the various forms of nineteenth-century “quackeries” he deemed most dangerous to public health. In the early nineteenth century, so-called “patent medicine” peddlers traveled the country selling their secret formulas, which were often disparaged as “snake oils.” Uncounted cancer doctors, bonesetters, inoculators, and abortionists operated without professional sanction. Female practitioners, Native American healers, and clergymen offered medical care in the homes of sick patients, despite their lack of formal education and training. Representatives of new medical sects, including homeopaths, Thomsonian doctors, eclectics, and hydropaths offered allegedly natural cures that ran counter to thousands of years of knowledge accumulated by the medical profession. King argued that antebellum Americans had become “great lovers of nostrums,” devouring whatever was new with “insatiable voracity.”

This was the state of affairs on the eve of the Civil War, despite widespread efforts from the American medical profession to get their house in order. In fact, accusations of medical quackery had long been pointed in the other direction, at mainstream medical doctors (those with medical degrees). For the first two-thirds of the nineteenth century, detractors had denounced so-called “regular” physicians as “learned quacks.” Critics identified “learned quackery” with aggressive and depletive “heroic” therapies that depended on an allegedly outdated and overly speculative “rational” approach. Regular practitioners were pejoratively portrayed by their critics as “mineral doctors,” “poison depletive quacks,” “mercury dosers,” “drug doctors,” and “the knights of calomel and the lancet.” Their entire system of regular medicine, meanwhile, was characterized as “a murderous system” and “the mineral, humbuggery practice.” Patent medicine promoters railed against the dangers of regular medicine and its heroic manifestations. Advertising campaigns capitalized on fear, depicting death, suffering, and evil at the hands of regular doctors.

Meanwhile, the Civil War helped launch a revolution in journalism and advertising that made it possible for drug advertisers to more effectively reach their potential customers. High-volume patent medicine makers were the first American manufacturers to seek out a national market, the first large-scale producers to go directly to consumers with a message about their product, and the first to employ a multitude of psychological techniques to entice buyers. Advertisements in newspapers and magazines were complemented by pamphlets, calendars, almanacs, storybooks, cookbooks, joke books, and various other publications that sprinkled ads throughout the text like commercials in a modern television show. In addition to exploiting fears, advertisements played on patriotic sentiments by depicting American war heroes and even presidents in their advertisements. Within a month of Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, an ad for Bellingham’s ointment appeared on the front page of the New York Herald, claiming credit for the new president’s magnificent beard.

Courtesy of the New York Historical Society

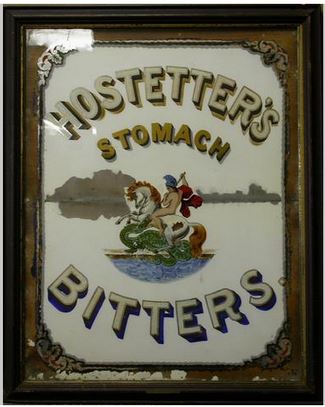

The Civil War had a major impact on themes used by advertisers to sell their remedies, including increased attention to the “prevailing difficulties” faced by soldiers like diarrhea and dysentery. Brandeth’s Pills used the testimony of “Sixty Voices from the Army of Potomac” as evidence for their effectiveness in protecting the soldier from “the arrows of disease, usually as fatal as the bullets of the foe.” An officer in the Shenandoah Valley reportedly considered Hostetter’s Bitters “The Soldier’s Safeguard.” A pamphlet for Piper’s Magical Elixir insisted the makers of this remedy for diarrhea had gathered testimony from satisfied customers in part so their product might be known to “those braves, so many of whom have fallen a prey to disease at the Seat of War.”

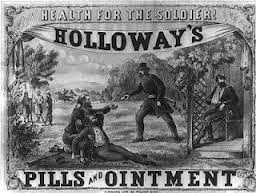

Advertisers used the Civil War to sell a wide range of remedies during and after the conflict. See’s Army Linament promised to ease aches and pains. The Union Hair Restorative offered a cure for baldness. Holloway’s Pills used the image of a blue-clad officer hurrying a box of the remedy to a fallen soldier in one of its many war-themed posters. Drug makers also targeted the thousands of soldiers who returned to civilian life after recovering from wartime illnesses. Dr. Williams Medicine Company, maker of Pink Pills for Pale People, lamented: “It is not alone those who were wounded who deserve our sympathy, it is the great majority who were not, but who contracted the seeds of disease in Southern swamps and prisons, and who have as a consequence lost their health before their time.”

In the wake of the war, reformers remained steadfast in their belief that public education could curb the excesses of the most egregious quacks while critics still unhappily noted that the demand for cure-alls and for the services of those who claimed to cure by extraordinary means was “not confined to those who are deficient in intelligence or weakened and discouraged by exhausting diseases.” Before the war, reformers had likewise admitted that they could never expect quackery’s complete extermination. “History informs us,” Dr. King noted in 1858, “that it has always existed in some form or other, and a consideration of the human propensity leads us to conclude that it always will.” In the years following the Civil War, even the most ardent medical reformers often admitted that “the ‘quack,’ the ‘shyster,’ and the ‘sheep in wolf’s clothing’” would always exist.

About the Author

Eric W. Boyle earned his PhD in the History of Science, Technology and Medicine from the University of California Santa Barbara in 2007. He was Chief Archivist at the National Museum of Health and Medicine from 2013-2016 and is currently Chief Historian for the Department of Energy and a lecturer for the University of Maryland’s School of Public Health. His first book, Quack Medicine: A History of Combating Health Fraud in Twentieth-Century America, was published in 2013.

Works Consulted

- Aschner, Bernard. “Empiricism and Rationalism in Past and Present Medicine” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 17 (1945: 269-86).

- “Dangerous Forms of Quackery.” Medical and Surgical Reporter 10 (September 26, 1863): 300.

- Dixon, Edward H. A Treatise on Diseases of the Sexual Organs: Adapted to Popular and Professional Reading, and the Exposition of Quackery, Professional and Otherwise (New York: Taylor, 1845).

- Eggleston, William, Austin Flint and R. Ogden Doremus, “The Open Door of Quackery,” The North American Review 149 (Oct., 1889): 483-504

- Frederick Fact. “Stop Thief!!! King Calomel Outlawed. Being an Hours Peep at the Mother of All Medical Mischief,” (Boston: 1834), 2.

- Jameson, Eric. The Natural History of Quackery (London: Michael Joseph, 1961).

- King, Dan. Quackery Unmasked: A Consideration of the Most Prominent Empirical Schemes of the Present Time, With An Enumeration of Some of the Causes Which Contribute to Their Support (Boston: David Clapp, 1858). https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-57310420R-bk.

- Mason, Augustus. The Quackery of the Age: A Satire of the Times (Boston: White, Lewis & Potter, 1845). https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101198816-bk

- “Military Quackery.” Medical and Surgical Reporter 6 (June 22, 1861): 260.

- Murison, Justine S. “Quacks, nostrums, and miraculous cures: narratives of medical modernity in the nineteenth-century United States,” Literature and Medicine 32 (Fall 2014): 419-440, 494.

- Nutting, J.H. “An Essay on Some of The Principles of Medical Delusion,” (Boston: David Clapp, 1853).

- Parascandola, John. “Patent Medicines in Nineteenth-Century America,” Caduceus 1 (1985): 1-39.

- Payne, F. R. “Quackery.” Medical and Surgical Reporter 14 (March 10, 1866): 198.

- Philadelphia Medical Society, First Report of the Committee of the Philadelphia Medical Society on Quack Medicines (Philadelphia: Judah Dobson, 1828).

- Warner, John Harley “Science in Medicine,” Osiris 1 (1985): 37-58.

- Young, James Harvey. The Toadstool Millionaires: A Social History of Patent Medicines in American before Federal Regulation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.