Table of Contents

During the 19th century, there were many social barriers that prevented women and African Americans from pursuing medical careers. One person who overcame both racism and sexism to become a respected doctor was Rebecca Lee Crumpler.

Crumpler was born in Christiana, Delaware on February 8, 1831, to Matilda and Absolum Davis. For unknown reasons, she was raised by her aunt in Pennsylvania. Because her aunt served in place of a town doctor, Crumpler was exposed to the medical world from an early age, stating that “having been reared by a kind aunt in Pennsylvania, whose usefulness with the sick was continually sought, I early conceived a liking for, and sought every opportunity to relieve the sufferings of others.”[1]

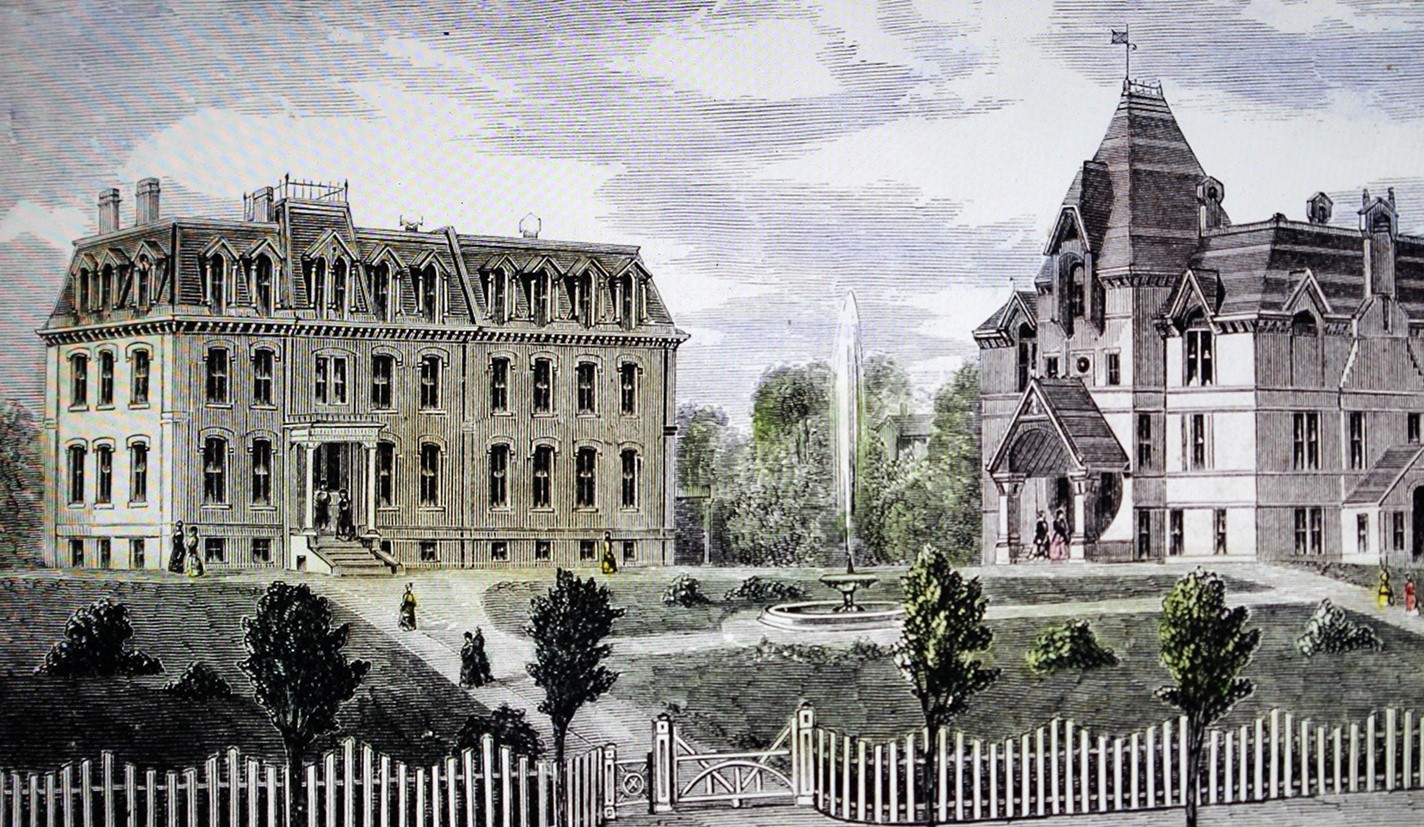

In 1852, Crumpler decided to pursue a medical career, and moved to Charlestown, Massachusetts, where she worked as a nurse. During this time, she met and married Wyatt Lee, a formally enslaved man from Virginia. In 1860, Crumpler’s talent was recognized by the physicians she was working for, and she was given recommendations to attend the New England Female Medical College, one of only two schools in the United States that would accept women students. While Crumpler was one of many women pursuing a medical career at this institution, she was the only one who was African American.

Crumpler was accepted into the college, but her studies came to a brief halt in 1861, due to the outbreak of the Civil War. She continued her nursing, and in 1863, after the death of her husband from tuberculosis, was able to return to the college. Financially strapped, she was able to finance her studies after winning a tuition award from the Wade Scholarship Fund, established by Ohio abolitionist Benjamin Wade. In March 1864, after completing three years of coursework, a thesis, and final oral examinations, Crumpler was named a Doctor of Medicine by the school. She was the only African American graduate from the New England Female Medical College, and the first African American woman in the United States to become a formally trained physician.[2]

Crumpler began her practice in Boston, primarily caring for poor African American women and children. In 1865, at the end of the Civil War, she decided to move to Richmond, Virginia, to address the urgent need for medical care among the newly freed African Americans. Crumpler felt that Richmond would be “a proper field for real missionary work, and one that would present ample opportunities to become acquainted with the diseases of women and children.”[3]

Crumpler attained a position with the Freedmen’s Bureau, which provided medical care to African Americans who had been denied care by white doctors. During this time, she was subjected to racism and sexism by both the Bureau’s administrators and other physicians. Her medical opinions were often ignored, and she had trouble getting her patients’ prescriptions filled. Some of the staff said that the M.D. behind her name stood for “Mule Driver.”[4]

On May 24, 1865, Crumpler married her second husband, Arthur Crumpler, a formerly enslaved man who had escaped from Virginia. He had served with the Union Army at Fort Monroe as a blacksmith. In 1862, he moved to Massachusetts, where it is presumed, he met his future wife. They had one daughter, although it is thought that she died in infancy.[5]

After working in Richmond for many years, Crumpler and her husband returned to Boston and took up residence in an African American community on Beacon Hill. Crumpler wrote that she “returned to her former home, Boston, where I entered into the work with renewed vigor, practicing outside, and receiving children in the house for treatment; regardless, in a measure, of remuneration.”[6] Crumpler’s medical practice specialized in treating both women and children, and emphasized good nutrition and preventative medicine.

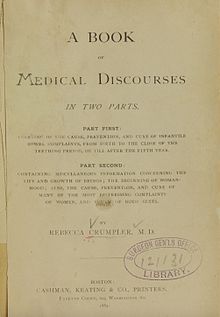

By 1880, Crumpler had retired from her practice and moved with her husband to Hyde Park, Massachusetts. She was still active in the medical world, however, and she began writing a book based on her years of practice that she hoped would advocate for preventative medicine. The book, titled A Book of Medical Discourses: In Two Parts, was published in 1883. Its primary focus was on women’s and children’s health, featuring both conventional and homeopathic treatments. The first part of the book discussed intestinal problems from infancy to age 5, and the second part discussed puberty and the accompanying health issues. In addition to medical advice, Crumpler also added her thoughts on marriage, and political and social issues. Crumpler’s book was one of the very first medical publications by an African American.[7]

Rebecca Lee Crumpler died on March 9, 1895, in Fairview, Massachusetts. Although there are online images that claim to be of her, none have been verified. A Boston Globe article described her as “a very pleasant and intellectual woman and an indefatigable church worker . . . tall and straight, with light brown skin and gray hair.”[8] Her husband Arthur died in May 1910, and they were both buried in unmarked graves. In 2020, because of an appeal by the Friends of Hyde Park Library, headstones were finally added to the gravesite. The Rebecca Lee Society, one of the first medical societies for African American women, was named after her, and her legacy continues to inspire many to overcome racism and sexism in pursuit of their dreams.

About the Author

Tracey McIntire earned her BA in English at Rivier College in Nashua, NH. She is Lead Educator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, site manager of the Pry House Field Hospital Museum, and an interpretive volunteer at Antietam National Battlefield. She is also an active Civil War living historian, where she portrays a woman soldier in various guises.

Sources

[1] Crumpler, MD, Rebecca. A Book of Medical Discourses: In Two Parts, 1883. p. 158.

[2] Women’s History blog, 2008, Rebecca Lee Crumpler

[3] Henry Louis Gates; Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. African American Lives, March 2004, pp. 199–200

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Rebecca and Arthur Crumpler”, Hyde Park, Norfolk, Massachusetts, United States Federal Census, Washington, D.C.: National Archives, 1880

[6] Crumpler, MD, Rebecca. A Book of Medical Discourses: In Two Parts, 1883. p. 158.

[7] Women’s History blog, 2008, Rebecca Lee Crumpler

[8] Herbison, Matt. “Is That Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler? Misidentification, Copyright, and Pesky Historical Details,” Drexel University, June 18, 2013.