Table of Contents

It was nearly 10:00 a.m. on July 1, 1863, and the Battle of Gettysburg was underway. The famed Iron Brigade advanced through fields west of town, onto McPherson Ridge, and into Herbst Woods. There, this collection of Midwestern blue-clad United States soldiers plunged into the fray, with the 302 officers and men of the 2nd Wisconsin in the lead.[1]

Among the ranks was Pvt. Elisha Rice Reed of Company H, a 27-year-old Ohio native and graduate of the Methodist Seminary at Evansville, Wisconsin, who had already been wounded, captured, and paroled earlier in the Civil War. After their stout defense of McPherson Ridge for nearly five solid hours, Reed and his comrades withdrew eastward to Seminary Ridge, where they made a last stand. For the men in Company H, virtually every officer above the rank of major was a casualty by day’s end, including the leaders of their company, division, and corps, as well as three successive regimental commanders.[2]

“When Lee came upon us in the afternoon of the first day in McPherson’s woods we had not fallen back very far before I was shot through both legs,” Reed later wrote. As his regiment sought protection behind a hastily constructed barricade of fence rails near the Lutheran Theological Seminary, Reed was first hit in the upper side of his right thigh. “It was a minié ball, and as I felt it cutting and tearing through the flesh, I did not need a post-mortem examination to tell me that I was winged at last,” he realized promptly, when at “about the same instant another ball came crashing through the other leg, so very near to the artery that I felt sure that it must be cut.”[3]

As the Federal line began to break amid withering Confederate fire, Reed faced a difficult decision. “I realized in a moment that if the artery were cut at that point, I had not more than one chance in a thousand of living an hour,” he recalled. “I also knew that no power on earth could save me unless I got a compress on it immediately….To stop there and tie up my leg would be to fall into their hands in about one minute,” he pondered, while to “run might insure my bleeding to death.” “No bones were broken,” he observed, and thus he decided he was well enough to flee on foot.[4]

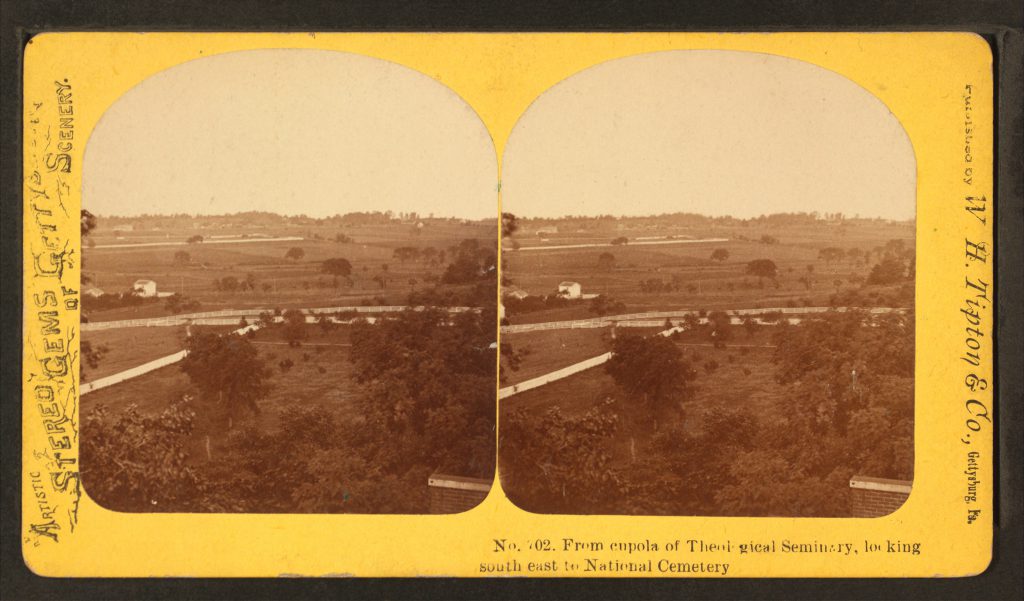

“I ‘limbered to the rear rapidly,’” he later remembered, all the while bearing the weight of his gear, as well as the constant fear of seeing “arterial blood” from his potentially mortal wound. He made his way a few hundred yards to the multi-storied brick seminary edifice, where he noticed “the grounds outside and the whole of the lower story were already crowded with the dead and dying, while those who were able had gone up the stairs.” Reed found it in himself to attempt the latter, and climbed to the chapel on the building’s third floor where he sought medical assistance from a lieutenant in the 24th Michigan, a fellow Iron Brigade regiment.[5]

Reed was one in a sea of “many others who were disabled” and had taken refuge in the seminary, where as many as 700 patients were eventually treated from July 1 to Sept. 16, 1863. In what at first seemed like a safe place of refuge, Reed and other Union soldiers soon learned that the “First Army Corps swept past, closely followed by the Confederates, on through the town and up to Cemetery Hill.” As Rebels began their occupation of the seminary, food, water, and medical supplies were removed and transported elsewhere; “the enemy had possession of the town and we were prisoners,” Reed had unfortunately concluded. “Thus ended the first day at Gettysburg.”[6]

Despite his noncombatant role on the battle’s final two days, to Elisha Reed, July 2 and 3 produced terrible memories. “The second day was full of horrors to those of us who were at the seminary as prisoners,” he wrote; “the surrounding grounds being elevated, were occupied by about 140 pieces of Confederate artillery, the music of which, altogether with the effects of shots from the Union artillery upon the building and surrounding grounds, occasioned the most extreme anguish to us all. The noise, resounding through the building, was worse than ordinary artillery.” That day, he described, a “lieutenant with a leg off, was thrown into nervous excitement and died,” while another man whose arm was “shattered” went insane, “rushed wildly about the building, down stairs and away—and he never came back.” Yet even at that, Reed grieved, “The third day was worse than the second.”[7]

It was July 3, as well, which provided Reed with a sight that would forever fill his memories of Gettysburg. “On the afternoon of the third day I happened to be up in the cupola of the Seminary and had a good view of Picket’s [sic] charge,” he wrote. “There was also a rebel Lieu’t in the cupola,” alongside about a dozen “Yanks” (likely several wounded soldiers, like Reed) who “rejoiced exceedingly when they saw the result” of the failed Confederate assault a mile-and-a-half southward. “We went below and ‘told the boys,’” Reed proudly reminisced, who “rejoiced with a loud noise” while gathered in the chapel, “the largest room in the building.”[8]

Then the Confederate lieutenant—who, Reed added, “saw nothing to make him rejoice”—entered the room, “slowly, sadly, and silently.” He “walked around for some time,—looking at no one—speaking to no one.” Eventually, Reed explained, “like the ‘pent-up thunders in the earth beneath’ he broke forth in a raging torrent of long suppressed wrath.” As if he could not himself believe it, Reed implored anyone reading his passage, “Imagine if you can an enraged southern fire-eater pouring out volcanic clouds of vigorous and vehement volumes of profanity—calling Lee a fool,” and verbalizing “all the profane adverbs and adjectives qualifying” the word “fool.” The Confederate chieftain should never have set out on his mission of “undertaking to dislodge” the Union army “from that position over there,” the irreverent Rebel declared.[9]

According to Reed, the irate southerner went so far as to say that Lee’s army “can’t do it—and he knows he can’t do it. Then,” he pondered, “why in hell does he try to do it”? By Reed’s recollection, the Confederate officer’s tantrum continued for another paragraph’s worth of text, which featured a description of Pickett’s Charge as nothing more than “sending those men into a rat-trap from which they could never get out.” Through all of the pontification and vulgarities, Reed observed, “In short—it was evident to him that somebody had blundered.”[10]

“By the fourth day the Confederate batteries were silenced, and only the ‘distant and random gun’ of the pickets could be heard,” Reed later noted, regarding the day after the battle’s effective conclusion. “The morning of the fifth day dawned, beautiful and bright, and the last Confederate had disappeared. The wounded prisoners were now all free.” Despite his initial fear, he survived his lesions, and was afterward transferred out of active service to Washington, D.C., where he found a role in the Veteran Reserve Corps.[11]

After his three-year enlistment was up, the seasoned combatant returned home, having been wounded five times during the war. He married, had five children, and at various points moved to Missouri, Kansas, and back to Wisconsin. Reed remained an active participant of Grand Army of the Republic as a member of Post No. 41 in Evansville, Wisconsin. He died on Feb. 26, 1923, at age 87.[12] While we can’t know how often Reed replayed his memories from Gettysburg, we can be sure they stayed with him long after the guns fell silent.

A membership to the National Museum of Civil War Medicine not only supports us, but gets you free admission and other benefits to our affiliate museums like the Seminary Ridge Museum in Gettysburg. So what are you waiting for? Click here to become a member today.

Footnotes

[1] Jno. Mansfield, letter to Capt. J.D. Wood, “Report of Maj. John Mansfield, Second Wisconsin Infantry,” in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1889), series 1, vol. 27, part 1, 273-275. John Mansfield was the third man who commanded the 2nd Wisconsin at Gettysburg, Col. Lucius Fairchild and Lt. Col. Nathaniel Rollins having been wounded. Of the 302 officers and men engaged, Mansfield reported 233 were killed, wounded, or missing, on July 1 (a casualty rate of 77 percent), leaving the regiment with only 69 unscathed troops. “The casualties to the regiment resulting from this day’s fight, for the numbers engaged, are believed to be unparalleled in the history of the war,” wrote Mansfield.

[2] “Elisha Rice Reed,” in Soldiers’ and Citizens’ Album of Biographical Record Containing Personal Sketches of Army Men and Citizens Prominent in Loyalty to the Union (Chicago: Grand Army Publishing Company, 1890), 283-284. Elisha Reed’s initial wound came at First Bull Run, when a “ball…had broken the point of the shoulder blade.” He was subsequently taken prisoner at Fairfax Court House, and imprisoned at Richmond, Virginia; Tuscaloosa, Alabama; and Salisbury, North Carolina. After he was paroled in May 1862, he returned home for a brief furlough, where he found “that his friends believed him a dead man.” Before their mistake was realized, his loved ones had planned a funeral, and thus upon receiving the news of his positive wellbeing, “he was received by many as one from the grave.”

[3] Elisha Rice Reed, “General Lee at Gettysburg, Pa.,” undated and unpublished manuscript, University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries, The State of Wisconsin Collection, 5; E.R. Reed, “A Private’s Story,” Milwaukee Sunday Telegraph, June 12, 1887, 3 (special thanks are due to Lori Bessler at the Wisconsin Historical Society for providing a copy of this article); for more on Reed during this time, also see Lance J. Herdegen, Those Damned Black Hats! The Iron Brigade in the Gettysburg Campaign (New York and El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie LLC, 2008, 2013), 157.

[4] Reed, Telegraph; Reed, “General Lee at Gettysburg,” 5.

[5] Reed, “General Lee at Gettysburg,” 5; Reed, Telegraph.

[6] “E.R. Reed (Co.H, 2d Wisconsin),” in J.H. Stine, History of the Army of the Potomac (Philadelphia: J.B. Rodgers Printing Co., 1892), 731-732. For a full study of the Seminary Hospital, see Michael A. Dreese, The Hospital on Seminary Ridge at the Battle of Gettysburg (Jefferson, NC, and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2002). Also see Abdel Ross Wentz, History of the Gettysburg Theological Seminary of the General Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the United States and of the United Lutheran Church in America, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 1826-1926 (Philadelphia: The United Lutheran Publication House, 1926), 191-214.

[7] Reed, Telegraph; History of the Army of the Potomac, 732.

[8] Reed, “General Lee at Gettysburg,” 5-6.

[9] Reed, “General Lee at Gettysburg,” 5-6.

[10] Reed, “General Lee at Gettysburg,” 6-7.

[11] History of the Army of the Potomac, 732; Soldiers and Sailors Album, 283-284.

[12] Soldiers and Sailors Album, 283-284.

About the Author

Codie Eash serves as Visitor Services Coordinator at the Gettysburg Seminary Ridge Museum, where he delivers battlefield tours on the campus of the historic Lutheran Seminary, including the famous cupola. He earned a bachelor’s degree in communication/journalism from Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania in 2014, and maintains the Facebook page “Codie Eash – Writer and Historian” and the blog “Ramblings from the Ridges” at www.CodieEashWrites.com.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.