Table of Contents

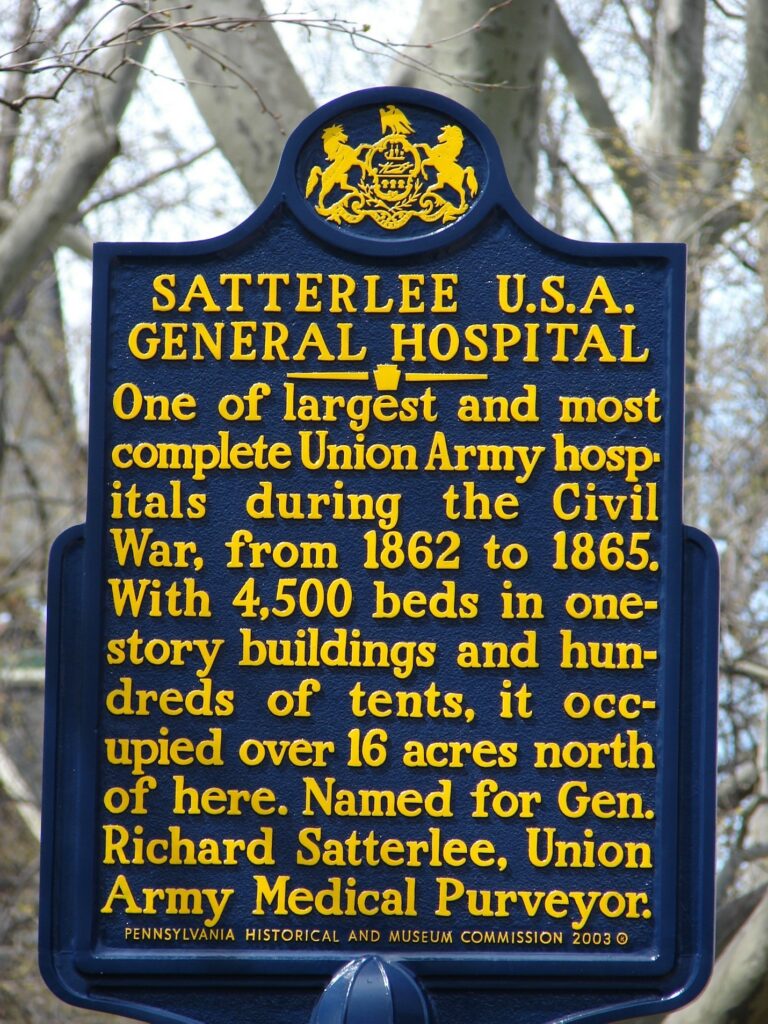

At the onset of the Civil War, the U.S. Army’s largest hospital had only 40 beds and was located in Kansas. Needless to say, in a war that saw nearly half a million wounded, larger hospitals would be essential. After the Battle of First Bull Run in 1861, military planners began to put more of a focus on creating larger hospitals. A rising star in the medical field Dr. William Hammond, was appointed to Surgeon General in 1862 and got to work reshaping hospital systems throughout the Union. One of the more well-known hospitals of his creation was Satterlee Hospital. From its opening in 1862 to the time its doors closed in 1865, over 50,000 soldiers passed through its wards.

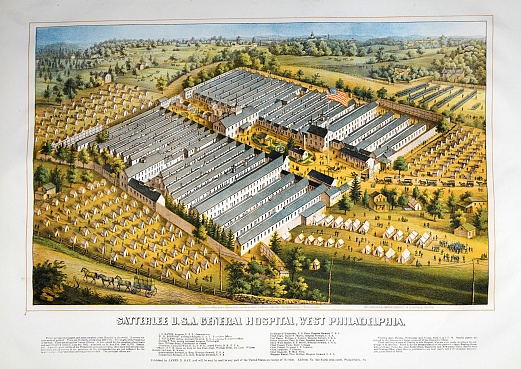

Shortly after his promotion to Surgeon General, Dr. Hammond ordered the construction of a massive hospital on the outskirts of Philadelphia. There were many other hospitals throughout Philadelphia, but none were comparable in size to Satterlee. Pavilion hospitals were one of the many innovations to come out of the Civil War. Usually revolving around a central building, different wards would be attached or adjacent to the central building where patients were usually separated based on their condition. Ideally, pavilion hospitals would be located near a water supply to bring in fresh water for cooking, cleaning, and bathing as well as a safe place to drain sewage and human waste. Satterlee was one of the few pavilion hospitals with a municipal water supply.

Hospitals in the 19th century had horrifically high mortality rates due to infection. During the Crimean War, nurse Florence Nightingale changed how hospitals were viewed with her ideas of hospital sanitation. Taking her work into consideration, Dr. Hammond and other American doctors created hospitals like Satterlee. Satterlee had 33 wards totaling 2,500 beds on 16 acres of land.[1] It would later be expanded as the number of patients received increased. Soldiers from the Battle of Second Bull Run to Gettysburg and beyond were brought to Satterlee Hospital.

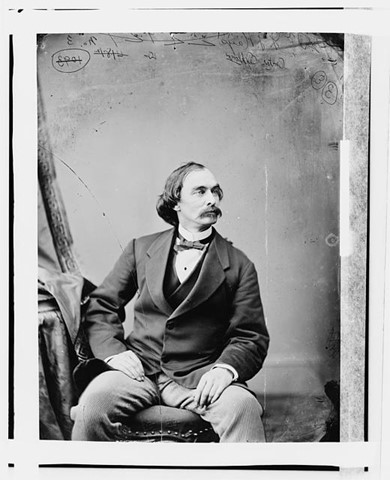

The man put in charge of Satterlee Hospital was Dr. Isaac Israel Hayes. Before taking his role as the planner of Satterlee, Dr. Hayes signed on as a ship’s surgeon during several Arctic Circle expeditions searching for lost British explorer Sir John Franklin. Dr. Hayes was regarded as both a brilliant surgeon and planner who was able to handle high pressure situations.[2] Dr. Hayes was able to successfully manage the largest Union hospital and the second largest hospital on the North American continent, the largest was Chimborazo Hospital in Virginia. To assist the medical personnel with the treatment of soldiers, Dr. Hayes asked the Daughters of Charity and the Roman Catholic Sisters of Charity to serve as nurses. These women lived in a convent on the main campus of Satterlee and “would change the bed sheets, empty the chamber pots, dress festering wounds, and most importantly, offer emotional solace to those lonely men in agony, far from home and loved ones.”[3]

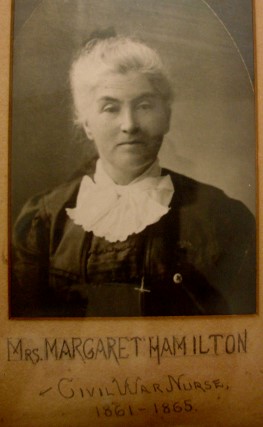

Throughout the nation, women proved their value and dedication within the medical field while serving as nurses. One nurse, Margaret Hamilton of the Sisters of Charity, came to Satterlee as it opened in 1862. In those early days, the hospital was understaffed, undersupplied, and overwhelmed. Despite this, the doctors and nurses battled disease with distinction with Margaret later writing, “the first week after the arrival of these wounded and fever-stricken boys, we scarcely had time to eat, rest, or sleep. Our corps of nurses was insufficient for the demand made on their time by the terrible sufferings of the sick and dying.”[4]

Margaret continued to write about some of the horrific wounds she encountered while at Satterlee as well as about a female soldier who entered the ward she was in charge of after the Battle of the Wilderness. She wrote, “among them was a young woman not more than twenty years of age. She ranked lieutenant. She was wounded in the shoulder, and her sex was not discovered until she came to our hospital… and the boys who were brought in with her said that no one in the company showed more bravery than she.”[5] It is estimated that between 400 and 1,000 women served in active combat roles throughout the Civil War, and many were only discovered after a wounding or sickness.

Satterlee Hospital saw soldiers pass through its doors from almost every major engagement of the Civil War. Private John Worrall of the 59th New York was wounded at the Battle of Antietam and taken to Satterlee for treatment. Private Worrall was wounded by a fragment of a shell which hit the left temporal bone above the eye, it then cut through his skull and passed through the top of his head. As he was being evacuated to a field hospital, he was struck by a bullet which injured the nerves of his arm. Private Worrall was moved to Satterlee on September 27th where he received further treatment. He recovered from his wounds sometime later and was discharged two years later in 1864 with the rest of his regiment.[6] Private Worrall survived the war and is reported as being examined by a pensioner in 1869.

Private G. Hodges of the 7th MI was wounded on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg and was transferred to Satterlee Hospital the following week. Acting Assistant Surgeon M. J. Grier recorded the wound as follows, “a shot wound of the left knee by minie ball passing over the patella, cutting through the outer laminae of the ligamentrum patella and scratching the surface of the knee.”[7] On multiple occasions, the wound reopened itself for a variety of reasons, one of which occurred when Private Hodges was wrestling and fell on his injured knee. After several more months at Satterlee and an attack of facial erysipelas, Private Hodges returned to his regiment in March of 1864. Despite surviving his wound, Private Hodges of the 7th MI was killed at the Battle of the Wilderness, 2 months after returning to his regiment.

One case of a soldier treated at Satterlee for wounds received at Cold Harbor was described as “gunshot wound of the lower extremity and genital organs; the ball entering the scrotum and destroying the left testicle, passed onward, entering the upper third of the right thigh on the internal side, and coming out on the posterior and internal aspect of the same…”[8] The soldier, Private H. D. (full name not recorded) of the 45th PA, returned to duty in early January of 1865 before being discharged in May of that same year.

After the war ended, patients were discharged or moved to other hospitals and the once filled wards of Satterlee were empty. Over 50,000 soldiers received treatment within the wards of Satterlee, the hospital was essentially a small city. Satterlee housed many different services for doctors and patients such as a barber shop, dispensary, library, post office, and its own newspaper, The Hospital Register. There was no need for a massive hospital complex anymore as city hospitals became the standard. Satterlee closed its doors in August of 1865 and was demolished several years later in 1869. Today, the only remnants of the once famed Satterlee Hospital are in Clark Park, near a residential section of Philadelphia, where a historical marker tells a fraction of the story.

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021. He is currently pursuing a Masters in American History from Gettysburg College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute.

Sources

[1] “Satterlee General Hospital.” American Battlefield Trust, August 24, 2021. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/satterlee-general-hospital?ms=imargtegqnnstfvg.

[2] Ujifusa, Steven. “West Philadelphia’s Satterlee Hospital (Part I).” PhillyHistory Blog, November 3, 2016. https://blog.phillyhistory.org/index.php/2016/11/west-philadelphias-satterlee-hospital-part-i/.

[3] Ujifusa, Steven. “West Philadelphia’s Satterlee Hospital (Part I).” PhillyHistory Blog, November 3, 2016. https://blog.phillyhistory.org/index.php/2016/11/west-philadelphias-satterlee-hospital-part-i/.

[4] Holland, Mary Gardner. Our Army Nurses: Stories from Women in the Civil War. Roseville, MN: Edinborough Press, 2009. Pg 127-128

[5] Holland, Mary Gardner. Our Army Nurses: Stories from Women in the Civil War. Roseville, MN: Edinborough Press, 2009. Pg 129

[6] The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Vol. 2. Pt 1. Washington: G.P.O., 1888. Pg. 173

[7] The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Vol. 2. Pt 3. Washington: G.P.O., 1888. Pg. 364

[8] The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Vol. 2. Pt 2. Washington: G.P.O., 1888. Pg. 406