Table of Contents

Prostitution is the practice of engaging in indiscriminate sexual activity with strangers in exchange for payment.[1] It has existed since ancient times and appears to be a permanent fixture in society despite efforts to eradicate and criminalize it. Despite a push to change the word prostitute to sex worker to shed the negative connotations associated with it, the act of selling sex remains extremely controversial.[2] What did our Victorian forebears think of sex and prostitution? They certainly knew it existed and took part in sex (how else would any of us be here?) but their outlook on sex, chastity and prostitution depended on several social factors.

Victorian attitudes towards sex varied by class and gender. The upper class upheld the sexual purity of women, believing sex only existed for them within the confines of marriage. Upper class men, however, were given more sexual freedom and allowed the luxury of engaging in both pre and extramarital sex. Lower class Victorians, however, did not have the luxury of such attitudes. First and foremost, their lives revolved around survival. Families lived in crowded one room dwellings, worked long, hard hours and barely eked out a living from their wages. Living in such close quarters meant family members invariably saw one another naked, and children often shared a bed with their parents when siblings were conceived.

Victorian society viewed prostitution largely the same as we do today, with strong disapproval but also with a level of sympathy. Victorians understood that morally corrupt men and poverty could drive a woman to a life of prostitution, while others believed prostitutes helped protect morally pure women from men’s lascivious and uncontrolled passions. This belief carried over into the miliary during the Civil War as many officials believed prostitutes served as an outlet for soldier’s frustrations (not to mention pent up sexual energy) thus protecting respectable women.

What would compel a woman to choose a life of prostitution? Put simply, destitution and starvation. During the 19th century, a woman’s economic status was totally dependent upon a man. Should he die or abandon her, she had few options. Jobs available to women were very limited and paid poorly. In 1858, Dr. William Sanger of the Venereal Diseases Hospital on New York’s Blackwell’s Island surveyed 2,000 white female prostitutes and found overall they were between 18 and 23 years of age, foreign, unmarried, had a child, came from a poor working-class family and had experienced economic hardships. Sanger also found that a quarter were married and nearly half had worked as domestic servants. The most common reasons given for taking up the sex trade were destitution, inclination and being seduced and abandoned. [3]

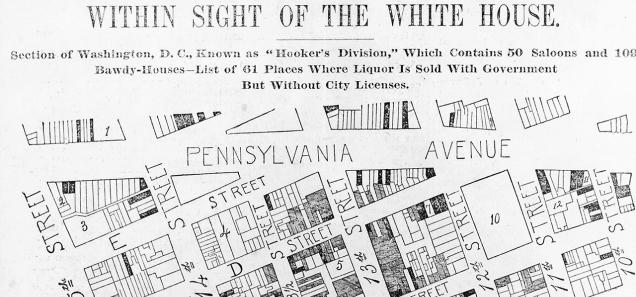

When the Civil War erupted, prostitution flourished near army camps and cities like Richmond, Washington DC and Nashville where armies were stationed. In Nashville, prostitution jumped 75% – from 200 in 1860 to 1,500 in 1862[4]. Washington D.C. housed around 500 houses of ill fame and public disturbances became so great that Union General Joseph Hooker moved all lower-class brothel workers into an area known as Murder Bay, which is the Federal Triangle today. The area became known as “Hooker’s Division.” Though Hooker is often credited with coining the term, it predates the Civil War and was used as far back as 1845.[5] It should be noted that with so many men away at war, many lower-class women turned to prostitution to put food on the table.

By far the most devastating effect of rampant unprotected sex with prostitutes by married and unmarried soldiers alike was the spread of venereal disease. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion claimed the cause of these diseases were “intemperance [and] the conditions which favored their causation.” Among white troops there were 73,382 cases of syphilis and 109,397 cases of gonorrhea and gonorrheal orchitis (swelling of the testicles) for total of 82 cases annually per thousand men. African American troops fared better, having 33.8 cases of syphilis and 43.9 cases of gonorrhea per one thousand men annually.[6]

Treatments for these diseases included many different compounds such as the ever-prevalent mercury, potassium iodide in a syrup of sarsaparilla, copaiba balsam, powdered cubebs, magnesia, black or yellow wash and silver nitrate. Surgeon William R. Blakeslee with the 115th PA reported that he effectively treated gonorrhea by “injecting [into the urethra] a solution of chlorate of potash … every hour for twelve successive hours, and then gradually ceasing its use during the next two or three days.”[7]

Surgeon Ezra Read of the 21st Indiana treated venereal diseases with “mercurial fumigation, which deposits the mercury upon the surface of the body when in a state of perspiration induced by the heated vapor of water surrounding the patient confined in a close and air-tight bath.” He asserted this method of treatment “eradicates the disease in a shorter period of time than is required by the internal use of mercury.”[8]

Assistant Surgeon Warren Webster wrote of his “unwavering belief in the efficacy of the mercurial treatment in syphilitic complaints.” He theorized that “the virus must work in the tissues about the surface during four or five days before it is sufficiently elaborated to affect the system of the blood. If, during this time, the sore should slough … the poison is destroyed or removed before it is ripe, and we need not administer mercury.” However, “if the sore has not been destroyed or has not sloughed away, the poison has been carried by the absorbents to the glands of the groin. These inflame and suppurate, and with the pus the poison is discharged and does not further affect the system. In such a case we need not, I think, prescribe mercury.”[9]

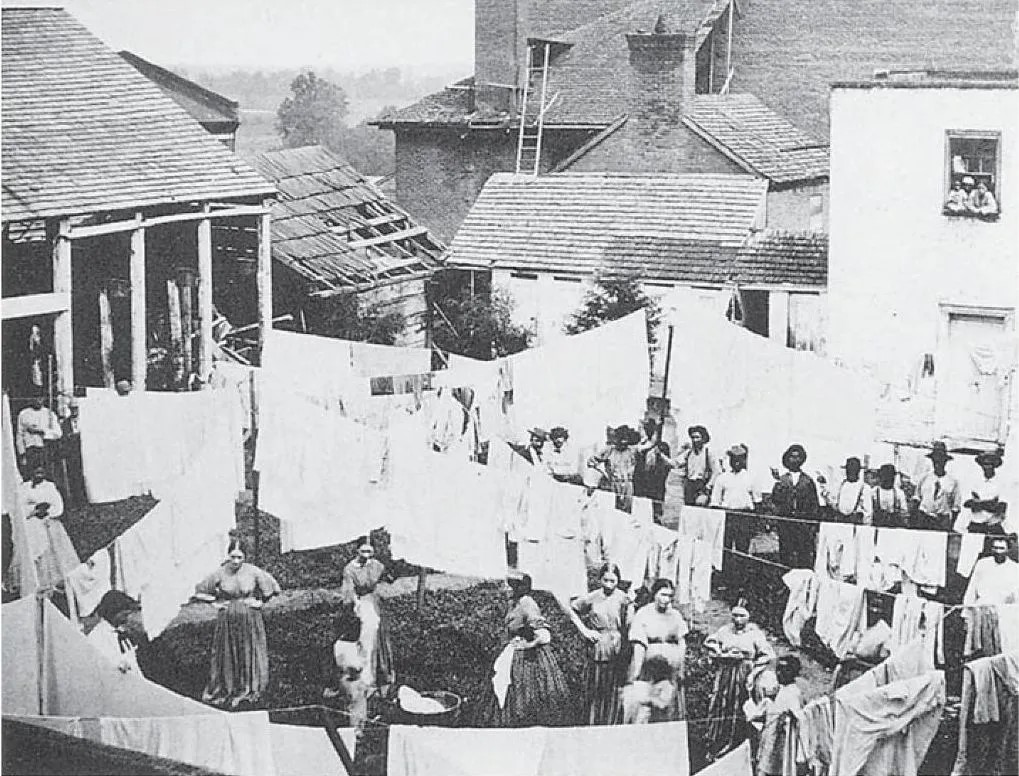

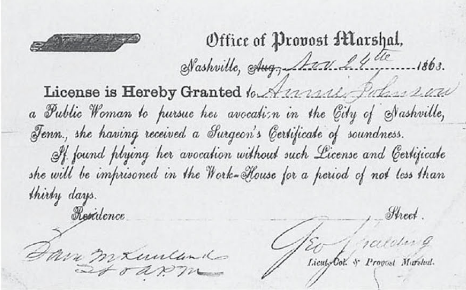

Venereal disease debilitated so many regiments that officials in Nashville, Tennessee decided to regulate the sex trade. After General William Rosecrans failed to forcibly remove all prostitutes from the city, officials began an initiative that evaluated the health of prostitutes and provided those deemed free of disease with a license to legally ply their trade.

Under orders issued by Provost Marshall George Spalding on August 1, 1863, all public women were required to register, pay one dollar for weekly examinations and receive tickets of good health to work. Those found to be sick with venereal disease were sent to a hospital established solely for their care, with a weekly tax of fifty cents to defray the cost of treatment. Those women found plying their trade without a license would be “at once arrested and incarcerated in the workhouse for a period of no less than thirty days.”[10] Memphis quickly adopted a similar program.

Under this system, instances of venereal disease dropped dramatically, and those found suffering from venereal diseases (at least outwardly) did receive treatment. However, it must be said the pathology of venereal diseases remained unknown during this time, and the measures taken to treat, much less cure, them were largely unsuccessful.

Nashville’s Provisional Mayor Channing Richards submitted a report on February 11, 1865, stating in part “I shall certainly regret the abandonment of the system, for the result of my own observation has been decidedly favorable to it … I see many advantages to recommend it, for while it does not encourage vice it prevents to a considerable extent its worst consequences.”[11] With the end of the war, however, also came the end of this regulation which allowed for the rampant spread of venereal diseases once again.

Unfortunately, no effective treatment existed for bacterial venereal diseases, including gonorrhea and syphilis until the 20th century with the introduction of antibiotics. Prior to this, as we have seen, treatments were largely ineffective and nearly as devastating as the disease. It is unfortunate that those forced to turn to sex work had to face not only ineffective treatment but also the physical and psychological dangers of the profession as well. Prostitution remains just as prevalent today as in the 19th century, with no real consensus on how to approach the reality that most of those who turn to this profession do so for the sole reason of survival.

About the Author

Rachel Moses is the Collections Manager for the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. She received her MA in History in 2007 from Youngstown State University, where she focused on women’s history. She is a contributing author to Clara Barton Civil War Humanitarian and is co-leader of NMCWM’s Between the Lines Book Club.

Sources

[1] https://www.britannica.com/topic/prostitution

[2] https://inews.co.uk/opinion/columnists/sex-workers-prostitutes-words-matter-95447

[3] William W. Sanger, The History of Prostitution. (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1858), 484-523, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/41873/41873-h/41873-h.htm#Page_484.

[4] https://www.history.com/news/civil-war-prostitution-nashville

[5] Elizabeth A. Topping, What’s a Poor Girl To Do? Prostitution in Mid-Nineteenth Century America. (Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications. 2001), 43-44.

[6] Charles Smart, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, Part III Vol. I (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1888), 891.

[7] Ibid, 891-892.

[8] Ibid, 892.

[9] Ibid, 893.

[10] Ibid, 893.

[11] Ibid, 895.