Table of Contents

On a landscape scarred by the shot and shell of battle, a renowned surgeon from Massachusetts went to work surrounded by blood and gore. The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House raged with ferocity seldom seen, even when matched against other bloody contests of the Civil War. In this hellish landscape, Dr. William T.G. Morton provided mercy to those torn apart by bullets and shells, utilizing ether as an anesthetic, a revolutionary technique that Morton himself had devised in 1846, ushering in the birth of modern surgery.

Now in a makeshift field hospital in central Virginia, he used his experience as the original anesthetist to care for dozens of soldiers requiring capital operations – amputations.

Morton’s innovative use of ether as an anesthetic in the 1840s allowed the advent of modern surgical techniques. Gone were the days of speed as an integral part of the surgeon’s job description. Careful, precise surgical operations became the norm as anesthetic was adapted by doctor’s around the world in the 1850s. By the time of the Civil War, the use of ether and chloroform in surgery by American doctors was nearly universal. During the conflict, more than 95% of surgeries completed were done so under the use of anesthesia.

The founder of the anesthetic revolution went to the battlefield himself alongside other volunteer surgeons in May 1864, assisting military surgeons during the Battle of the Wilderness. When the armies moved south through burning woods toward a crossroads hamlet known as Spotsylvania Court House, the volunteers followed.

Known as the Overland Campaign, this continual fight started on May 5, 1864 and did not abate until the armies went into fortifications near Petersburg, Virginia in the middle of June. All the while, Union and Confederate forces faced off in a series of brutal battles, fought amid earthworks and field fortifications, swamps and woodlots.

Over the course of six weeks of combat, more than 80,000 men were killed, wounded, captured, or went missing. The startling toll in wounded left Union military medical professionals desperate for assistance, even though they were well-prepared with supplies and a well-functioning ambulance system, with a hospital system organized in nearby Fredericksburg.

Dr. Morton’s involvement at Spotsylvania is incredible. The innovator who first utilized ether as an anesthetic more 15 years earlier, brought his techniques personally to wounded soldiers on the battlefield. He quickly found work in the hospitals near Spotsylvania Court House as fighting there raged between May 8 and May 21. The battle concentrated on a string of Confederate earthworks atop a low ridge, known to history as the “Muleshoe Salient.” Every inch of ground saw men tumble, with bodies penetrated by Minie balls or shell fragments. Others were clubbed to death, bayoneted, or blown apart in combat at close quarters. Surgeons were left to attempt to put the pieces back together as best they could. Dr. Morton found his place at the head of the operating table, administering anesthesia to the wounded before surgery began.

A reporter for the Associated Press filed a story in late May that depicted Dr. Morton’s work in the field hospitals near Spotsylvania, shortly after ambulances carrying wounded Confederates arrived at the field hospital. The account provides valuable evidence, demonstrating the near universal use of anesthetic on the battlefields of the Civil War:

Dr. Morton, of Boston, one of the first discoverers, if not indeed the first discoverer of the anaesthetic properties of ether, has been with the army the last week, working and observing in his capacity, with all his might. During this time he has, with his own hands, administered ether in over 2,000 cases. The medical director, when asked yesterday in what operations he required ether to be used, replied, “In every case.” Day before yesterday some 300 rebel wounded fell into our hands. Of these twenty-one require capital operations. They were placed in a row, a slip of paper pinned to each man’s coat collar telling the nature of the operation that had been decided upon. Dr. Morton passes along, and with a towel saturated with ether puts every man beyond consciousness and pain. The operating surgeon follows and rapidly and skillfully amputates a leg or an arm, as the case may be, till the twenty-one have been subjected to the knife and saw without one twinge of pain. A second surgeon ties up the arteries; a third dresses the wounds. The men are taken to tents near by, and wake to find themselves cut in two without torture, while a winnow of lopped off members attest the work. The last man had been operated upon before the first awakened. Nothing could be more dramatic, and nothing could more perfectly demonstrate the value of anaesthetics. Besides, men fight better when they know that torture does not follow a wound, and numberless lives are saved that the shock of the knife would lose to their friends and the country.

Morton himself wrote to a friend to describe his experiences near the battlefield in May 1864. His highly descriptive letter includes numerous aspects of his visit, including his use of anesthesia, the good work of the ambulance corps, the nature of combat during the Overland Campaign, and the sight of black refugees fleeing north toward Union-controlled territory. The letter was found in the Physicians and Surgeons of America¸ published in 1896.

HEADQUARTERs, May 19, 1864.

My Dear :—Soon after leaving Fredericksburg to come out here, we passed some four or five army wagons parked, each one with its four or six horses or mules, ready for service, yet near the supplies of forage. There were also large droves of cattle, brought from the western states for the use of the army, and killed as they are needed. The road, if road it may be called, was wretched indeed, the horses often sinking in mud-holes to the saddle-girths. Through this, ambulances and wagons were floundering along, carrying the wounded to Fredericksburg, while others, only slightly injured, plodded along on foot. Occasionally we passed an impromptu camp, where these slightly wounded men had stopped to rest, and several newly made graves showed where some poor fellows had made their last halt. The last five miles of our journey was over a new road cut through the woods, as the guerrillas had possession of the turnpike near Spotsylvania Court house. Indeed they have occasionally swooped in upon the road over which we went, carrying off horses and robbing the wounded.

On reaching the top of an eminence, I at last saw our line, in the shape of a horseshoe, somewhat straightened out, with troops all around, in readiness for instant attack, while beyond them, crouched in rifle-pits, were our pickets. Riding through regiments and batteries I reached a house which had been pointed out to me as Gen. Grant’s headquarters, but found on my arrival that he had moved, that the building might be used as a hospital. Just then several wounded rebels, were brought up on stretchers, and the surgeon in charge, who had known me after Burnside’s attack upon Chancellorsville, invited me to administer anaesthetics, which I did. All of them had limbs amputated, and seemed very grateful afterwards for the kind treatment which they received, but they were bitterly secesh when the war was alluded to.

When these wounded rebels had been attended to, the surgeon sent an orderly with me to the headquarters of the medical director of the Army of the Potomac, to whom I reported for duty, and then, as there was no need for my services, I went on until I reached the headquarters of the army. These occupied a group of about twenty tents, pitched along the border of a piece of woodland. In front of one of these tents, the fly of which was converted into an awning, sat the lieutenant general, with several officers and Mr. Dana, the assistant secretary of war.

While Gen. Grant was in Washington I had been introduced to him, and he now remembered me and kindly welcomed me. He conversed very frankly upon military matters, declaring that he intended to give the rebels all the fighting they wanted. It would not be proper, I suppose, to write you the general’s remarks on the campaign, but I must tell you that in answer to my question—“How long is this deadly conflict to last?” he replied, in his cool, unassuming way, “Perhaps until the Fourth of July, and we shall have all the time supplies and reinforcements, which they can’t get.”

The general assigned me a tent and an orderly, and invited me to share his camp fare. On previous visits to camps, I had found that the generals lived far better than do the boarders at the Washington hotels, but our supper that night was simply coffee and bread and butter. The butter (the general said) was made on the field of battle.

Since I have been here there has been a succession of skirmishes and picket firings. The pickets lie crouched in rifle-pits, in which when it rains, there is often a foot or eighteen inches of water, and between them is what is called the disputed ground. When there is any heavy firing heard the ambulance corps, with its attendants, stationed nearest to the scene of action, starts for the wounded. The ambulances are halted near by, and the attendants go in with stretchers, to bring out the wounded. The rebels do not generally fire upon those wearing the ambulance badges.

Upon the arrival of a train of ambulances at a field hospital the wounds are hastily examined, and those who can bear the journey are sent at once to Fredericksburg. The nature of the operations to be performed upon the others is then decided upon, and noted on a bit of paper pinned to the pillow or roll of blanket under each patient’s head. When this had been done I prepared the patients for the knife, producing perfect anaesthesia in an average time of three minutes, and the operators followed, performing their operations with dexterous skill, while the dressers in their turn bound up the stumps. It is surprising to see with what dexterity and rapidity surgical operations are performed by scores in about the same time really taken up with one case in peaceful regions.

The medical department deserves great credit for the abundant supplies sent to the wounded, while the members of the Christian and sanitary commissions furnish many additional comforts. The number of wounded has been greatly exaggerated, and will not to-day amount to twenty thousand. Of this number a large proportion are so slightly wounded that in thirty days they will be ready for duty again.

The dead are buried where they fall, or near the hospitals in which they die. Their names are carefully written on wooden head boards, and entered into registers. It is, however, useless for friends to come here for their remains, as there is no way of transporting them to Washington except in government wagons, and the army needs all its transportation.

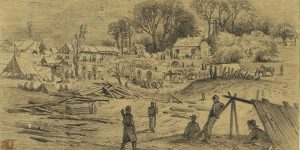

What houses remain standing are used as hospitals, the female occupants being permitted to retain one room. Often a stack of chimneys show where a dwelling has been burned. The colored people are leaving for the North, carrying their effects in small wagons or carts, often drawn by an ox working in shafts. It has rained nearly every § since I have been here, but the soldiers manage to keep themselves comfortable under shelter tents or bowers. Artillerymen sleep under their cannon, which are covered by tarpaulins.

Very truly yours, W. T. G. MORTON.

Learn more in this interview with Jake Wynn, the post’s author

About the Author

Jake Wynn is the Director of Interpretation at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He also writes independently at the Wynning History blog.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.