Table of Contents

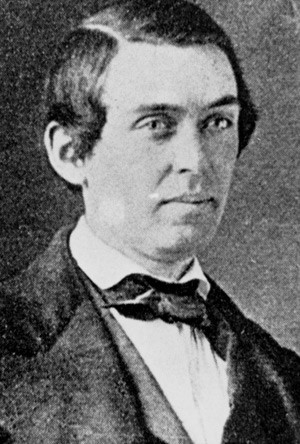

Dr. Edward R. Squibb was born in Wilmington, Delaware on the 4th of July in 1819. At an early age, Squibb dreamed of becoming a doctor, and his first step to doing so was to become an apprentice druggist. This experience allowed him to pay his way through medical school at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia where he excelled in the eyes of his professors. After graduating in 1845, Squibb received a position at the college as the Assistant Demonstrator of Anatomy, Curator of the Museum, and Clerk of the Clinic.

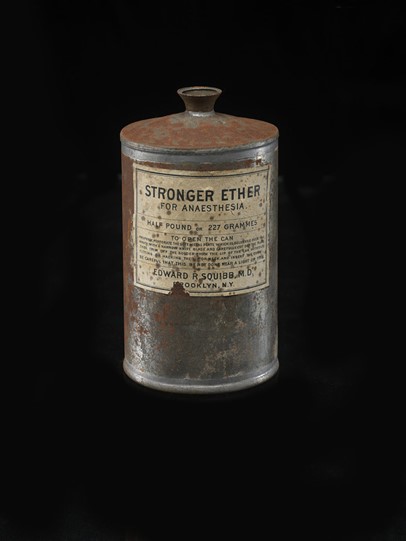

In 1847, after his tenure at the college, Squibb joined the US Navy and was assigned to the US Brig, Perry, which patrolled the waters of the Caribbean and South Atlantic disrupting South American slave trading, “he saw active sea service for four years, and became, as he often said, very tired of having so little to do.”[1] This boredom would not last and in 1852 he was transferred to the Naval hospital in Brooklyn, New York where he worked alongside Dr. Benjamin Franklin Bache. Later that same year, the Naval hospital established a pharmaceutical laboratory with Dr. Bache as the Director and Dr. Squibb as the Assistant Director. The two achieved great advancements in manufacturing anesthetic ether in a more efficient and safe manner by using steam instead of an open flame to distill the drug. This device increased the quality of ether just in time for the outbreak of the Civil War.[2]

In 1857, Dr. Squibb left the Navy to set up his own private pharmaceutical laboratory in Brooklyn. From his laboratory in the city, Dr. Squibb was able to continue manufacturing ether while also producing various other medicines for the US Army. Dr. Squibb acquired “the four-story brick building, No. 149 Furman Street, Brooklyn… and Dr. Squibb at last found himself in the position towards which he had been looking forward for many years.”[3] He ran a successful operation for over a year until Christmas Eve in 1858.

A fire broke out in the laboratory while Dr. Squibb was distilling some ether. While the method was much safer than previous distillation methods, ether was still incredibly volatile. Dr. Squibb was injured in the fire, receiving burns to his hands and face but both he and his laboratory fully recovered. Soon enough, he was back to work making medicines and advocating for regulations within the medical community to make sure that medicines were safe for public use and consumption.

The medical supply chain was a tricky business, and one needed be a skilled pharmacist in order to thrive. In the 19th century, pharmacists acted as drug manufacturers, distributors, and physicians. They wore many different hats, but their most important one was as medical purveyor.

The role of a purveyor was to acquire the raw materials for medicines to be used in the manufacturing process. Medical purveyors and medical chemists would encounter problems where “drug merchants commonly tried to increase their profits by adulterating their offerings. Packages of opium, for example, were often weighed down with stones or bullets. Belladonna leaves were cut with cheaper matter, such as digitalis leaves.”[4] There was no concrete system of regulation and standardization among medical supplies until later in the 19th century. While serving as a Naval surgeon, Dr. Squibb was passionate about making sure the drugs he administered were of the highest quality possible. Dr. Squibb became one of the doctors leading the charge in the creation of “quality control” laws and regulations beginning in 1860.

During the Civil War, Dr. Squibb’s laboratory was able to manufacture enough medicine to supply one-twelfth of the army’s medical stores. Dr. Squibb and many other private medicinal manufacturers were able to supply most of what the Army needed. However, it soon became apparent that more medicines were needed than could be manufactured. The federal government set up their own laboratories to fill the gaps private businesses could not and supplemented their work to increase the amount of medicines being produced as a whole.[5]

Purveyors had a few ways of acquiring the materials to manufacture medicines during the war. Often, they would buy directly from distributors or from local sources if the normal chain were interrupted. The purveyors would then resell the materials to Army laboratories such as the one operated by Dr. Squibb to be packaged and distributed to hospitals and regimental surgeons across the country.[6] The Union had more access to raw materials to manufacture medicines and were thus able to produce more than Confederate medical laboratories.

Because of the Federal blockade of the South, raw materials had an incredibly tough time reaching Confederate shores. One of the main methods of acquiring medicines was blockade running. Ships of many sizes would load up with Southern cotton and attempt to evade General Winfield Scott’s brainchild of a blockade and sail to various Caribbean nations to trade goods. The top items requested by the Confederacy were weapons, clothing, and medicine. Confederates would also raid Union medical supplies if they captured a Union position looking for quality medicines. Some of Dr. Squibb’s medicines even wound up in the stores of Confederate surgeons.[7]

In addition to manufacturing medicines, Dr. Squibb invented his own version of a medical chest called the Squibb medical chest. It was a wooden chest designed to be portable and fit an array of medicines. Just about anything a surgeon could need on the march or in a field dressing station could fit inside the chest. The Squibb medical chest, along with all of the other inventions and medicines that Dr. Squibb created were never patented because “Squibb held onto the notion that anyone who wished to use them to benefit mankind should have the ability.”[8]

Dr. Squibb became a successful businessman, purveyor, and manufacturer and was able to use his wartime experience to formally create his own drug manufacturing and distribution company, the Squibb Corporation. Several decades after the war, Dr. Squibb’s sons entered the family business, and the name was changed to Squibb & Sons. Edward Squibb used this platform to influence change in the medicinal community. In 1879, Squibb proposed a law in order to prevent the alteration and adulteration of food and medicines to the New York State Medical Society. His ideas were not signed into law until after his death and what was known as the Squibb Bill was used to inspire the Food and Drug Act of 1906.[9] Dr. Edward Squibb’s company still exists today and continues to manufacture various drugs and medicines.

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021. He is currently pursuing a Masters in American History from Gettysburg College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute.

Sources

[1] Remington, Joseph P. 1901. “EDWARD ROBINSON SQUIBB, M.D.” American Journal of Pharmacy (1835-1907): 14, http://ezpro.cc.gettysburg.edu:2048/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/edward-robinson-squibb-m-d/docview/89694407/se-2. Pg 3

[2] “Squibb, Edward Robinson (1819-1900).” Reynolds-Finley Historical Library. University of Alabama at Birmingham, n.d. https://library.uab.edu/locations/reynolds/collections/civil-war/medical-figures/edward-robinson-squibb.

[3] Remington, Joseph P. 1901. “EDWARD ROBINSON SQUIBB, M.D.” American Journal of Pharmacy (1835-1907): 14, http://ezpro.cc.gettysburg.edu:2048/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/edward-robinson-squibb-m-d/docview/89694407/se-2. Pg 4

[4] Hasegawa, Guy R. “Pharmacy in the American Civil War.” American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 57, no. 5 (2000): 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/57.5.475. Pg 68

[5] “Squibb, Edward Robinson (1819-1900).” Reynolds-Finley Historical Library. University of Alabama at Birmingham, n.d. https://library.uab.edu/locations/reynolds/collections/civil-war/medical-figures/edward-robinson-squibb.

[6] Hasegawa, Guy R. “Pharmacy in the American Civil War.” American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 57, no. 5 (2000): 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/57.5.475. Pg 70

[7] Hasegawa, Guy R. “Pharmacy in the American Civil War.” American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 57, no. 5 (2000): 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/57.5.475. Pg 70

[8] “Squibb, Edward Robinson (1819-1900).” Reynolds-Finley Historical Library. University of Alabama at Birmingham, n.d. https://library.uab.edu/locations/reynolds/collections/civil-war/medical-figures/edward-robinson-squibb.

[9] “Company History Timeline – Bristol Myers Squibb.” bms, August 25, 2021. https://www.bms.com/about-us/our-company/history-timeline.html.