Table of Contents

Tourniquets are an essential tool in the kit of today’s combat medics and first responders. These professionals are trained in the proper use and deployment of the CAT (Combat Application Tourniquet) to give the victim the best possible chance of survival. While the CAT is a modern device, tourniquets have been documented since 600 BCE in India. Tourniquets were widely used in surgical procedures and in battlefield conditions ever since then. The ancient tourniquets were a few simple strips of leather with no mechanism to tighten and secure the tourniquet.

It was not until the 16th and 17th centuries that physicians developed a method of using a stick to tighten the tourniquet around the limb. In 1718, French physician Jean-Louis Petit invented a new style of tourniquet and was the first to use “tourniquet” in the name of his device. The “Petit Tourniquet” became the preferred style of surgical and battlefield hemorrhage control for almost 200 years.[1]

During the Civil War, the Petit Tourniquet was one of the most common and effective tourniquets available. U.S. Army surgical kits included a tourniquet and their applied use in surgical procedures was part of a medical student’s education. According to the Handbook of Surgical Operations, a tourniquet’s purpose was “an instrument designed to make such pressure over an artery, at some point in its course, as to control the circulation.”[2]

While the Petit, or screw, tourniquet was the preferred, and most effective way of hemorrhage control, surgeons would instruct soldiers on how to apply a field tourniquet if needed. By applying a tourniquet in the field, it has greater potential to save a soldier’s life by controlling the bleeding as soon as possible. Dr. Samuel Gross, one of the nation’s top surgeons, wrote in his Manual of Military Surgery that “it is not necessary that the common soldier should carry Petit’s tourniquet, but every one may put into his pocket a stick of wood, six inches long, and a handkerchief or piece of roller with a thick compress, and be advised how, where, and when they are to be used.”[3] Dr. Gross also states that a fife, drumstick, knife, or ramrod could be used just as well as a stick. Even today, you can follow the advice of Dr. Gross–just a simple piece of cloth and a stick can save someone’s life in an emergency.

One soldier to benefit from the use of a tourniquet was Private B. Cunningham, Co. B, 51st Ohio Infantry. Private Cunningham, aged 21, was wounded at the Battle of Stone’s River by a rifle ball that entered the middle of his thigh, deflected downward and out the back of the same thigh. Understandably, there was quite a lot of bleeding from the wound which was controlled using a tourniquet. Due to the path the ball took, the ball severed a nerve in his leg, causing a permanent disability.[4] However, Private Cunningham’s life was saved without the need for amputation using a tourniquet.

Private W. Sobbee, Co. G, 61st Pennsylvania Infantry was wounded during the Battle of Fort Stevens in July of 1864. Private Sobbee was shot in the arm during the battle and a field tourniquet was applied to the wounded arm. The quick action in the application of a hemorrhage control device saved Private Sobbee’s life and he was able to make a full recovery, with the pension board later noting that there was a very weak pulse in his arm and his hand became numb in cold weather.[5]

While most wounding occurred on the battlefield, accidents do happen. Corporal E. Hacket, Co. A, 1st Pennsylvania Infantry had a bayonet puncture his right thigh while taking part in drill near Camp Whipple in Philadelphia. When he was brought to the surgeon, he had reportedly lost about 12 ounces of blood before a tourniquet was applied and kept on for three days. Two days after the removal of the tourniquet, Corporal Hacket was returned to duty with no ill effects.[6]

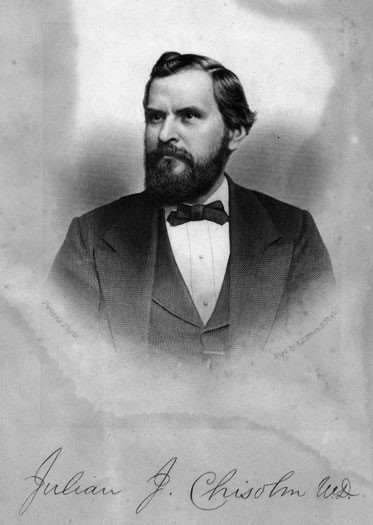

Despite the documented effectiveness of the tourniquet in use by Union surgeons, many surgeons in the Confederate medical department believed that tourniquets did more harm than good. Many saw them as too restricting by not letting blood flow, which caused the need for amputation or would cause infection. One of these doctors was John J. Chisholm, one of the best doctors in the South. Dr. Chisholm wrote “should the soldier have a large artery wound, and the hemorrhage be excessive, which is but seldom the case, the surgeon should instruct the orderly who superintends his transportation, how to make judicious finger pressure. This is much better than the tourniquet, producing much less engorgement of the injured tissues.”[7]

The debate over the effective use of the tourniquet continued into the 20th century. While the benefits of applying a tourniquet far outweigh the detriments, there is still some risk to even the correct application of the tourniquet. If left on for too long, the limb could begin to die due to lack of blood flow. However, despite the risks, when a tourniquet is applied properly, there is a much higher chance the wounded person will live.

For more detailed information, you can take a course called “Stop the Bleed” which will give you the proper training in the application and use of a tourniquet. The “Stop the Bleed” program is the civilian application of the Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) initiative created by retired Navy SEAL Captain Dr. Frank Butler.

Tourniquets have been used by soldiers on the battlefield and surgeons in the operating room for centuries. They have the potential to save someone’s life, or they can keep the surgical field clear of blood, reducing the chances of a surgical error. Tourniquets are a vital piece of lifesaving equipment today, just as they were in the Civil War. While the CAT is more advanced than the Petit, their objective has not changed: to save lives.

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021.

Sources

[1] Saied, Alireza, Mousavi, Alia A., Arabnejad, Fateme, and Afshin A. Heshmati. “Tourniquet in Surgery of the Limbs: A Review of History, Types and Complications.” Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal 17, no. 2 (2015).

[2] Smith, Stephen. Handbook of Surgical Operations. Baillière Brothers, 1862. Pg 26-27

[3] Gross, Samuel. A Manual of Military Surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott, 1862. Pg 53

[4] Barnes, Joseph. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Vol. 2 Part 2. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1875. Pg 339

[5] Ibid. Pg 445

[6] Barnes, Joseph. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Vol. 2 Part 3. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1875. Pg 6

[7] Chisolm, John Julian. A Manual of Military Surgery, for the Use of Surgeons in the Confederate Medical Department. 2nd ed. Richmond, VA: West & Johnson, 1862. Pg 149