Table of Contents

In 1811, towards the end of the Napoleonic Wars, France found itself in dire need of gunpowder. Bernard Courtois, a French chemist, was experimenting with using seaweed as an alternative way of processing gunpowder, when he made an amazing discovery. He added too much acid to the suspension of seaweed ash, which produced a violet-colored vapor. After the vapor had condensed into crystals, Courtois analyzed them and then gave some of them to a fellow chemist, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, for further study.

Two years later, Gay-Lussac presented his study to the scientific community, announcing the discovery of a new element that he named “iodine,” after the Greek word “ioeides” meaning violet colored. While he acknowledged Courtois as the original discoverer of the element, Gay-Lussac was the first to recognize iodine as a totally new substance.

A Swiss physician by the name of J.F. Coindet had previously used burnt sponge and seaweed for the treatment of goiter (an enlargement of the thyroid gland). This treatment had been in use since 3600 B.C., when it appeared in Chinese medical writings, as well as writings by the Greek physician Hippocrates. Upon hearing of the work of Courtois and Gay-Lussac, Coindet suspected that iodine might be the active ingredient in seaweed that cured goiter. In 1819, he successfully tested a tincture of iodine on 150 patients, significantly reducing the size of their goiter within one week.

As a result of these early studies, in the 1830s the medical community started advocating for iodine supplements to decrease the occurrence of goiter. French nutritional chemist Jean Baptiste Boussingault recommended that naturally iodized salt be distributed to the general public for consumption, and in 1852, Adolphe Chatin, a French chemist, published his study showing that iodine deficiency in the thyroid gland was the definite cause of goiter.

The benefits of iodine were not limited to internal use. The medical community soon discovered its effectiveness as a topical treatment for such afflictions as burns, acute inflammation, and chilblains. Even a byproduct of iodine proved an effective treatment. In 1826, Antoine Jerome Balard, a French apothecary and chemist, devised a method to measure iodine in seaweed and other plants. While developing this method, he accidentally discovered a byproduct, which he called “bromine.” This element would prove extremely effective in treating hospital gangrene, a major cause of mortality for soldiers during the American Civil War.

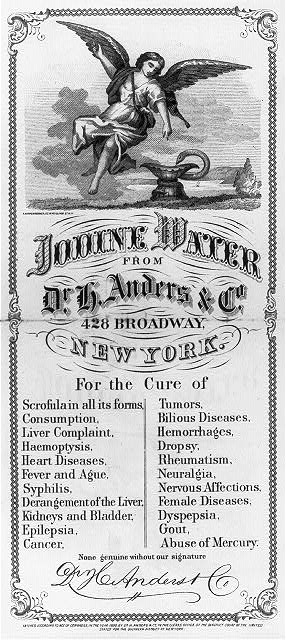

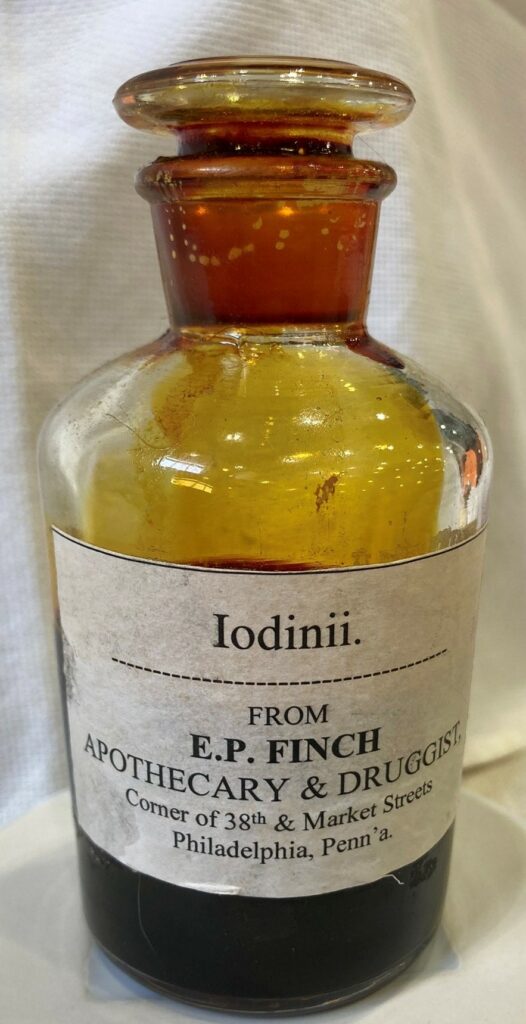

Physicians and surgeons quickly became enamored of iodine and its potential for treating a multitude of ills. The new substance was tested and tried for a huge variety of diseases and conditions. Tincture of iodine, or one of its forms, was applied to almost every type of case that otherwise resisted ordinary medicines. Between 1820 and 1840, there were dozens of essays in medical journals that attested to the amazing benefits of the use of iodine both internally and externally. Pharmaceutical companies and private manufacturers advertised their iodine products as curing such conditions as heart disease, gout, cancer, syphilis, neuralgia, epilepsy, and tumors.

By the time of the start of the American Civil War in 1861, iodine and its byproduct bromine were considered essential medications to be used by military surgeons. While germ theory had not yet been widely accepted, physicians understood that these products could be used to prevent “mortification of the flesh.” The concept of an antiseptic was unknown at the time, but what doctors did realize was that application of iodine and bromine was successful in treating infections, although the reason for that effectiveness was unknown.

One example of the use of iodine during the Civil War comes from the memoirs of Confederate General John B. Gordon. At the battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, Gordon had been wounded five times. When he developed erysipelas (a bacterial infection of the upper layer of the skin) in his left arm, the doctors told his wife to paint the arm three to four times a day with iodine. Gordon’s wife complied with the doctor’s instructions by applying the iodine, in Gordon’s estimate, three to four hundred times a day. He credited the treatment with saving not only his arm, but his life as well.

The high demand during the Civil War for pharmaceutical products led to the growth of pharmacies as businesses. The U.S. Army never had its own manufacturing laboratory and instead contracted businesses, which after the war developed into large corporations. Some of the most well-known names in the pharmaceutical industry such as Pfizer and Squibb had their origins in wartime production. When Joseph Lister’s germ theory of bacterial infections began to gain acceptance in 1865, the use of antiseptics was promoted by these corporations—and iodine was one of the more common in use.

By 1890, there were 30 different medications derived from iodine that were promoted. By the early 1900s iodine was well-established as an antiseptic in medical and surgical practices. By 1928 there were 128 listed iodine items and in 1956, that number had risen to 1,700. Bernard Courtois could never have envisioned how his discovery would impact medical science. In 1822, eleven years after he discovered the strange violet-colored element, he went into manufacturing high-quality iodine and its salts. In 1831, he was awarded 6,000 francs as part of a prize from the French Royal Academy of Sciences for the medicinal value of his discovery. He struggled financially for the rest of his life and died at 62 years of age on September 27, 1838, leaving his wife and son destitute. Ironically, in his pursuit of a better way to make gunpowder, he had stumbled on a better way to save lives.

Sources

Abraham, Guy E., MD, The History of Iodine in Medicine Part I, www.optimox.com/iodine-study-14, 1999

Bernard Courtois, Wikipedia entry, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernard_Courtois

Clark-Emory, Carol, Three Plants from U.S. Civil War Medical Guide Fight Infection, www.futurity.org/civil-war-medical-guide-antiseptic-plants-2072202, May 28, 2019

Gordon, John B., Reminiscences of the Civil War, 1903

Leung, Angela M., Lewis Braverman, and Elizabeth Pearce, History of U.S. Iodine Fortification and Supplementation, published online by the National Center for Biotechnology Information, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Paciorek, Jessica, “Medicine and Its Practice During the American Civil War”, TCNJ Journal of Student Scholarship, Volume IX, April 2007

About the Author

Tracey McIntire earned her BA in English at Rivier College in Nashua, NH. She is Director of Communications at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, an interpretive volunteer at Antietam National Battlefield, and an active Civil War living historian, where she portrays a woman soldier in various guises.