Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

Never had Americans been forced to deal with the sheer scale of human carnage wrought by the Civil War. Hundreds of thousands lost their lives, and countless more were maimed. The overwhelming casualties drove Americans to rethink emergency medical response in many ways: the training of medical professionals, institutionalizing triage, and creating organized and independent ambulance services.

Major movements like these necessarily bring about innovation on a smaller scale. Someone must come up with new uniforms, ambulances, medicines, and stretchers. Throughout the Civil War, inventors patented and built numerous stretcher models for use by the new United States Ambulance Corps. All of them struggled with balancing strength, weight, and versatility. Below we explore some of the most prominent stretcher models: those that were widely used or the most creative in their approach.

The Satterlee

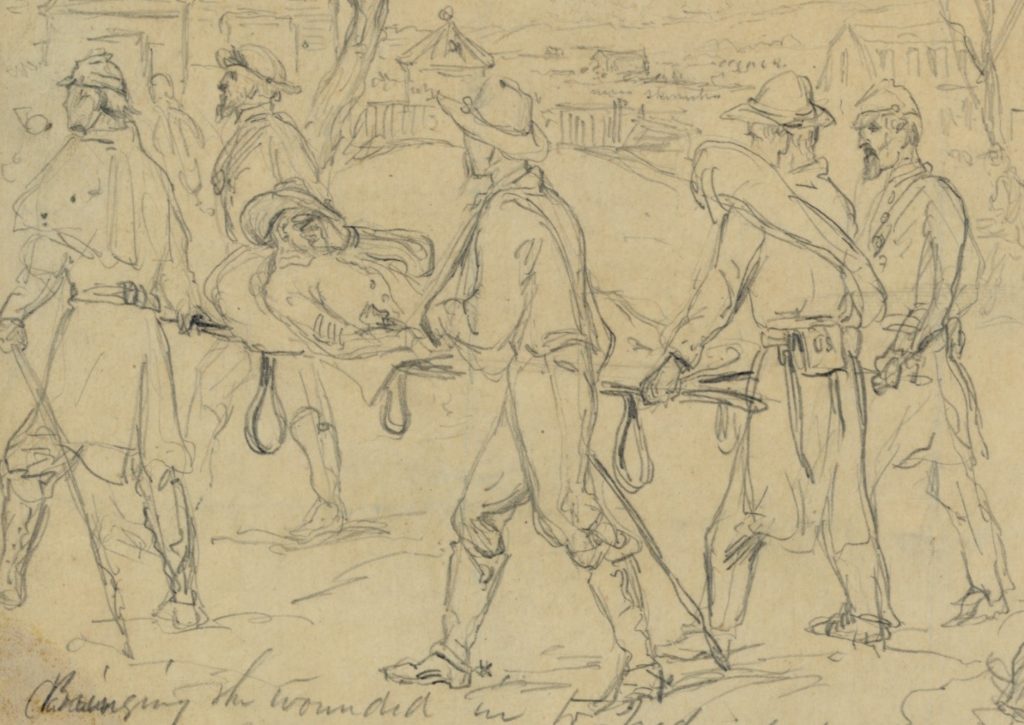

At the outbreak of war, the Satterlee was the standard issue stretcher of the United States Army. It was designed by Surgeon Richard S. Satterlee,[1] a career military medical professional who had served for decades in the US Army and saw service in Mexico. Below is a sketch of a probable Satterlee stretcher in use

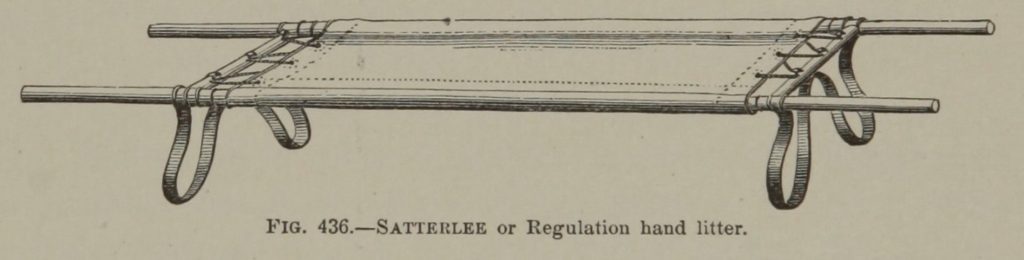

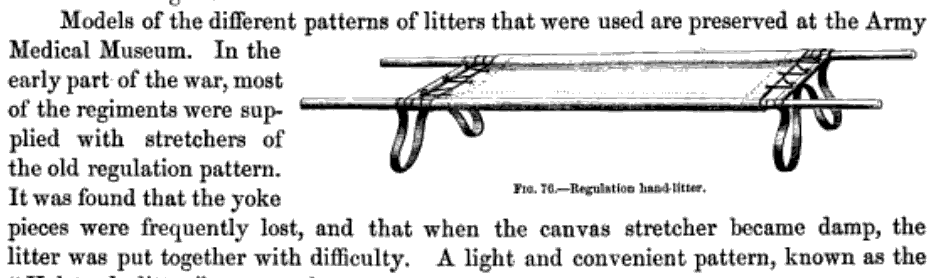

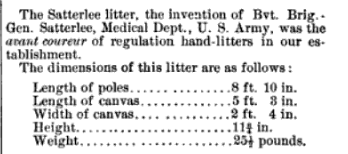

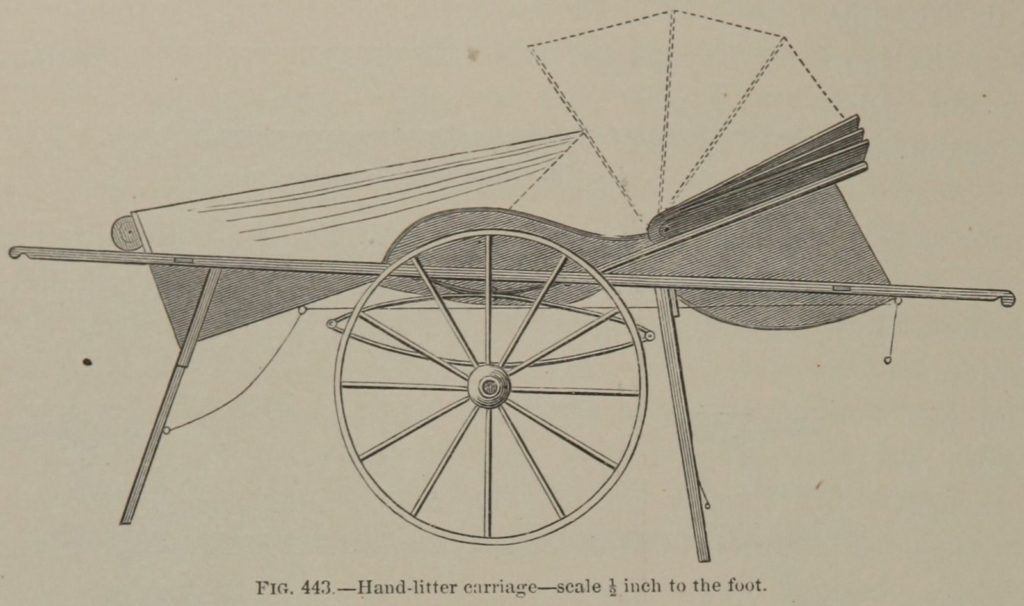

As the standard litter at the war’s outset, the Satterlee was widely available both North and South. It was the first stretcher model to receive attention in The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, which has an excellent chapter on the various models. The illustration below is from Volume II, Part III, page 926:

In preparing the massive Medical and Surgical History, the Surgeon General’s office prepared Circular No. 6 Reports on The Extent and Nature of the Materials Available for the Preparation of a Medical and Surgical History of the Rebellion. While the compilers did misidentify some stretcher models, their brief treatment of the Satterlee sums up the thoughts of the Medical Department in general on the “regulation hand-litter.”

In order to transport the Satterlee, it had to be deconstructed into its various parts, stacked, and then reassembled when needed. This led to the yokes being “frequently lost” as stated above. At least one matching pair of yokes survives to this day. The pair was inscribed for the 102nd Illinois Volunteers and sold by Cowan’s Auctions in 2016.

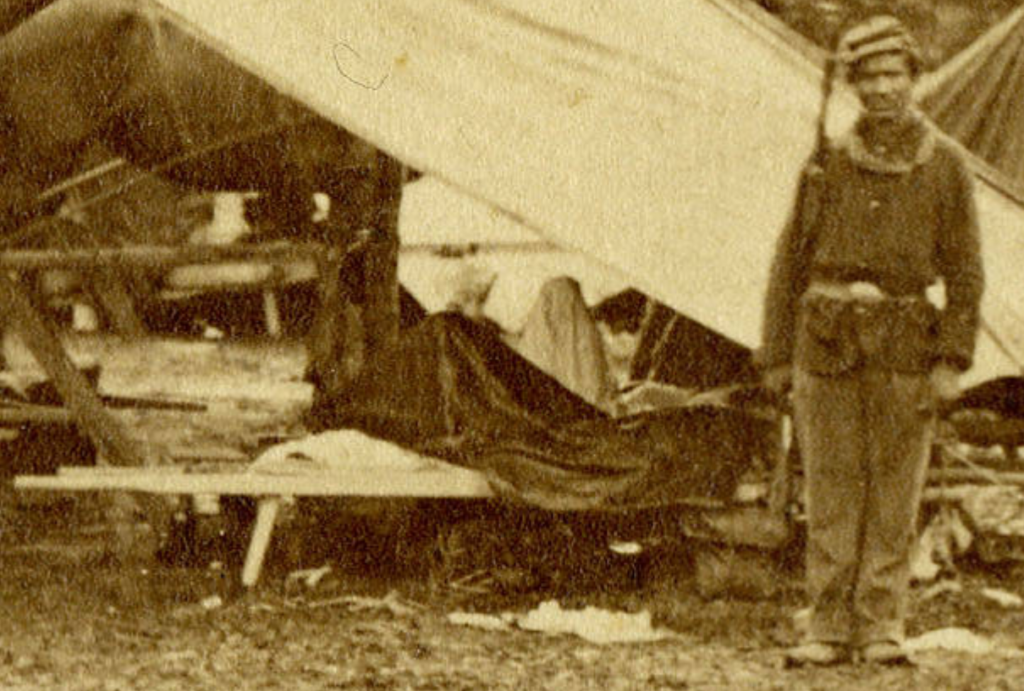

Without the yokes to serve as support in keeping the poles at a fixed distance, the Satterlee stretchers were far less useful. The below photographic detail may show just such a stretcher lacking yokes.

Aside from the difficulty of transportation, it was also a hefty stretcher. Edward Samuel Farrow recorded the dimensions in his Military Encyclopedia, Volume 3, page 72, published in 1895, which you can read via Google Books.

The weight and size of stretchers were a constant issue for stretcher bearers in the period. This was compounded by the age of the musicians that were sometimes serving in that role. In 1864, Dr. Richard Swanton Vickery of the 2nd Michigan Infantry wrote “The less he calculates on them [military musicians] the better. With a few exceptions they are generally worthless as stretcher bearers, many of them being young lads physically incapable of such fatiguing duty.” The inability of the Satterlee to fold in any way also made it difficult to transport. It was the size that the authors of the Medical and Surgical History identified as the main drawback for this model.

As confidently as the authors assert that the Halstead “superseded the Satterlee” both models continued to be used well after the war. As late as 1891, the Surgeon General complained to Congress about the continued use of the “obsolete” Satterlee in training the army’s stretcher bearers.

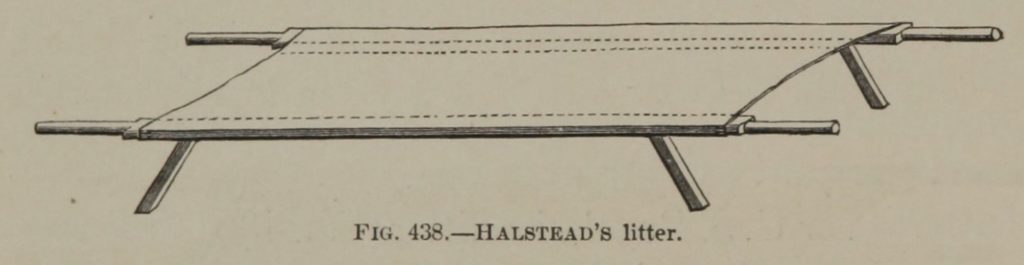

The Halstead

By far the most successful stretcher model in use during the Civil War was the Halstead. Unfortunately, I have been unable to identify the namesake and presumed inventor of the greatest of all Civil War litter models. The authors of the Medical and Surgical History illustrate the success of this model by sheer numbers: “out of the litters (16,807) issued by the New York Purveying Depot twelve thousand eight hundred and sixty-seven (12,867) were of this pattern.” Almost all photographs depicting stretchers in sure during the war are of the Halstead variety.

Hugely successful, the Halstead was widely praised and remained the primary litter for the U.S. Army for decades after the end of the Civil War. Alfred Henry Buck, writing in his 1884 A Reference Handbook of the Medical Sciences, declared that “it is evident that this litter combines to a marked degree all the qualities essential in a hand-litter for field service.” Surgeon John Van R. Hoff was more measured in his praise in 1884, writing that “most of us appear to have been reasonably content with the Halstead.”

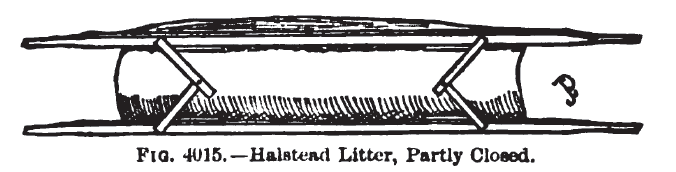

Unlike the Satterlee, the Halstead relied on hinged and permanently affixed cross pieces rather than an easily lost or broken yoke. The hinges were composed of metal bars beneath the bed of the stretcher, allowing it to be folded shut for easier transportation but strong enough to comfortably transport the wounded.

While the metal hinges did provide some advantages over the Satterlee, it posed a danger to unwary bearers. Writing in 1887, Captain Valery Harvard, M.D. warned that hands were often “caught and mangled between the two joints.”

Another distinctive feature of the Halstead was the folding legs. The legs allowed stretchers to act as beds and could be easily set down and comfortably support the patient. These also had some drawbacks, as they do not appear to have stayed folded up while being carried, which may have contributed to snagging or breaking.

While the authors of The Medical and Surgical History wrote that bolts were used to hold the legs and braces in place, the demands of mass production may have changed this. Certainly, subsequent versions were plagued by poor production value. Writing in 1895, Edward Samuel Farrow complained that wooden screws were used to affix both the hinged braces and legs, both of which could be loosened with use and fall out, “rendering the apparatus useless.”

Despite these drawbacks, the Halstead was widely produced and used by the Union army and the most successful of all models developed over the course of the war.

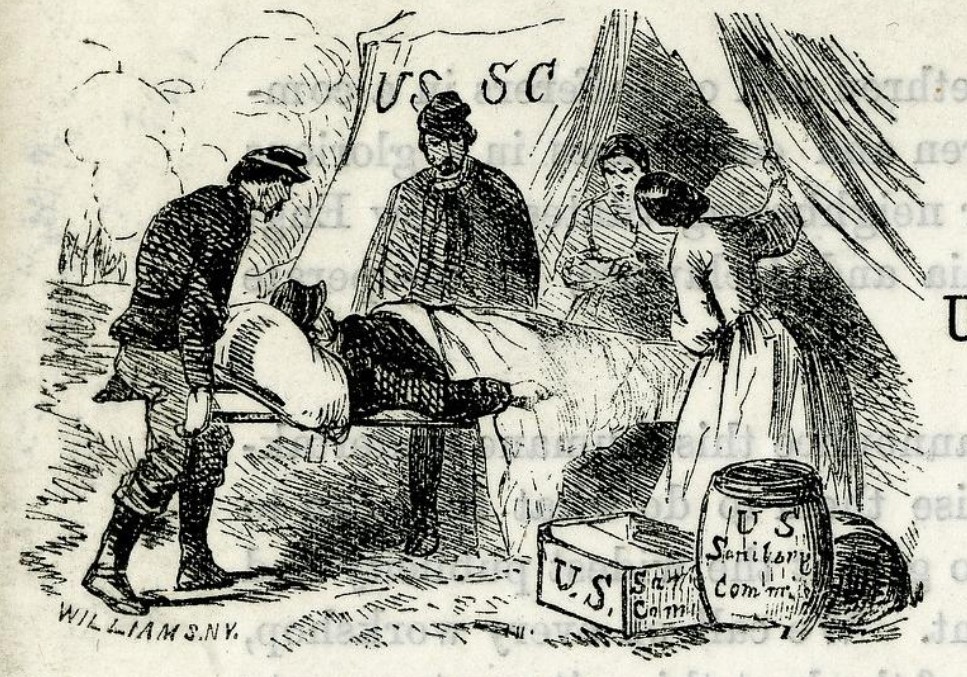

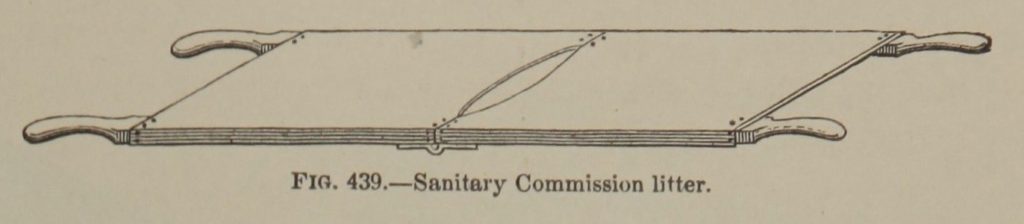

The U.S. Sanitary Commission

The U.S. Sanitary Commission (USSC) is, of course, famous for providing medical and leisure material for soldiers at the front. When it came to stretchers, they developed their own model that was intended to address some of the problems inherent with the standard issue Satterlee and Halstead models. With fixed poles, both the Satterlee and Halstead took up considerable space and were liable to breaking. Both were also hefty, averaging between 23 and 26 pounds. The average soldier weighed around 143 pounds. This means that the stretcher bearers would carry an average of about 96 pounds each.

To address these issues, the USSC adopted a stretcher model that hinged at the center to fold up for easier transport and weighed less (though I have yet to find solid numbers on its exact weight).

The inventor of this model is unclear. It may be that this stretcher model is referred to in the September 21, 1861 letter by the Provost Sanitary Commission General James E. Yeatman encouraging the Western Department to adopt “Twelve of ‘Irwin’s Union Camp Cots’…to every regiment.” Yeatman underlines the word “stretchers” in emphasizing their use and applauds the relatively light weight of twenty pounds.[2] Unfortunately, I have found no other reference to “Irwin’s Camp Cots” and there is too little in the letter to definitively state whether the mysterious Irwin was the inventor of the Sanitary Commission stretcher, or if it was another model entirely.

Writing in 1869, the British Surgeon General Thomas Longmore in his work A Treatise on the Transport of Sick and Wounded (page 140) confused the USSC stretcher with the Halstead, announcing that they were produced in huge quantities. In fact, they were probably rare. Both Longmore and the authors of The Medical and Surgical History agreed that the USSC stretcher was “too fragile for the hard usage of actual warfare.” Longmore may only have devoted space to this model in his book because he wrongly believed it was more widely used than it was. Aside from the above illustration, the authors of The Medical and Surgical History give this model only one sentence in their monumental 3,000-page collection.

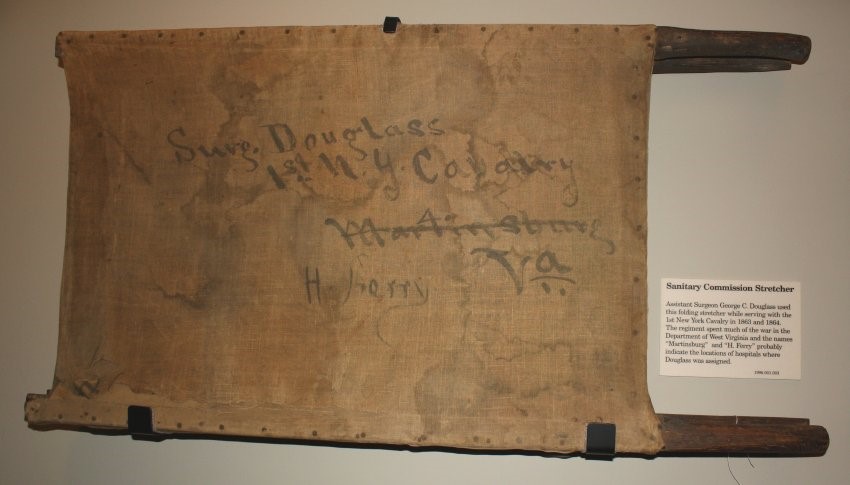

The fragility of the USSC seems to have doomed it both in how many were produced and how many survived. I know of only one original example that still exists. It just happens to be on display at our Frederick, Maryland location!

Assistant Surgeon George C. Douglass of the 1st New York Cavalry owned this piece which is folded in this image. You can see that he put the names of his cities on the stretcher itself. This seems to confirm the assertion by Longmore who granted that while these types were useless in the field they were useful “in the second class; indeed, stretchers intended for use in hospital wagons, and those for other purposes connected with permanent hospitals, are almost universally of the framed kind.” Douglass probably used this stretcher in a permanent or semi-permanent hospital setting, rather than for the evacuation of combat wounded.

The Coolidge

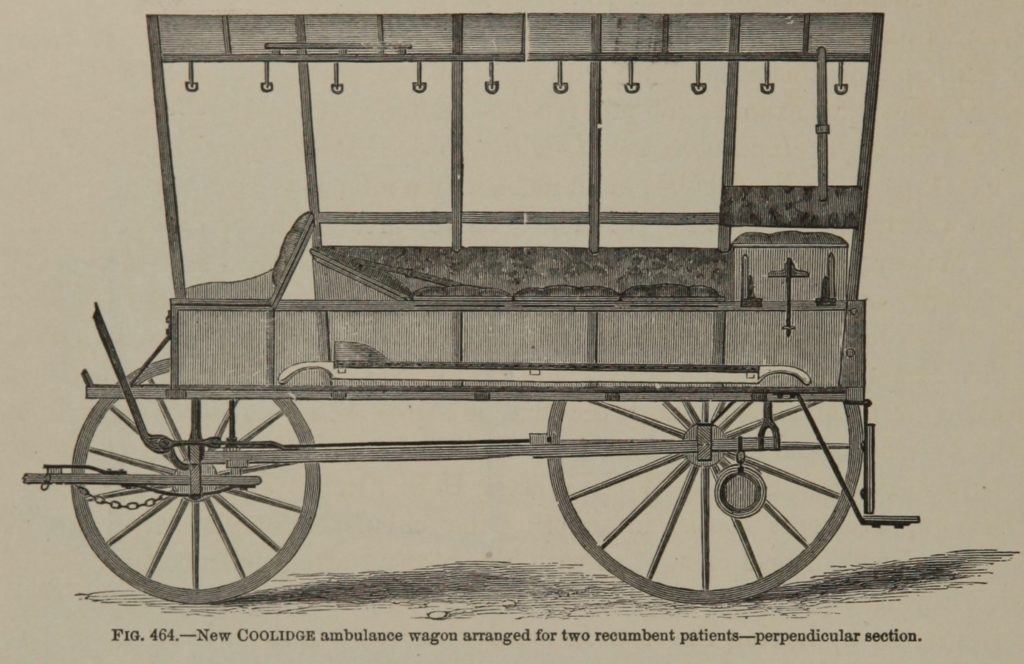

Named for United States Army Medical Inspector Dr. R.H. Coolidge, this stretcher-bed can be used to both carry patients and for longer term care as a bed. The Coolidge Stretcher-Bed was like many litter models in that it was intended to be used in conjunction with a specific ambulance model, also called the Coolidge. The first Coolidge Ambulance was of the two wheeled type so popular in the far West, but dangerously uncomfortable for the wounded of the Civil War. This was superseded by the four-wheeled New Coolidge Ambulance which “was very little used,” but from which this stretcher came.

The folding slat design of the Coolidge Stretcher-Bed allowed for flexibility when it came to care and comfort of wounded soldiers. The slats could be folded into multiple angles to support wounded limbs or fold into seats for the ambulance to carry less grievously wounded men. It was equipped with a mattress as well, probably making it more comfortable than the canvas alternatives that dominated stretcher design in the period.

Once patients arrived at the field hospital, an early form of triage was used to designate who was treated first. For those with less dangerous wounds, a long wait outside the hospital was often what they could expect. These stretcher-beds were ingenious in that patients could be carried long distances in them, but they could also be used for longer term waiting outside field hospitals.

The stretcher-bed gave caregivers the choice to lay the patient flat or prop up the torso and knees by using a system of wooden slats. Another notable feature was the hinged wooden legs that could be used as handles by the stretcher-bearers or fixed in place to convert the stretcher into a hospital bed.

This Coolidge Stretcher-Bed belonged to the 4th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry and is on display at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. This unit saw heavy combat with the Army of the Potomac during the Civil War. While we do not know what engagements this stretcher-bed was used in, we can tell you that stretchers like these became crucial for handling mass casualties after major battles like Antietam, Gettysburg, and the Wilderness, all of which the 4th New Jersey saw action in.

The Tompkins

Here at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine we hold the only surviving example of this deluxe stretcher from the final days of the conflict. It is a heavily altered original, but nonetheless a fascinating and rare piece.

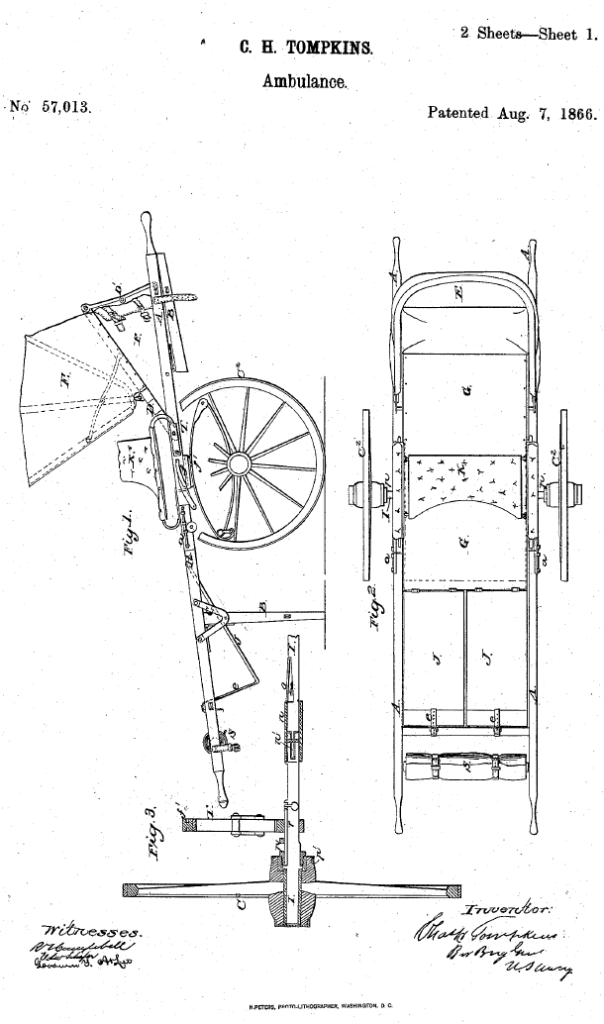

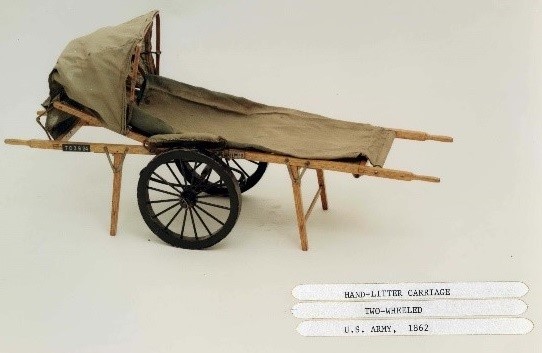

Developed by Brigadier General Charles Henry Tompkins very late in the war, his model boasted bonnet to shade the wounded and detachable wheels with springs to make the ride smoother for the wounded and less onerous on the bearers.

In 1866, Tompkins patented his invention and managed to earn positive reviews from many of his fellow Union army veterans. The image below is from “Improvements in Stretchers,” Charles H. Tompkins, United States Patent Office, August 7, 1866, via Google Patents.

After the war, Tompkins launched a major advertising push to encourage wider adoption of his model. This included piece in The Scientific American and a pamphlet entitled “The Tompkins Stretcher, or, Wheeled Litter,” a copy of which is in the collection of the National Library of Medicine and available digitally through their website.

The Tompkins Stretcher (though not identified as such) also makes an appearance in The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion’s treatment of medical evacuation (Volume II, Part III, page 926).

A scale model of the stretcher is on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine, probably submitted with the patent application in 1866, and possibly misidentified in this photograph as submitted in 1862.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

Endnotes

[1] Later a Brevetted Brigadier General

[2] Recommendation of the Sanitary Commission by the President, James E. Yeatman, September 20, 1861, Missouri History Museum via Wikimedia Commons.

About the Author

Kyle Dalton is a summa cum laude graduate of the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, where his paper Active and Efficient: Veterans and the Success of the United States Ambulance Corps was awarded the Zeender Prize for best history thesis. In his spare time Kyle writes and maintains a website on the lives of common sailors in the eighteenth-century: BritishTars.com.