Table of Contents

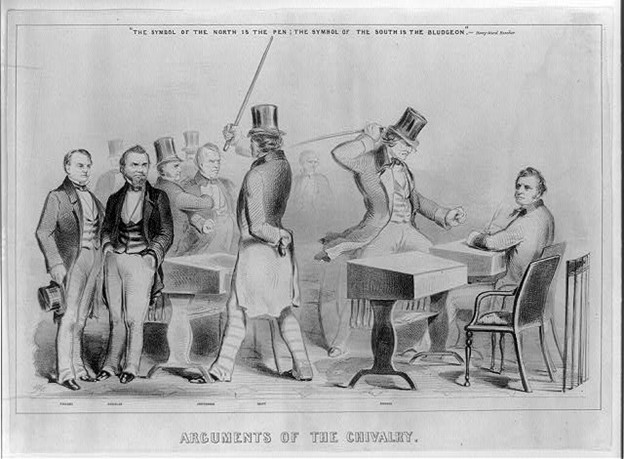

Political rivalries and division have been part of our nation’s government since the founding with the ideological split between Thomas Jefferson (anti-federalist) and John Adams (federalist). However, at no point in our nation’s history have we been more divided and polarized than during the decade leading up to the Civil War. The new Republican party (1856) founded itself on being an anti-slavery party dedicated to preventing the westward expansion of slavery. Men from around the country flocked to the voting booths in hopes of sending to the White House an anti-slavery Republican or a Democrat, who wished to leave the slavery question to the individual states. This caused an ideological divide between two parts of the country and laid the groundwork for the Civil War. The intense divisions eventually erupted violently in the halls of Congress.

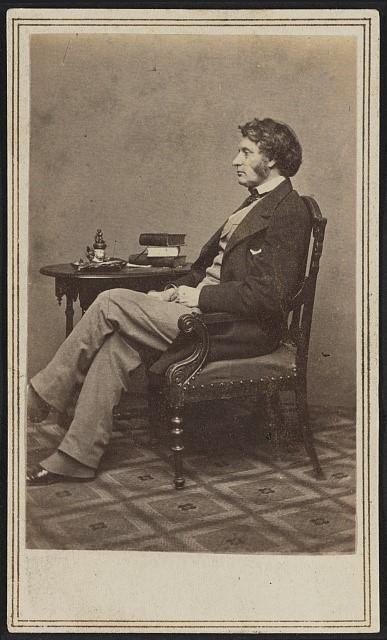

One Northern politician who was adamantly against the institution of slavery was Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner. Sumner’s towering frame was only outmatched by his commanding presence at the podium and his outspoken political views on the institution of slavery. He was elected to serve in the senate in 1851 after a career as a lawyer and orator where he argued a case before the Massachusetts Supreme Court on the legality of segregated schools – Roberts v. Boston (1850).

In the halls of Congress, Sumner, along with many of his Northern colleagues, were very outspoken against the Fugitive Slave Act and later, the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854). In the case of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, it allowed territories to decide for themselves if they were to become a free or slave state. Sumner believed that outside agents would act on behalf of the slaveholders to persuade the state of Kansas into becoming a slave state. Sumner’s prediction came true during Bleeding Kansas, where outside actors from both parties flocked to Kansas to influence the vote. This erupted in a string of beatings, shootings, and a few massacres committed by both sides.

This event prompted Sumner to give a speech in the halls of Congress from May 19-20, 1856. In the two – day speech, titled “The Crime Against Kansas,” he called out southern interference by saying “the rape of a virgin Territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of Slavery; and it may be clearly traced to a depraved desire for a new Slave State… in the hope of adding to the power of Slavery in the National Government.”[1]

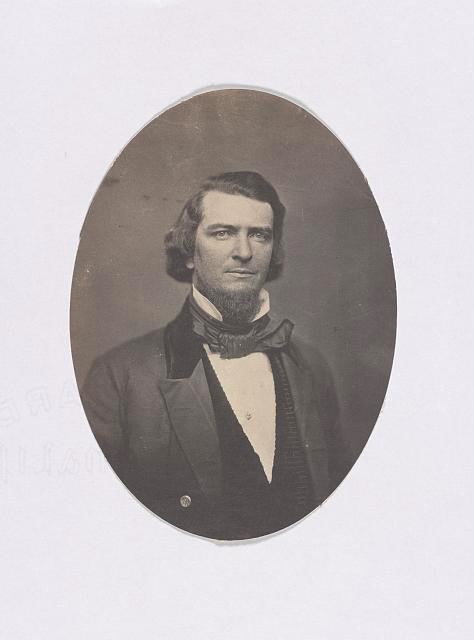

Sumner also condemned Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas and South Carolina Senator Andrew P. Butler, the authors of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. In his speech, Sumner said about Butler that “he has chosen a mistress… who, though ugly to others is always lovely to him, though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight; I mean the harlot Slavery.”[2] At the time of his speech, Senator Butler was not present. His colleague and relative however, South Carolina Representative Preston S. Brooks, was present. Appalled by the words of Senator Sumner, Brooks believed him not to be a man of honor, otherwise he would have challenged him to a duel as many of the Southern aristocracy still did when their honor was questioned.

Instead of an honorable duel, on May 22, 1856, Brooks took the cane he began using after receiving an injury in a duel, and proceeded to beat Senator Sumner ferociously, “Moving quickly, Brooks slammed his metal-topped cane onto the unsuspecting Sumner’s head. As Brooks struck repeatedly, Sumner rose and lurched blindly about the chamber, futilely attempting to protect himself.”[3] On one of Brooks’ swings with his gutta-percha, metal topped cane, the cane top broke off on impact. Finally, after a full minute of Brooks beating Sumner, the two were separated and Sumner was carried away to be treated for his wounds.

With the Senate chambers mostly full, there were many witness accounts of the attack. These eyewitness accounts were used in a Senate inquiry into the event, recorded in the Washington Sentinel and published several months later. The account of Senator Foster of Connecticut recalled that he, “heard a sudden unusual noise, and turning round, saw Brooks striking Sumner in his seat rapidly over the head. Sumner attempted to rise, and looked as though reeling, and partially unconscious.”[4] Senator Robert Toombs of Georgia and future Confederate general recalled, “Brooks was striking right and left. Sumner spun round, and getting into the main aisle fell. When he fell [witnesses] saw blood over his forehead; blood was also running down his clothes.”[5]

Dr. Cornelius Boyle, a well-known Washington physician, was the first to attend to and examine Sumner after the beating. Sumner had several gashes on his head along with extensive bruising to his hands, neck, and shoulders. Dr. Boyle testified that “the scalp had been cut through to the bone in two ragged cuts, one, two and one quarter inches long and very ragged, a second, somewhat less than two inches; and that there was no concussion of the brain but much loss of blood.”[6] Several days later, Dr. Boyle was dismissed after failing to recognize the signs of an oncoming fever, he was replaced by Boston physician Dr. Marshall Perry.

Dr. Perry treated Sumner’s condition with opiates and restricting visitor access. Drs. Harvey Lindsly and M. Miller were called in to assist before Perry returned to Boston shortly after Sumner’s condition improved. By late June, Sumner returned to the Senate floor for a brief moment before becoming overwhelmed by the Mid-Atlantic summer and his condition deteriorated. He was able to recover in Philadelphia and returned to Boston several months later to secure his reelection. For the next year and a half, Sumner continued his recovery before going to Europe two years after the initial attack.

After the beating, Sumner suffered from head trauma and what would be diagnosed today as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Sumner spent some time recovering in Europe and wound up in Paris a year after the attack. According to historian David McCullough, “the beating left him very damaged both psychologically and physically and he went back to Paris several times to relieve himself of these anxieties that he felt and his inability to perform as a Senator.”[7]

His physician in Paris was the famed Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard. Séquard believed that he would be able to treat Sumner’s spinal cord injury by burning the skin along the spinal cord. Sumner agreed to the procedure and chose to go forward without anesthesia as it was believed to reduce the procedure’s effectiveness – though the burning of the skin certainly did little good either way. Sumner began to recover from both the treatment and from the wounds for another year until his official return to the Senate in 1859. His recovery lasted for about three years, and he would not make another speech until the following year in 1860 called “The Barbarism of Slavery.”

Almost immediately after Sumner’s beating, both Sumner and Brooks were seen as heroes to the cause by their respective regions and vilified by the other. The caning of Sumner galvanized support among abolitionists, antislavery, and republicans across the country while also bolstering the resolve of the slaveholding Democrats of the South and their Northern supporters. However, with the Union victory in the Civil War, Charles Sumner and his allies would see their vision through with the passage of the 13th Amendment, formally abolishing the institution of slavery.

Sumner was also a vocal supporter of one of the nation’s most important amendments to the Constitution, the 14th Amendment, which guaranteed citizenship to all those born in the United States and offered a pathway for immigrants to become citizens as well. In later years, the 14th Amendment would be used in some of the most important Civil Rights cases in America such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Loving v. Virginia (1967), and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). Needless to say, Charles Sumner was one of the most outspoken and influential politicians and many of our civil rights and liberties, we owe to the work done by Sumner and his colleagues.

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021. He is currently pursuing a Masters in American History from Gettysburg College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute.

Sources

[1] Alexander, Edward. “The Caning of Charles Sumner.” American Battlefield Trust, June 4, 2021. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/caning-charles-sumner.

[2] Alexander, Edward. “The Caning of Charles Sumner.” American Battlefield Trust, June 4, 2021. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/caning-charles-sumner.

[3] “The Caning of Senator Charles Sumner.” U.S. Senate: The Caning of Senator Charles Sumner, May 4, 2020. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/The_Caning_of_Senator_Charles_Sumner.htm.

[4] “Office of U.S. District Attorney.” Washington Sentinel. July 10, 1856.

[5] “Office of U.S. District Attorney.” Washington Sentinel. July 10, 1856.

[6] White, Laura A. “Was Charles Sumner Shamming, 1856-1859?” The New England Quarterly 33, no. 3 (1960). Pg 293

[7] Lamb, Brian. Q&A With David McCullough. Other. C-SPAN, May 11, 2011. https://www.c-span.org/video/?299417-1/qa-david-mccullough-part-one.