Table of Contents

The Civil War is one of the most heavily documented conflicts in American history, and it’s no surprise that there are some strange and unusual tales to be found among newspapers, military accounts, and medical records.

Union and Confederate surgeons conducted tens of thousands of operations on wounded soldiers, but sometimes, an operation was not necessary to remove a foreign object. In two cases, it seems the soldiers themselves were more successful on their own. Capt. Roland E. Hackett, of Co. A, 26th Kentucky Infantry, was wounded at Nashville, on December 15, 1864. He was on horseback, cheering his men, and had his mouth wide open. A pistol bullet struck him in the mouth, injuring his tongue and knocking out three of his teeth. When brought into the hospital, a surgeon removed one of the teeth that had lodged at the base of his tongue. He was not suffering much pain, but his voice had a very muffled peculiar sound, as if something was lodged in his throat. Thirty-six hours after being wounded, the bullet was found in his bowel movement. It apparently had passed into his esophagus and down into his stomach. After 20 days of recuperation, he was returned to his regiment.[1]

Similarly, Pvt. James T. Dowdy, of the 28th Virginia Infantry, was wounded by a minie ball at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863. The ball entered the lower part of the breastbone. Fourteen hours after being wounded, he had a large bowel movement, and heard something fall heavily and loudly to the bottom of the bedpan. The nurse found a large minie ball. He was eventually paroled and in 1870 was found to be living and in good health.[2]

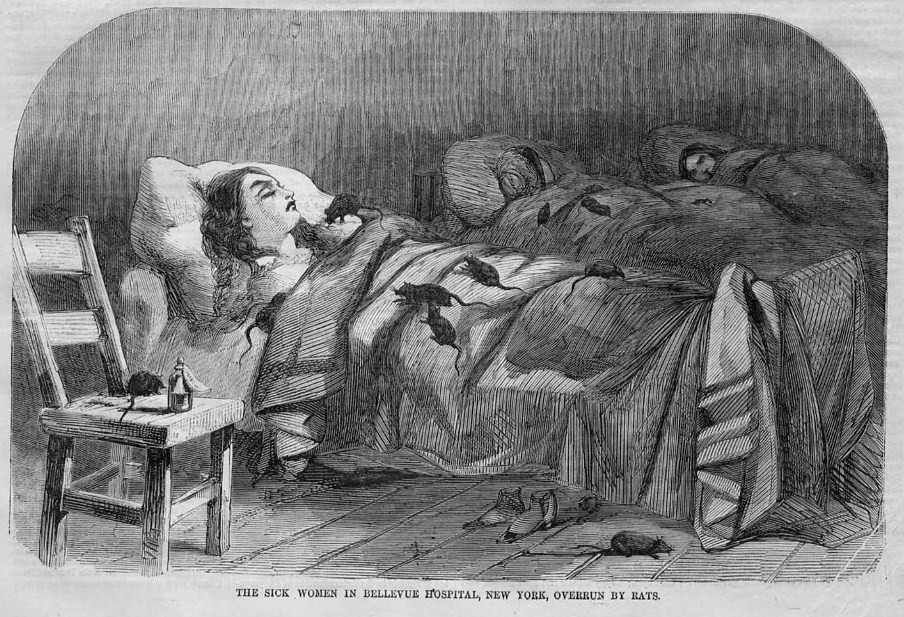

In one particularly unusual incident, it seems that nature provided its own surgeon. As reported in the Daily Intelligencer of September 26, 1863, under the headline “Surgeon Rat” and credited to the Petersburg Express:

We have heard and read a great many stories about the rat, but in all our experience, we have never before had one brought before us in the character of a surgeon. We learn that in one of our large hospitals a night or two since, an operation was successfully performed upon an invalid soldier by a common rat, which the surgeon in charge had himself delayed for a time, with the hope of causing less suffering to the patient. The patient was suffering from the effect of a fracture of the frontal bones of the skull – a piece of which projected outwards to some length, and the healing of the fleshy parts depended on its removal. The bone was so firmly fixed, however, as, in the opinion of the surgeon, would cause unnecessary pain in its forcible removal, and such remedies were applied as would assist nature in eventually ejecting it. A soothing poultice was placed on apart a night or two ago, a hole being made through the application for the insertion of the projecting bone,-The patient was soon asleep in his bed; but during the night was aroused by a sting of pain, and awoke to discover the rat making off with the piece of bone in his mouth. He struck at and hit the rat, but did not hurt him.

The rat had probably been drawn to the bed of the soldier by the scent of the poultice, which was pleasant to his olfactories: but upon reaching it, his keen appetite, no doubt, caused him to relish in a large degree the juicy bone so convenient to his teeth. He therefore seized and drew it from its position, and was made to scamper off by the patient whom he had aroused with pain. It was a skillful operation, quickly performed, and will result beneficially to the invalid. We understand the patient is getting on remarkably well.

The story of Civil War medicine has many fascinating aspects, including the development of the ambulance corps and the implementation of triage. If you look closer, however, you may find some surprising stories like these.

About the Author

Tracey McIntire earned her BA in English at Rivier College in Nashua, NH. She is Director of Communications at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, and an interpretive volunteer at Antietam National Battlefield. She is also an active Civil War living historian, where she portrays a woman soldier in various guises.

Sources

[1] Medical and Surgical History of the Civil War, Volume 10, page 99

[2] Ibid.