Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

“Many, we know, cannot offer joyful thanks today,” Reverend Robert H. Williams told his congregation on November 24, 1864. Newly re-elected President Abraham Lincoln had set aside the fourth Thursday of the month as a day of thanksgiving. The residents of Frederick, Maryland gathered in the town’s churches that day – many of whom were in the seats at the Presbyterian Church to hear Reverend Williams.

“If we enter home today in any part of our land,” he told his parishioners, “we will hear a bitter tale of woe. The wife will tell of her husband, who fell in the bloody strife. Some will tell of friends, who suffered many months from fearful wounds.”

On the southern end of the city, Surgeon Robert F. Weir planned a Thanksgiving celebration that Thursday to benefit those recovering from those “fearful wounds” in the wards of U.S. General Hospital #1. As the head surgeon in the city’s sizeable hospital, it fell to Dr. Weir to suitably mark the occasion.

“A sumptuous dinner will given by Dr. Weir,” the hospital’s chaplain told the editors of the Frederick Examiner on November 23, 1864. “Let our citizens, who are cordially invited to attend, go prepared to contribute something to the comfort and enjoyment of the soldiers.” The chaplain called on citizens to give donations in money and books to help replenish the hospital’s meager library.

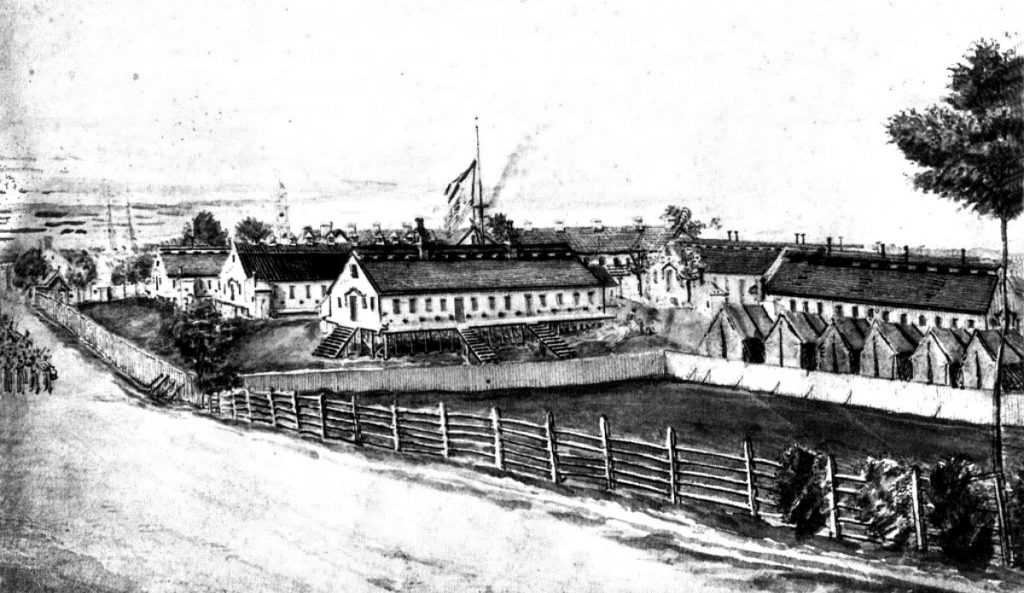

The hospital had been serving the wounded, sick, and dying since the autumn of 1861. It had grown to include an entire campus, with hospital wards radiating outward in a “pavilion-style.” An observer in November 1864 described the conditions in the hospital that month:

I was peculiarly impressed with the capacity and conveniences of this well ordered receptacle of disabled patriots. It is situated in the southern precincts of the city… The grounds are ample, checkered with plain and gravel walks and enclosed with a neat and substantial fence. The buildings are commodious… The balance are wooden, nicely painted and perfectly clean within and without, presenting altogether a picture of architectural uniformity and neatness. There are accommodations for perhaps 1,200 patients.

Every consistent and attainable accommodation, every appliance for the mental or physical comfort of sick and wounded men may be found there.

Surgeon Weir and the hospital’s chaplain planned a full day of observances for the hospital and its patients. Their schedule included a service in the hospital’s chapel at 11 AM with a “thank offering… to be applied to the enlargement of the soldier’s Library” and a Thanksgiving dinner at 3 PM.

The hospital’s grounds would be open to the public, no passes necessary, throughout the day. Following services in Frederick’s many churches, residents headed toward the hospital to mark the occasion with the convalescents.

“At the hospital, the day was appropriately observed,” reported the Frederick Examiner, “[with] quite a number of citizens lending their presence in order to assist in the celebration of the occasion.”

The dinner was “heartily enjoyed by the inmates of the Hospital,” and the collection taken during the course of the day netted more than $50 to assist in the purchasing of new books for the facility’s library.

As the Civil War’s bloodiest year came to its close, citizens and soldiers alike realized they had a lot to be thankful for despite the dreary situation. Union armies were victorious throughout the theater of war, slavery in Maryland had been peacefully extinguished, and the terrible hand of war appeared to have retreated from Frederick forever.

As Reverend Williams at the Presbyterian Church concluded his message on Thanksgiving Day 1864, he alluded to the hopes and fears of future events. He eloquently summarized the thoughts and feelings surely felt by those in his divided community:

During the past four years great changes have taken place. The changes of the next four years, no doubt, will be as great as those through which we have just passed. Who can tell what shall be the result of the next year?

Probably, even in hostile territory, tears of real, earnest sorrow may be shed over the graves, and uncoffined and buried bones, of our patriot soldiers. Probably, the scars received in battle may command the respect of all, and be one qualification for honorable positions.

Happy day when the peans of victory and the sweet notes of peace shall blend beautifully together – when a mighty people shall lay aside their discord, and man meet man as brothers of a noble race, and sons of a free, united, and prosperous nation.

That “happy day” would come after five more bloody months of unrelenting combat.

About the Author

Jake Wynn is the Program Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He also writes independently at the Wynning History blog.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.