Table of Contents

One of the greatest fears of a Civil War soldier was to be killed on the battlefield or to die in a field hospital as an unknown. It is said that just before the battle at Cold Harbor in 1864, many Union soldiers, knowing that a frontal assault would be deadly, wrote their names on pieces of paper and pinned them inside their jackets so that their bodies could be identified.

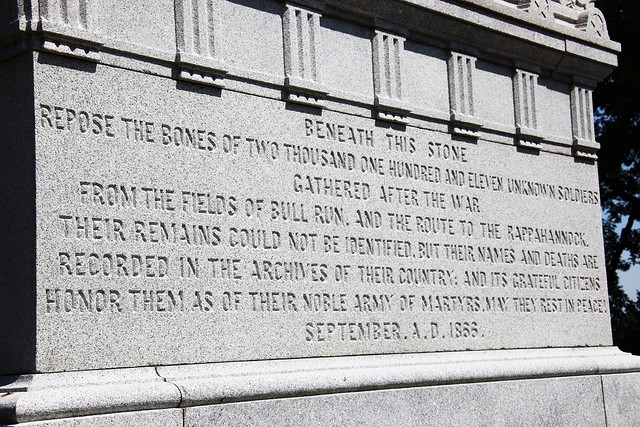

Given the mass casualties that occurred during the Civil War, it is not surprising that the numbers of unidentified soldiers were quite large. Of the more than 325,000 Union soldiers buried in National Cemeteries, almost 149,000 are unknown.[1] The number of unknown Confederates is thought to be even larger. It is estimated that 5% of the combined Union and Confederate dead remain unidentified.[2] It was no wonder that soldiers feared “the nameless grave.”

At the start of the Civil War, neither army issued any form of identification to recruits. Identification discs, later to be called “dog tags” were not issued by the federal government until 1906.[3] In May of 1862, John Kennedy, a resident of New York, had sent a letter to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, suggesting that each Union soldier be issued an ID tag and offering to manufacture them. Unfortunately, this suggestion was rejected without an explanation. While burial practices for battlefield dead had been standardized since 1861, and quartermasters were charged with keeping proper mortuary records and providing registered headboards for each soldier’s grave, not much could be done if there was no identification on the body to begin with.[4]

The soldiers and their families took matters into their own hands. When leaving home, a soldier would often be given a coin or a bit of lead or copper to carry with them that had been engraved with their name. Due to the awareness of civilian industries for the growing need for this type of identification, jewelers and others began to manufacture discs that could be engraved or stamped.

Two types were available: discs that were meant to be hung around the neck or pins to be worn on the chest. Made of lead, copper, or brass, the soldier’s information would be stamped on the disc or pin using die-cut letters. Officers and others with monetary means might order badges made of gold or silver that were engraved with their information. A soldier could either purchase the item from a sutler (a seller of various wares who set up shop in army camps) or by mail-order. Manufacturers would take out advertisements in the popular newspapers of the day, such as Harper’s Weekly: “Attention Soldiers! Every soldier should have a badge with his name marked distinctly on it . . . a solid silver badge that can be fastened to any garment.”[5]

Many of these discs would have patriotic themes and feature an eagle, a favorite general, or an inscription such as “War of 1861.” The reverse side would be blank to allow for engraving or stamping the soldier’s name, company, regiment, and hometown. Sometimes both sides were blank, allowing a space for the soldier to list the battles in which they had participated.[6] In order to save on expenses, jewelers and sutlers would sometimes use a U.S. quarter dollar silver coin. One side was shaved smooth to accommodate the engraving and a pin soldered onto the back for the soldier to attach it to their uniform.[7]

Because of the lack of industry and materials, Confederate soldiers did not go to the extent that the Union soldiers did to provide their own identification. In fact, there is little mention of them using any type at all. Some rare existing examples are made of thin-sheet silver or brass, with designs such as stars or crescents. Some were just plain metal sheets with the soldier’s name embossed.[8]

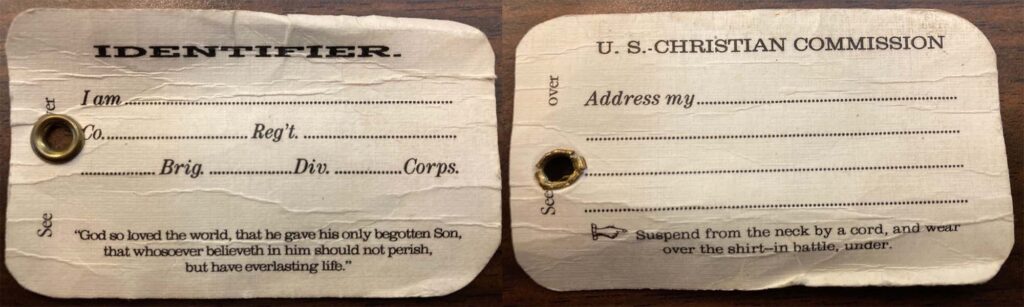

The U.S Christian Commission and the U.S. Sanitary Commission were civilian organizations staffed by volunteers whose mission was to provide necessary items to Union soldiers that the government could not. Similar to the Red Cross today, they brought “care packages” for soldiers that would contain items such as new socks, mittens, newspapers, tobacco, and candy. To address the soldiers’ concerns of identification, these organizations also provided paper identification tags that could be filled out with the soldier’s name and other information. The tags were to be “Suspend[ed] from the neck by a cord, and [worn] over the shirt—in battle, under [the shirt].”

The US Christian Commission also distributed Bibles to the troops. Some soldiers who had Bibles of their own had taken to writing their name and address in the flyleaf, in hopes that it would aid in identifying their body. The USCC made this easier by affixing labels in the front of the Bibles they distributed that the soldiers could quickly fill out with the pertinent information. The label also allowed for writing in the information of the next of kin with the plea that “Should I die on the battle field or in Hospital, for the sake of humanity, acquaint [next of kin] residing at [address] of the fact, and where my remains may be found.”

After the Civil War, famous humanitarian Clara Barton set up the “Missing Soldiers Office” in her boarding house in Washington, D.C. She received thousands of letters from families requesting information on their missing loved ones. Thanks to her perseverance, Barton was able to determine the fate of over 22,000 of those soldiers. But even her heroic efforts were unable to identify all of the unknowns. Perhaps if the governments of the armies had issued some form of ID to all of their recruits, her job might have been easier, and there would be fewer graves with their contents “known but to God.”

About the Author

Tracey McIntire earned her BA in English at Rivier College in Nashua, NH. She is Director of Communications at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, and an interpretive volunteer at Antietam National Battlefield. She is also an active Civil War living historian, where she portrays a woman soldier in various guises.

Sources

[1] McCorkmick, David. “Civil War Soldiers Made ID Tags,” Antiqueweek.com, 6/25/2010

[2] Swain, Steve. “Civil War Dog Tags: Sutlers Solve the ID Dilemma,” The Ephemera Society of America

[3] Riddle, Lincoln. “The History of Dog Tags,” War History Online, 1/16/2017

[4] Groeling, Meg. The Aftermath of Battle: The Burial of Civil War Dead, 2015, page 7

[5] Swain, Steve. “Civil War Dog Tags: Sutlers Solve the ID Dilemma,” The Ephemera Society of America

[6] Troiani, Don. “Civil War Identification Badges,” Warfare History Network

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.