Table of Contents

Today we approach marijuana and cannabis as legal or illicit. Their use is regulated as medical or recreational. Like all drugs, cannabis and marijuana were virtually unregulated and freely available in the mid-19th century and the available cannabinoids could be far more potent than what is available today.

Sidney George Fisher, a resident of Philadelphia, recorded this in his diary on November 3, 1863:

“[Dr.] Wister here in the evening. The medicine he gave me caused me an agreeable mental excitement, which I mentioned to Bet [Fisher’s wife]. The reason was that Indian hemp, or Hasheesh, was one of its ingredients. I have read of its wonderful powers over the mind & spirits, but never tried it before. It is certainly a very pleasant way of curing gout.”[1]

Fisher’s use of the words “Indian hemp” distinguishes it from the locally grown hemp that was largely used for producing rope. Henry Beasley, in his 1865 The Book of Prescriptions, makes the difference clear: “Indian Hemp [Cannabis Indica] is generally considered to be the same species as Cannabis sativa of Europe; but in the East it secretes a resin, and acquires peculiar properties which it does not possess in Europe.”[2] To this day the medical community debates over the difference between indica and sativa, or if there even is one, but for our purposes the most important difference is that hemp grown in America was not intended for consumption but production. As such, farmers were not growing hemp with high CBD or THC levels in America, and medicinal cannabis was being imported from overseas.

Tilden’s Extract of Cannabis indica was the preferred recreational drug of choice for Fitz Hugh Ludlow: “For the humble sum of six cents I might purchase an excursion ticket over all the earth; ships and dromedaries, tents and hospices were all contained in a box of Tilden’s extract.” Ludlow further confessed in his autobiographical 1857 work The Hasheesh Eater that when taking Tilden’s Extract “the whole atmosphere seemed ductile, and spun endlessly out into great spaces surrounding me on every side,” but warned that its use “leads at last into poisonous wildernesses.”[3]

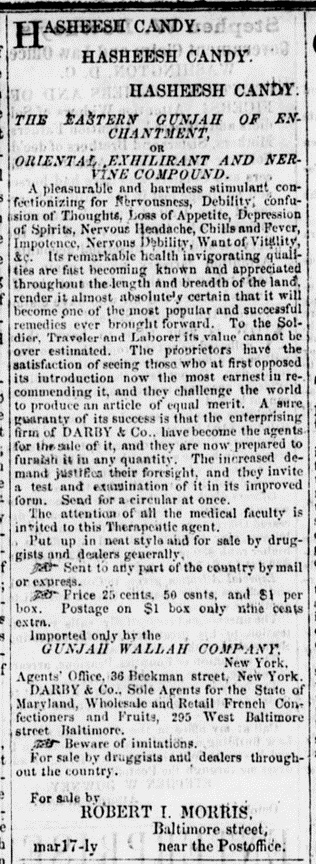

Unlike the marijuana that is smoked by many users today, cannabis was most often available consumed as an extract. In Henry Beasley’s 1865 The Book of Prescriptions, he writes only that “The resinous extract is imported from India” and makes no mention of smoking as an option for treatment.[4] Newspaper advertisements for cannabinoids (like the one below) are numerous throughout the conflict, especially in the North, and often advertise candied extract.

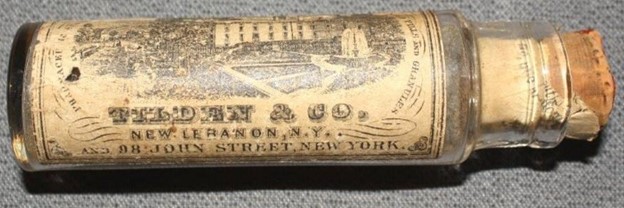

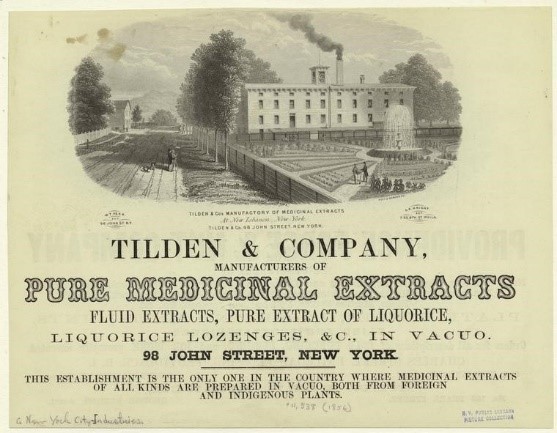

Tilden & Co. produced a huge range of extracts for everything from coffee to hydrangeas. In our collection is a vial of Hyoscyamus extract. Among their most popular was the abovementioned cannabis.

In 1852, a Tilden & Co. catalog recommended that “a desirable form for administering” their cannabis extract “in domestic practice, is to mix an ounce of the Fluid Extract with a pint of simple syrup, to be given in the dose of from twenty-five to fifty drops.”[5]

Consuming extracts had decidedly different effects than smoking and could be incredibly potent. As described by Oriana Josseau Kalant, an addiction specialist writing in the 20th century:

Ludlow consistently talked of ‘hasheesh,’ but in fact he took the solid extract of Cannabis indica which was roughly twice as potent as the crude resin and ten times as potent as marijuana. A rough calculation shows that his intake was equivalent to about 6 or 7 marijuana cigarettes per dose, i.e., at the hallucinatory rather than at the euphoriant level prevalent in contemporary North American use.”[6]

Considering that Tilden & Co. advertised a single dose as “five to 10 drops” on the same page where they recommend “twenty-five to fifty drops,” the effect could be staggeringly multiplied by a confused user.[7]

It is important to note that, in the words of Dr. Mark Breazzano, these are all rough calculations, and “it is challenging to compare specific potency between each of these compounds without knowing exact concentrations.”[8]

Widely available to the civilian populace, cannabis does not appear to have been prioritized as a treatment by army surgeons of either side. In civilian life it was often advertised for and used in treating nervous and mental conditions, as related in the Memphis Medical Recorder which reported in 1858 on a case in which Tilden’s Extract of Cannabis was prescribed “after several months of uninterrupted insanity, the patient, a man of twenty-two years of age, appears to have wholly recovered.”[9]

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, patent medicines were increasingly regulated at the state and federal level. These medicines were often poisonous, ineffective, or (in the case of Tilden’s Extract) dangerously potent for self-medication without a prescription. These medications built fortunes with repeat customers captured through addiction. Samuel J. Tilden, heir to the extract fortune, gained enough power to win the Democratic candidacy for president in the 1876 election and won the popular vote. Addiction crises among patent medicine users, especially those with opioid ingredients, spurred action to clamp down on the patent medicine industry. The business eventually sputtered out with the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act.

In our much more regulated pharmaceutical industry today, a re-examination of cannabis as a treatment for certain conditions has gained traction among both potential users and pharmacists. As of 2021, there are only five states in the nation in which all forms of cannabinoids are illegal.[10] There is still much research to be done on potential side effects, consumption by young users, and long-term consequences of use.[11] There are also promising studies underway evaluating cannabinoid treatments of PTSD,[12] epilepsy,[13] and Alzheimer’s disease.[14] Importantly, as Dr. Breazzano states, “these studies are looking at specific molecular targets rather than the entire marijuana resin or hash as a treatment.” The research is still very much underway.[15]

Tilden’s Extract of Cannabis was overly powerful for an unregulated market, and a lack of oversight and careful scientific study will always pose a risk to users. “Regardless of the substance including marijuana, regulation (especially knowing exactly what and how much) is important for every administered drug. Even over the counter supplements, for example, do not have regulatory oversight like prescription drugs and therefore carry additional potential risk.”[16]

This tiny vial that once held an alarmingly powerful extract shows that what was old is new again: a once questionable substance peddled irresponsibly that in a new context shows real potential.

About the Author

Kyle Dalton is the Membership and Development Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is also a summa cum laude graduate of the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, where his paper Active and Efficient: Veterans and the Success of the United States Ambulance Corps was awarded the Zeender Prize for best history thesis. In his spare time Kyle writes and maintains a website on the lives of common sailors in the eighteenth-century: BritishTars.com.

Endnotes

[1] A Philadelphia Perspective: The Civil War Diary of Sidney George Fisher, edited by Jonathan B. White. Fordham University Press, 2009. Page 207.

[2] Beasley, Henry, The Book of Prescriptions, Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1864, page 176, via Google Books, accessed August 17, 2021, <https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Book_of_prescriptions/AZSswFNL-uAC?hl=en&gbpv=0>.

[3] Fitz Hugh Ludlow, The Hasheesh Eater: Being Passages from the Life of a Pythagorean, New York: Harper and Brothers, 1857 pages 22, 64, and 276, via Google Books, accessed July 23, 2020. <https://books.google.com/books?id=ZZARAAAAYAAJ>.

[4] Beasley, 176.

[5] “Fluid Extract of Cannabis indica,” in Catalogue of Pure Medicinal Extracts, Prepared in Vacuo at the Steam Works of Tilden & Co, New York: Tilden & Co., 1852, via Google Books, accessed August 17, 2021, <https://www.google.com/books/edition/Catalogue_of_Pure_Medicinal_Extracts_Pre/WnbtAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0>.

[6] Oriana Josseau Kalant, “Ludlow on Cannabis: A Modern Look at a Nineteenth Century Drug Experience,” via the Schaffer Library of Drug Policy, accessed July 23, 2020, <https://druglibrary.net/schaffer/History/kalant.htm>.

[7] “Fluid Extract” in Catalogue.

[8] Dr. Mark Breazzano, e-mail with the author, September 7, 2021.

[9] Quoted in The Eclectic Medical Journal, R.S. Newton M.D. editor, Fifth Series, Vol. II, Cincinnati: R.S. Newton, June 1858, page 266, via Google Books, accessed August 17, 2021, <https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Eclectic_Medical_Journal/CnkBAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0>.

[10] Map of Marijuana Legality by State, DISA Global Solutions, accessed August 19, 2021, <https://disa.com/map-of-marijuana-legality-by-state>.

[11] “Marijuana Drug Facts,” National Institute of Health, National Institute on Drug Use, accessed August 19, 2021, < https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/marijuana>.

[12] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6397040/

[13] https://www.epilepsy.com/learn/treating-seizures-and-epilepsy/other-treatment-approaches/medical-marijuana-and-epilepsy

[14] https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-alzheimers-disease/jad140093

[15] Dr. Breazzano e-mail.

[16] Ibid.