Table of Contents

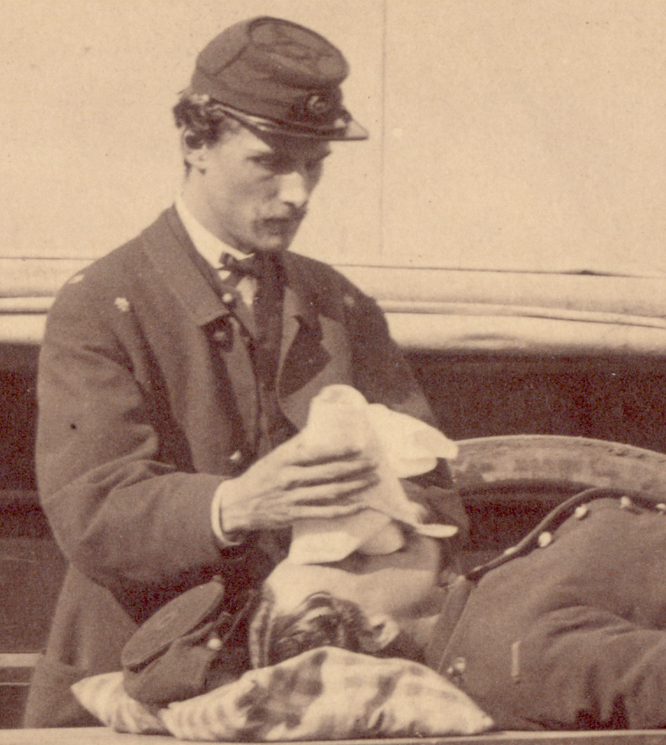

In the generation since the introduction of general anesthesia, it was incredibly rare that any surgeon would dare attempt a major operation without chloroform or ether on hand.

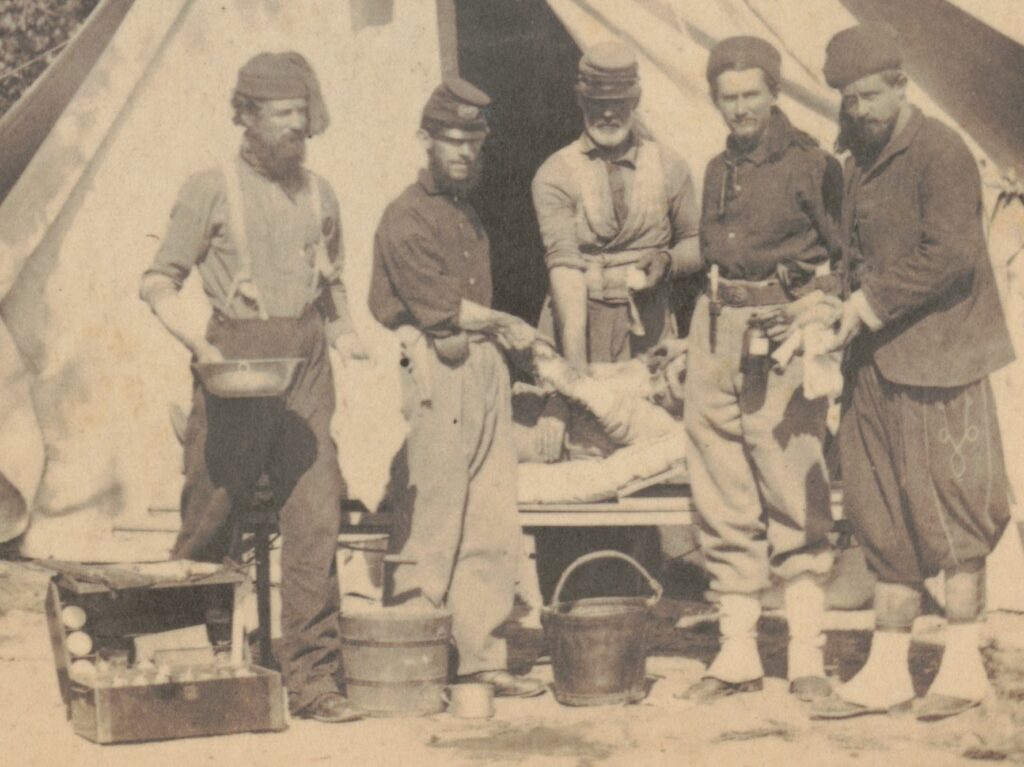

For the United States in the Civil War, their surgeons never had to. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion showed that roughly 99.68% of surgeries conducted by United States surgeons were done with some form of general anesthesia (chloroform, ether, or a combination of the two), and attributes the minute number of cases where it was not used to misguided objection by the surgeons rather than a want of supplies.[1] According to the late anesthetist Maurice Alban, the U.S. purchased one million ounces of chloroform and one million ounces of diethyl ether.[2] Breaking those down to the averages for each anesthetic agent if given pure,[3] it’s a minimum of 887,000 doses available throughout the conflict. This is due in large part to the very small doses required for general anesthesia. The authors of The Medical and Surgical History found that the average dose of chloroform was only 11 drachms, about three quarters of a shot glass. When supplies began to run lower after Antietam, Clara Barton was able to stave off disaster by delivering only ten pounds of chloroform to the army, which was apparently more than enough.

There were some surgeries that were performed without general anesthesia because it was medically inadvisable to do so. Anesthesia affects breathing, so any surgeons operating on any condition involving the lungs, throat, or mouth had to be very selective in how or if chloroform was used. One such case was that of Major Ephraim Cutler Dawes of the 53rd Ohio, whose jaw was shattered at the Battle of Dallas, Georgia. His aunt witnessed his painful reconstructive surgery several months later in a Cincinnati hospital: “He was an hour and a half under the surgeon’s knife and not under the influence of chloroform.”[4]

Civil War surgeons were operating without the benefit of Arthur Guedel’s classification, introduced in 1937, in which he introduced a detailed guide to the stages of anesthesia. These four stages are described in much more detail by Bilal A. Siddiqui and Peggy Y. Kim for the National Center for Biotechnology Information:

- Analgesia or Disorientation: “Patients are sedated but conversational.”

- Excitement or Delirium: “This stage is marked by features such as disinhibition, delirium, uncontrolled movements, loss of eyelash reflex, hypertension, and tachycardia.”

- Surgical Anesthesia: This is the targeted anesthetic level for procedures requiring general anesthesia.

- Overdose[5]

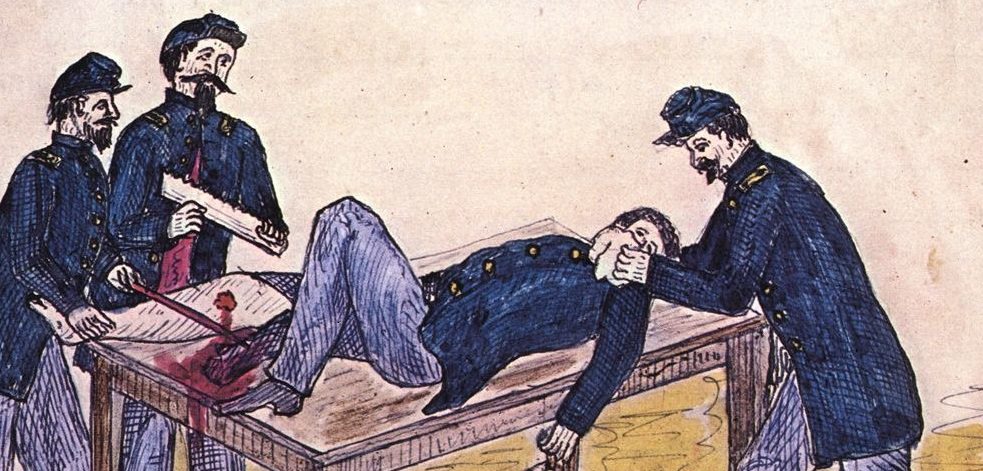

The second stage of Guedel’s classification was recognized in this era as the “excitement” phase, and it was often in this stage that surgery was actually performed. During the excitement phase there are numerous effects on the respiratory system. Again, from Kim and Siddiqui:

“Airway reflexes remain intact during this phase and are often hypersensitive to stimulation. Airway manipulation during this stage of anesthesia should be avoided, including both the placement and removal of endotracheal tubes and deep suctioning maneuvers. There is a higher risk of laryngospasm (involuntary tonic closure of vocal cords) at this stage, which may be aggravated by any airway manipulation. Consequently, the combination of spastic movements, vomiting, and rapid, irregular respirations can compromise the patient’s airway.”[6]

When operating with the throat and mouth, general anesthesia was avoided. General anesthesia can affect breathing, making an already complicated surgery more dangerous. Remember that Dawes’ surgery took an hour and a half. According to the authors of the Medical and Surgical History, “the average time in which insensibility was induced by chloroform was nine minutes, by ether and chloroform seventeen minutes, and by ether sixteen minutes.” Major Dawes would have had to be re-anesthetized at least six times over the course of his operation, an unacceptable risk for his condition.

The lack of guidelines for the use of anesthesia contributed to other potential complications. There’s good evidence for under dosing throughout the conflict, probably because of a fear of overdose and because there wasn’t an agreed upon system for monitoring patients as they slipped into an anesthetized state. This left a lot of leeway for surgeons to presume the way they’ve always done it was the correct way. This was true in both desperate circumstances where chloroform was running low (as will be discussed in part two), and in controlled circumstances where more anesthetic agents were widely available. Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson remembered the sound of the saw on his bone after his amputation,[7] meaning that he did not receive enough anesthetic agent to induce amnesia, though he did receive enough for muscle relaxation and analgesia.

In short, the visceral hospital scenes of Glory and Dances with Wolves are moving but ultimately fictional, because they portray surgical operations that would normally have been performed on an anesthetized patient, and they imply or explicitly say that well supplied U.S. forces ran out of chloroform.

In the second part of this post, we will look at the Confederate experience.

About the Author

Kyle Dalton is the Membership and Development Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is also a summa cum laude graduate of the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, where his paper Active and Efficient: Veterans and the Success of the United States Ambulance Corps was awarded the Zeender Prize for best history thesis. In his spare time Kyle writes and maintains a website on the lives of common sailors in the eighteenth-century: BritishTars.com.

Endnotes

[1] Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, Volume II, Part III, Washington Printing Office: 1883, page 887-898.

[2] Alban, Maurice, “The Use of Anesthetics During the Civil War,” in Pharmacy in History, Vol. 42, No. 3/4, 2000, pages 99-114.

[3] Medical and Surgical, Vol II, Part III, 887-898.

[4] Dawes, Rufus R., Service with the Sixth Wisconsin, Marietta, Ohio: E.R. Alderman & Sons, 1890, page 312, via HathiTrust Digital Library, accessed July 9, 2021, <https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006578837>.

[5] Siddiqui, Bilal A. and Kim, Peggy Y., “Anesthesia Stages,” StatPearls, March 7, 2021, via National Center for Biotechnology Information, accessed July 9, 2021, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557596/>.

[6] Siddiqui, Kim, “Anesthesia Stages.”

[7] Prof. R. L. Dabney, D.D., Life of Lieut. Gen. Thomas J Jackson, (Stonewall Jackson), New York: Blelock & Co., 1866, page 696, via Google Books, accessed February 26, 2020, <https://books.google.com/books?id=h7xcAAAAcAAJ>.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.