In Part One of this series, I examined the incidents of unanesthetized surgery on the Union side. This part examines the incidents in the Confederacy.

Shortages were endemic in the Confederate Medical Department, to be sure, but anesthetic agents almost always seemed to be around. Prominent Confederate surgeon Hunter Holmes McGuire claimed to have seen 28,000 operations under general anesthesia,[1] and his colleague J.J. Chisolm claimed an additional 10,000. Confederate surgeon Ferdinand Eugene Daniel summed up the broad situation nicely:

We were short on chloroform and had to use it as economically as possible-we had none to waste. We had to use such as we could get and could not be choice as to quality…. Some that we used I know was adulterated. I remember a lot that smelled like turpentine. Well, sirs, I want to tell you now that I administered chloroform and had it administered for me many scores of times, for all manner of operations and on all sizes and ages and conditions of men…I do think it remarkable when I recall the perfect abandon, the almost reckless manner in which it was given to every patient put on the table, almost without examination of the lungs or heart and without injury. I can only attribute it in part to the fact that it was given freely, boldly pushed to surgical anesthesia, and no attempt was made to cut till the patient was limber.[2]

It has often been said that the Confederacy ran out of chloroform after Antietam or Gettysburg, but we haven’t yet found any evidence for that. There are scattered reliable cases of capital amputations taking place throughout the conflict without anesthesia (about ten that we’ve tracked down), though not all are clearly from a lack of supply. When Edmund DeWitt Patterson of the 20th Georgia was operated on by his own cousin, he recalled “I wanted him to give me chloroform so that I would not suffer any more, but Frank said that it wasn’t best and that it would soon be over and would not be very painful, so I must ‘grin and bear it.'”[3] This could be a case of a lack of supply, excused by his surgeon/relative for some reason, or it could be that Dr. Patterson was an adherent of archaic and largely rejected medical opposition to anesthesia. Maybe there’s some yet unimagined motivation behind his decision if it was a decision at all. We can’t really say.

While we haven’t found anything for lack of Confederate chloroform at Gettysburg or Antietam, we did find a serious supply crisis earlier in the conflict: The Seven Days Battles from June 25 to July 1, 1862, just over a year into the conflict.

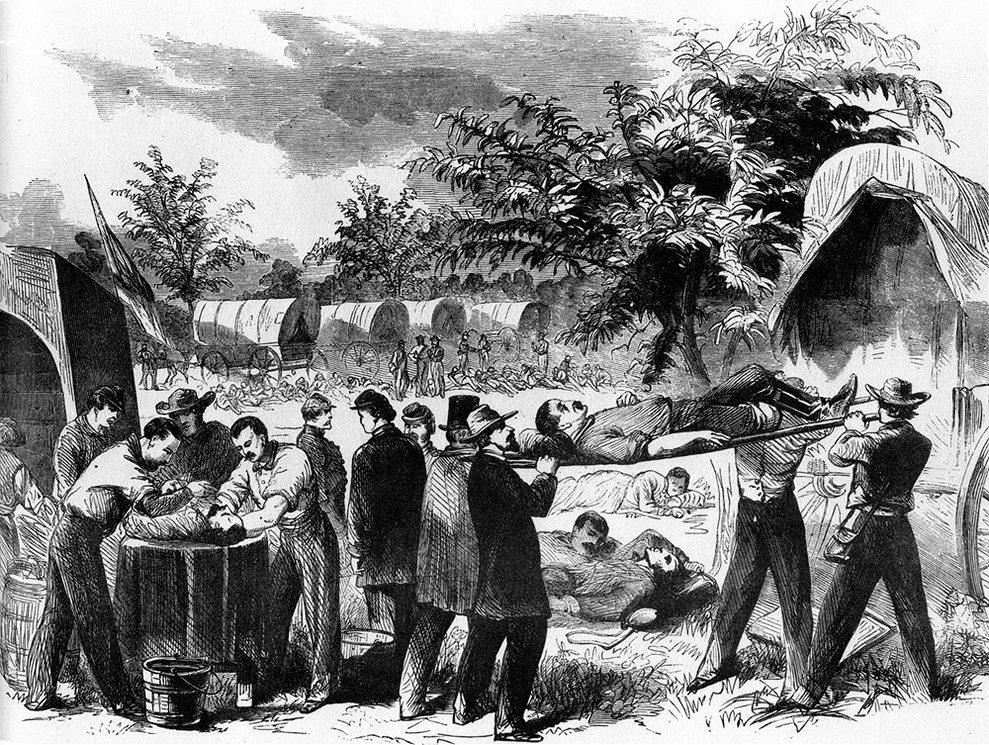

Rachel Frazier, a witness to the aftermath of White Oak Swamp, remembered that “the Confederates had our mess tent for their amputating tent, and having no chloroform, it was exceedingly painful to me to hear their poor soldiers’ screams when their limbs were taken off by that indefatigable surgeon, Dr. [Daniel Burr] Conrad.”[4] This lack of supply lasted for weeks after the battles. Private James Winchell of the 1st U.S. Sharpshooters was taken prisoner with a serious wound at Gaines Mill and would undergo amputation weeks later. “About noon July 1st, Surgeon White came to me and said: ‘Young man, are you going to have your arm taken off, or are you going to lie here and let the maggots eat you up.[‘] I asked if he had any chloroform or quinine or whisky, to which he replied ‘no, and I have no time to dilly-dally with you.[‘]”[5] Another prisoner, only shortly after being captured, was denied treatment by a Confederate surgeon, but witnessed his fellow prisoners “put under the influence of chloroform, but a number of them regained consciousness during the operation, and swore worse than the British army did in Flanders, as they writhed in their agony.”[6] While there was some chloroform available for those patients, it clearly wasn’t enough.

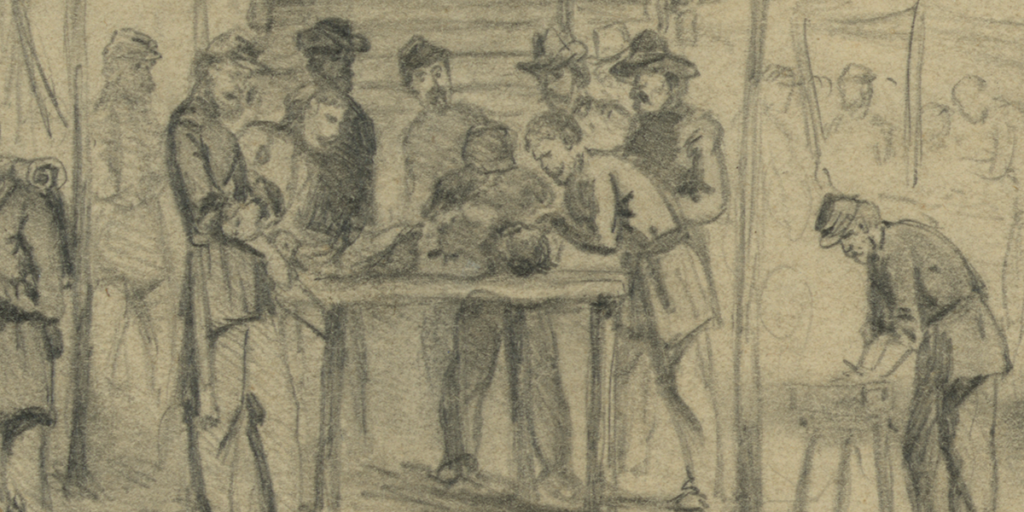

The lack was serious enough that high ranking officers would undergo serious operations without anesthesia. The most telling case is that of Lt. Col. William Brandon of the 21st Mississippi. Brandon was himself a doctor in civilian life, and his insight is key to understanding what was going on.

“[The surgeon] said there was no doubt of the propriety of an immediate amputation. I asked if he had chloroform, he said yes and proceeded. When I felt the tourniquet tighten on my leg, I called to him, I was not under the influence of chloroform. He said he had no more, & asked should he proceed? I replied ‘off with it!’ I supposed I could stand it. The operation was performed in an inconceivable short time, but the pain was horrible, particularly the tying up the arteries.”[7]

Brandon was surprised at the lack of chloroform, and his surgeon was clearly nervous about proceeding without it.

While there were occasional instances throughout the rest of the conflict where chloroform was not available to the Confederacy, they were few and far between. Perhaps at Vicksburg (though that may have been confined only to a lack of chloroform given to prisoners) and probably on a small scale following Second Manassas. Surprisingly, the Confederacy’s patients did not suffer the lack of chloroform at much larger battles like Gettysburg.

Before the Seven Days, the Confederate Medical Department constructed a laboratory for local production of medical supplies. After the Seven Days, a dozen more were built in a flurry of construction stretching across the length of the Confederate States from Virginia to Texas. It is unclear if they were constructed explicitly because of the debacle of Seven Days or if they were already planned. Regardless, with very few exceptions, general anesthesia would be widely available to the Confederate wounded for the rest of the conflict. That fear of a lack of supply remained, but strong and largely successful efforts were made to ensure their patients would be provided for.

In the words of one rebel surgeon: “Chloroform always agrees with children; it always agrees with women in labor, and it always agreed with the Confederate soldier. What connects these different classes together? A woman is not afraid of an anesthetic, nor is a child, and a Confederate soldier was afraid the chloroform would give out before it got to be his turn to be operated on.”[8]

[1] McGuire, Hunter M.D., L.L.D., “Annual Address of the President,” Transactions of the Southern Surgical and Gynecological Association, Volume II, Published by the Association, 1887, page 7, via HathiTrust Digital Library, accessed March 31, 2020, <https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hc>.

[2] Daniel, Ferdinand Eugene, Recollections of a Rebel Surgeon and Other Sketches: Or, in the Doctor’s Sappy Days, Chicago: Clinic Publishing Co., 1901, via Google Books, accessed July 24, 2020, <https://www.google.com/books/edition/Recollections_of_a_Rebel_Surgeon/z20UAAAAYAAJ>.

[3] Patterson, Edmund DeWitt, Yankee Rebel: The Civil War Journal of Edmund DeWitt Patterson, Kingsport, Tenn.: University of North Carolina, 1966.

[4] Frazier, Rachel, Reminiscences of Travel from 1855 to 1867, San Francisco, 1869, via Google Books, accessed June 17, 2021, <https://www.google.com/books/edition/Reminiscences_of_Travel_from_1855_to_186/RyxQABlJotoC>.

[5] James Winchell, “Wounded and a Prisoner,” appendix to Capt. C.A. Stevens, Berdan’s United States sharpshooters in the Army of the Potomac, 1861-1865, St. Paul, Minnesota: Price-McGill Company, 1892, via Internet Archive, accessed February 27, 2020, <https://archive.org/details/berdansunitedsta00stev>.

[6] Roy, Andrew, Recollections of a Prisoner of War, Columbus, OH: J.L. Trauger Printing Co., 1905, page 30, via Google Books, accessed June 25, 2021, <https://www.google.com/books/edition/Recollections_of_a_Rebel_Surgeon/z20UAAAAYAAJ>.

[7] Brandon, William L., military reminiscences of Brandon, J.F.H. Claiborne Papers, 1797-1884, The Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, accessed June 18, 2021, <https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/00151/>.

[8] Gordon C.P., M.D., “General Anesthesia by Chloroform or Ether, Which? Local Anesthesia by Cocaine or Eucaine, Which? General or Local Anesthesia in Enucleation or Extirpation of the Eye, Which?” in The Railway Surgeon, Vol. V., No. 11, October 18, 1898, page 246, via Google Books, accessed July 7, 2021, <https://www.google.com/books/edition/Railway_Surgeon/FTugAAAAMAAJ>.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.