Table of Contents

From the beginning of the war, enslaved people fled to Union lines from their enslavers. Some were returned by Union officers, while others were embraced and protected on an arbitrary basis. White Northerners debated what the government should do with the “contrabands” for the first two years of the Civil War. Out of this chaos the federal government adopted a policy in which enslaved people were treated as “contraband of war”: property that could be used to support the rebellion that the government seized. This granted a degree of freedom and protection to enslaved people, even though it failed to answer the long term question of their status when the war came to a close.

Several journalists suggested that contrabands be enlisted as stretcher bearers and ambulance drivers. Robert Dale Owen, in a letter in the Daily Evansville Journal entitled “The Cost of Peace,” made a typical argument:

It is to be admitted that African loyalty in this war will little avail us, if we have not good sense and good feeling enough properly to govern the negroes who may enter our lines. To render their aid available, in the first place we must treat them humanely-a duty we have yet to learn; and secondly, both for their sakes, and our own, we must not support them in idleness. Doubtless, they are most efficient as laborers, as domestics in camp, as teamsters, or employed on entrenchments and fortifications, or in ambulance corps, or as sappers and miners; or, as fast as Southern plantations shall fall into our possession, as field-hands. [1]

Many writers, were patronizing and fully embraced the stereotype of the lazy contraband. This was certainly the case in The New York Herald:

The subalterns and men of the ambulance corps might be profitably selected amongst the able-bodied contrabands who are now living like drones at the expense of the country. [2]

Many men of color were already risking their lives in battlefield medical evacuation, a fact many journalists were ignorant of or willfully ignored. The Newbern Weekly Progress reported one such instance at the Battle of Antietam:

We heard of three negro ambulance drivers who were spirited away by the rebels while we were on the battle-field. [3]

Those drivers almost certainly lost their freedom in the battle that would prompt the Emancipation Proclamation. That declaration, along with the establishment of the United States Colored Troops, ended the debate over how the government might employ contrabands. The day after Lincoln announced he would issue the Proclamation, a writer of The Rutland Weekly Herald put it bluntly:

The question is mooted at Washington whether men of African descent, if they are not allowed to fight for the Union which frees them, may not at least be organized into regular ambulance corps, to serve in carrying the wounded from the field and in burying the dead. [5]

Many USCT soldiers were detailed to the Ambulance Corps, and continued to risk their lives to save others. Captain Garth W. James of the 54th Massachusetts was grievously wounded in the legendary assault on Battery Wagner. He personally attested to the bravery of black stretcher bearers and the danger they faced:

Some ambulance men from my own regiment, with an empty stretcher, passed me while stampeding to the rear. They placed me on the stretcher; consciousness to me was fast playing itself out. Only one distinct recollection I now possess, and that was after being borne for a distance to the rear, and still under the mercy of Wagner’s fitful guns, a round shot blew off the head of the stretcher bearer in my rear producing a horrible and instant death. [6]

Surgeon George Otis vividly remembered his treatment of a black stretcher bearer wounded in combat:

Private C. Hamilton, Co. H, 3d Regiment, U.S. Colored Troops, while employed as a stretcher bearer, in carrying a wounded man from the field, during the assault on Port Hudson, Louisiana, June 14th, 1863, was struck by a musket ball, which passed through the upper part of his left thigh. The missile entered behind, near the gluteal fold, and, having fractured the upper part of the femur badly, passed out in front, in close proximity to the track of the femoral artery. He was taken to his regimental hospital…it was determined that amputation at the hip-joint afforded the only chance of preserving the man’s life. The operation was immediately performed…He expressed great gratitude for the operation, declaring that it had entirely relieved him of his excessive suffering. He rallied and appeared, for forty-eight hours after the operation, to be in a very hopeful condition. Then the vital powers seemed to flag. Thenceforward he sank gradually, and died from exhaustion, June 29th, 1863, four days after the operation. [7]

Careful medical treatment was not guaranteed if black soldiers fell into rebel hands. Illinois cavalryman John McElroy remembered when black soldiers who survived Olustee Station were brought to Andersonville:

The wounded were turned into the Stockade without having their hurts attended to. One stalwart, soldier Sergeant had received a bullet which forced its way under the scalp for some distance, and partially imbedded itself in the skull, where it remained. He suffered intense agony, and would pass the whole night walking up and down the street in front of our tent, moaning distressingly. The bullet could be felt plainly with the fingers, and we were sure that it would not be a minute’s work, with a sharp knife, to remove it and give the man relief. But we could not prevail upon the Rebel Surgeons to even see the man. Finally inflammation set in and he died. [9]

Another survivor of Andersonville named Warren Lee Goss testified before Congress after the war that USCT prisoners “were victims of atrocious amputations performed by rebel surgeons…when there had been a case of amputation, it had been performed in such a manner as to twist and distort the limb out of shape.”[8]

Another vital reason to evacuate wounded black soldiers were the massacres perpetrated by rebel soldiers incensed at “servile insurrection.” Such was the case at Milliken’s Bend, Fort Pillow, Plymouth, Saltville, The Crater, Poison Springs, Olustee Station, and many other battles. [9] It was for this reason that Surgeon Heichhold of the 8th U.S. Colored Infantry “was particular in collecting the colored troops who were wounded, and placed them in his ambulances and pushed on for a place of safety. Some one thought the white troops should be brought away also; but Dr. H. said: ‘I know what will become of the white troops who fall into the enemy’s possession, but I am not certain as to the fate of the colored troops.’” [10]

Not all USCT regiments were equipped to safely evacuate wounded soldiers. Colonel James Brisbin of the 6th U.S. Colored Cavalry wrote in his official report:

“Nearly all the wounded were brought off, though we had not an ambulance in the command. The negro soldiers preferred present suffering to being murdered at the hands of cruel enemy. I saw one man riding with his arm off, another shot through the lungs, and another shot through both hips. Such of the colored soldiers as fell into the hands of the enemy during the battle were brutally murdered. The negroes did not retaliate, but treated the rebel wounded with great kindness; carrying them water in their canteens and doing all they could to alleviate the sufferings of those whom the fortunes of war had placed in their hands.” [11]

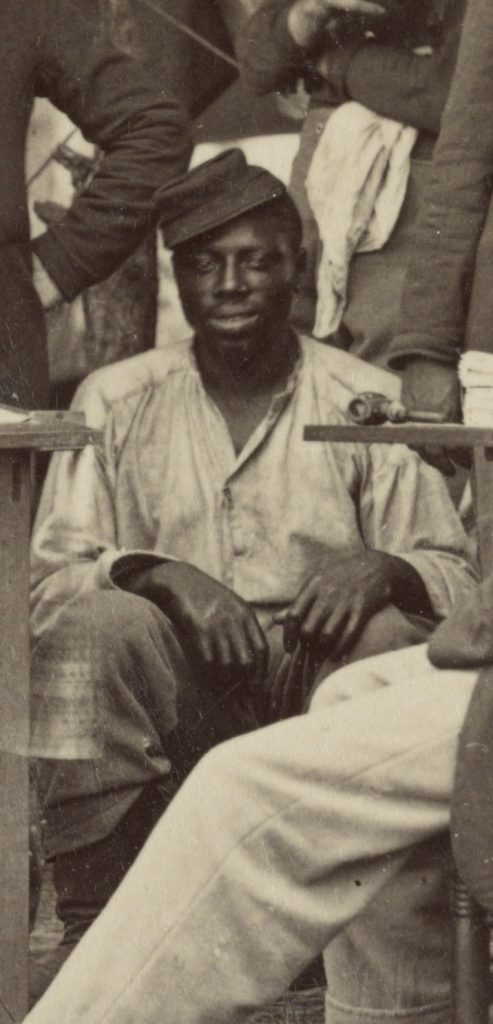

![Detail from "Fredericksburg, Va. Burial of Union soldiers," May [19 or 20], 1864, Library of Congress.](/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Fredericksburg-Va.-Burial-of-Union-soldiers-May-1864-LoC-jpeg-1024x810.jpg)

All ambulance drivers and stretcher bearers in the Civil War faced extremely dangerous conditions. Casualties were high and conditions difficult. Black men engaged in medical evacuation faced the added threat of re-enslavement or summary execution, along with the disdain of their white comrades. Despite these obstacles they persisted and saved countless lives. Their story has been little explored and is worth more attention. You can learn more at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, where we tell the stories of medical innovation and courage in the deadliest era in our nation’s history.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

Sources

[1] Owen, Robert Dale, “The Cost of Peace,” The Daily Evansville Journal, December 3, 1862, page 1, column 5.

[2] “Our Ambulance System,” The New York Herald, July 16, 1862, page 6, columns 4-5.

[3] “Incidents and Appearance of the Battlefield,” The Newbern Weekly Progress, Newbern, North Carolina, September 13, 1862, page 1.

[4] Beecher, Herbert W., History of the First Light Battery Connecticut Volunteers, 1861-1865, Volume 1, New York: A.T. De La Mare Ptg. and Pub. Co. Ltd., 1901, page 306.

[5] The Rutland Weekly Herald, September 25, 1862, page 5, column 2.

[6] James, Garth W., “The Assault on Fort Wagner” in War Papers Read Before the Commandery of the State of Wisconsin, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, Volume 1, quoted on IronBrigadier.com, accessed June 12, 2019, <https://ironbrigader.com/2013/05/09/captain-garth-w-james-54th-massachusetts-recalls-assault-fort-wagner/>.

[7] Otis, George A., Excisions of the Head of the Femur for Gunshot Injury, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1869, page 109.

[8] The Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives, Made During the Third Session of the Fortieth Congress, 1869, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1869, page 72.

[9] For more on racially motivated war crimes, see Urwin, Gregory J., Black Flag Over Dixie: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in the Civil War, Southern Illinois University, 2005; and Burkhardt, George S., Confederate Rage, Yankee Wrath: No Quarter in the Civil War, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2007.

[10] Letter from Sgt. Rufus S. Johns of the 8th U.S. Colored Troops to The Christian Recorder, quoted in A Grand Army of Black Men: Letters from African-American Soldiers in the Union Army 1861-1865, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992, page 42.

[11] Col. James S Brisbin to Brig. Gen. L. Thomas, 20 Oct. 1864, vol. 39, Union Battle Reports, series 729, War Records Office, Adjutant General’s Office, Record Group 94, National Archives, via Freedmen & Southern Society Project, University of Maryland, accessed June 11, 2019, <http://www.freedmen.umd.edu/Brisbin.html>.

[12] See Urwin, Black Flag, and Burkhardt, Confederate Rage.

[13] Dyer, J. Franklin, The Journal of a Civil War Surgeon, Michael B. Chesson editor, Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2003.

About the Author

Kyle Dalton is a summa cum laude graduate of the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, where his paper Active and Efficient: Veterans and the Success of the United States Ambulance Corps was awarded the Zeender Prize for best history thesis. In his spare time Kyle writes and maintains a website on the lives of common sailors in the eighteenth-century: BritishTars.com.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.