Table of Contents

Many medical schools and professionals before, during, and after the Civil War relied on African Americans for the service their bodies could provide to the field. As thousands of individuals fell ill or suffered from wounds during the Civil War, medicine had to adapt quickly. Surgeons lacked a deep understanding of Germ Theory, supply lines were often unreliable, and the need for rapid medical development necessitated experimental treatments and decisions. In this environment, a medical system which was accustomed to using African American bodies for medical experimentation and anatomical dissection turned to them anew for vaccine material, while ignoring their health and wellness.

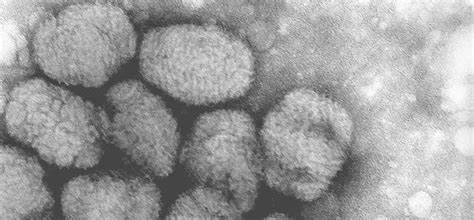

Infectious disease proved to be the largest killer of the Civil War, and diseases like smallpox, malaria, and measles took a toll on both armies. However, smallpox was one of the few diseases for which effective prevention strategies were already in use. While a practice known as inoculation, through which doctors injected a mild form of the disease into healthy individuals, had been widespread since the 1720s, Edward Jenner invented a safer vaccination, made from cowpox, in 1798. Medical and government professionals were also aware of preventive measures, such as quarantine, isolation, and the destruction of infected clothes, which could drastically reduce the spread of the disease.[1]

Although vaccination existed and was widely accepted, and despite vaccination requirements in both the Union and Confederate armies, there were often complications in how effectively vaccines were administered. While both armies saw the need to curb the spread of smallpox among large groups of soldiers, this was the first time many doctors in the South were encountering vaccination. To conduct vaccination on this large scale, both armies needed a large amount of vaccine material, but the Northern blockade of the South prevented the import of this matter. As a result, Southern doctors often turned to children and African Americans to collect vaccine matter: children were considered healthy subjects, and enslaved populations were easily accessible.

This was not the first time Black bodies had been used as resources in the medical field: for years, medical schools and researchers in the North and the South had relied on Black bodies more extensively than their White counterparts. Anatomical dissections and experimentation required the use of human subjects and formed an important part of medical education in the antebellum period. By using the bodies of marginalized groups, especially at a time when human anatomical dissection was illegal in many places, medical schools were able to avoid the legal repercussions of dissecting members of the White elite class. Grave robbing was common in this period before the dissection of unclaimed corpses was legalized, which did not occur in some states until the 20th Century. African American cemeteries, like the Mt. Zion Cemetery in Washington, DC, were often the targets of grave robbers, and doctors continued to view Black bodies in medicine as increasingly dehumanized.[2]

So, as the war necessitated the harvesting of vaccine material, Southern doctors turned to Black populations. Surgeons would create a small cut on the child’s arm, inject lymph from a previously vaccinated patient, wait for the child to develop a fever, blisters, and pustules, and then slice into these pustules to harvest new lymph. These subjects, often African American children, were left with scars from the operation, a lasting symbol of their exploitation.[3] Complications often occurred, such as when the vaccine “didn’t take,” caused severe illness, or even led to death. Issues in administration, but also in the source of vaccine matter could lead to these complications. For example, syphilis began to spread among soldiers who were vaccinated for smallpox, an adverse result that stemmed from harvesting vaccine material from syphilitic pustules. Issues like these only further encouraged the use of children for vaccine matter, to avoid the possibility of harvesting infected material.[4]

The Civil War created a unique environment in which large populations of soldiers were on the move and grouped together, exposed to germs and in need of vaccination. Simultaneously, after President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, large populations of African American refugees migrated to escape the South. Freed populations of colored troops and refugees suffered from outbreaks of smallpox, from which they faced disproportional illness and mortality rates. Thousands of freed people escaped from Confederate states to Union lines and often crowded along the outskirts of Union army camps. Most refugees had only the clothes on their back, found no reliable shelter or food, and lived in unsanitary conditions.[5] As a result, when they fell ill – and they often did – African American refugees often just became sicker and died. While on the run, freed slaves were also separated from their prior networks of kin and community, meaning any folk remedies that may have been useful, whether the care of relatives or use of plants from personal gardens, were no longer available.[6]

Some surgeons, such as Alexander T. Augusta – the first African American surgeon commissioned by the US Army – reported on these environmental factors, like lack of resources and unhealthy conditions, that impacted the health of Black populations. However, most medical thinkers accepted the theory that the Black population was headed for extinction anyway, rather than consider the environmental factors impacting their health.[7] A supposed, innate physiological difference between White and Black people simultaneously justified the use of African American bodies for vaccine matter and the denial of their medical experiences during the Civil War. The unprecedented need for mass vaccination allowed Union and Confederate surgeons to study its effects and complications on a wide scale, something that did contribute to improvements in epidemiology, but this relied on the imbalance of power between White and Black populations.

About the Author

Rebecca Ruggles is a rising junior at Gettysburg College, and the Willen Intern at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine for the summer of 2024. She is pursuing a Bachelor of Arts in History with a minor in Educational Studies, along with her Teacher Certification for secondary social studies.

Sources

[1] Reimer, Terry. “Smallpox and Vaccination in the Civil War.” Surgeon’s Call, (Winter 2004). https://civilwarmed.321staging.com/surgeons-call/small_pox/.

[2] Willoughby, Christopher. “Training on Black People’s Bodies.” In Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2022. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezpro.cc.gettysburg.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=3407112&site=ehost-live. Meier, Allison C. “Grave Robbing, Black Cemeteries, and the American Medical School.” JSTOR Daily. August 24, 2018. https://daily.jstor.org/grave-robbing-black-cemeteries-and-the-american-medical-school/.

[3] Downs, Jim. “‘Sing, Unburied, Sing:’ Slavery, the Confederacy, and the Practice of Epidemiology.” In Maladies of Empire: How Colonialism, Slavery, and War Transformed Medicine. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2021. Accessed June 4, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central.

[4] Downs, Jim. “‘Sing, Unburied, Sing:’ Slavery, the Confederacy, and the Practice of Epidemiology.” In Maladies of Empire: How Colonialism, Slavery, and War Transformed Medicine. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2021. Accessed June 4, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central.

[5] Downs, Jim. “Dying to Be Free: The Unexpected Medical Crises of War and Emancipation.” In Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezpro.cc.gettysburg.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=442355&site=ehost-live.

[6] Downs, Jim. “Dying to Be Free: The Unexpected Medical Crises of War and Emancipation.” In Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezpro.cc.gettysburg.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=442355&site=ehost-live.

[7] Downs, Jim. “Reconstructing an Epidemic: Smallpox among Former Slaves, 1862-1868.” In Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezpro.cc.gettysburg.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=442355&site=ehost-live.