Table of Contents

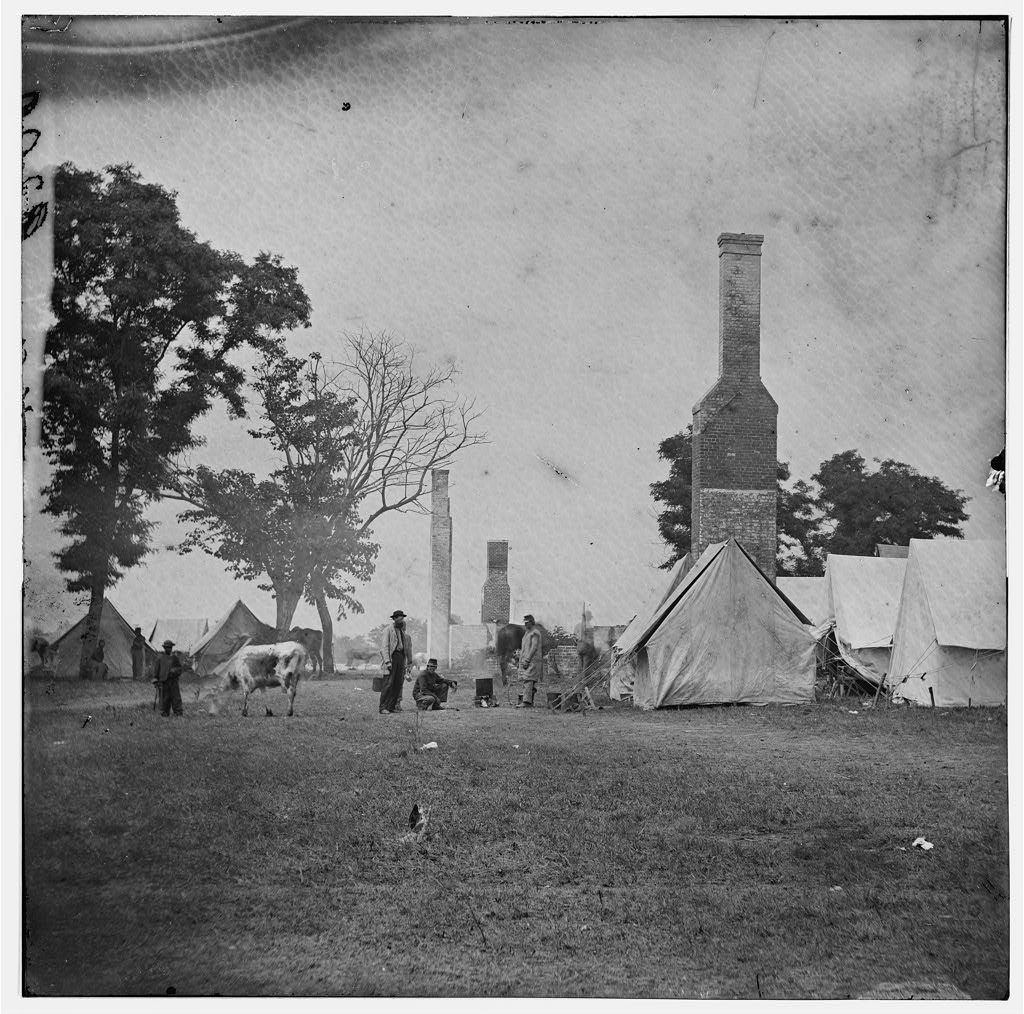

Dawn was breaking over the Pamunkey River on the morning of June 20, 1864, but Union pickets still struggled to see through the thick fog that had settled over the humid Virginia landscape overnight. Parked around the ruins of “White House” behind them—originally the homestead of Martha Custis Washington and burned to the ground by the Army of the Potomac in June 1862—were hundreds of wagons loaded with 150,000 rations for Grant’s ongoing operations in Virginia. Suddenly, a shot rang out through the thick air. Then another, and another. Voices cried out warnings that Confederate cavalry were approaching the camp, and the pickets panicked. With seasoned Southern soldiers hot on their heels, the Union pickets scampered back toward the main line surrounding the wagon park.

Since the Army had declared many of these men unfit for active field service, one can hardly blame them for not wanting to fight a pitched battle against Confederate cavalry. Included in the White House Landing garrison that morning was the 18th Regiment of the Veteran Reserve Corps. Originally named the Invalid Corps, the War Department established this organization for men no longer able to serve in the field—those who had been permanently disabled by wounds or disease contracted in the line of duty but could still serve the army in valuable capacities, such as in garrison, as military police, or on clerk duty. This freed as many able-bodied soldiers as possible for frontline service.

The Corps was organized into two battalions; the First was for men who could shoulder a musket and do garrison duty, while the Second consisted of those who were theoretically so severely injured or disabled (such as amputees) they could not carry a weapon. By October 1863, the Invalid Corps was composed of sixteen regiments. Although each regiment was supposed to be constituted of six companies of the First and four companies of the Second Battalion, this organization was not always adhered to in the field.

Throughout its first year, the soldiers of the Invalid Corps (renamed the Veteran Reserve Corps in March 1864 because “invalid” solicited jeers and sarcasm from field troops) did admirable service in guarding prisoners, pursuing and arresting deserters, and escorting new recruits to the front. But as Grant’s Overland Campaign kicked off in the spring of 1864, the army asked one regiment to go above and beyond. On May 11, the six Second Battalion companies of the 18th Regiment, under the command of Colonel Charles F. Johnson (formerly of the 81st Pennsylvania Infantry), departed Washington for Belle Plain, Virginia. There, at a supply depot for the Army of the Potomac, the ten officers and 514 men of the regiment were to guard Confederate prisoners captured during the fierce fighting at Wilderness and Spotsylvania. They remained there until May 24, when Grant’s aggressive shifts southward necessitated moving the base of supplies to Port Royal, on the Rappahannock River.

Most of the regiment, being unfit for sustained marching, embarked on a transport for the roundabout trip down the Potomac River to the new supply depot. Colonel Johnson led the remainder of the regiment, about 150 of the most capable men, overland on foot. The twenty-five mile march was brutal for the VRC soldiers. Johnson and his officers “coaxed the men on” and “ordered, pleaded, persuaded, [and] reasoned with the poor fellows who dropped by the roadside.” When the sorry contingent finally arrived in Port Royal, only about forty of them were able to answer roll. Colonel Johnson believed the march was “a damn outrage and in direct opposition to all the pledges of the Government in reference to the Corps,” and that it was pure “nonsence [sic]…to put such men out here.” The regiment only spent four days at Port Royal before again sailing south (luckily, all of the regiment this time) to White House Landing, on the Pamunkey River.

Colonel Johnson was furious over his regiment’s unexpectedly strenuous duties. “I feel very indignant as this Corps ‘organized for Provost Guards and Guards in Cities’ of ‘men not fit for the field’ but ‘fit only for such service’,” he complained in a letter to his wife, “should be sent to this infernal spot.” Despite the challenges, the officers and men of the regiment still performed their duties to the utmost of their physical abilities while at White House. Johnson posted those men unable to stand or walk for lengthy periods to supervise shipping operations at the landing, while the more able-bodied men guarded rebel prisoners and hospitals, as well as quartermaster, commissary, and Sanitary Commission stores.

Although Colonel Johnson was for a time in overall command of several volunteer regiments stationed at White House, by June 15 most of them had departed. This left only a skeleton force to guard a stockpile of rations and wagons supposedly intended for Maj. Gen. David Hunter and his forces in the Shenandoah Valley. “If he [Hunter] does not hurry up,” Johnson fretted, “the Rebs will discover our small command and make us hurry up, probably a little faster than comfortable.”

Johnson was right; things got uncomfortable for the 18th Regiment in a hurry—which brings us back to the Union pickets on the morning on June 20. Under a cover of thick fog, a division of Confederate cavalry under Wade Hampton made a stab at the rations stockpiled at the Landing. The first indication of the attack was a ragged volley from the pickets, who immediately turned tail and ran back to the main line of rifle pits. Colonel Johnson, who had not been in combat since Antietam, relished his return to the vortex of battle. “I immediately mounted my horse and lead [sic] (for they [the pickets] would not go back at first) back to their post,” the colonel recounted to his wife. “Again the Rebs drove us back and again I lead [sic] them on.” The fighting raged back and forth for about a half an hour, when the heavy fog finally lifted. Johnson found the Confederates still in possession of his picket line, so he ordered his artillery—Capt. Christian Woerner’s 3d New Jersey Battery—to open up, driving the attackers back into the woods. The heavy skirmishing continued throughout the morning, with Colonel Johnson personally leading a counterattack to retake the picket line. Twice during the engagement, an aide to Brig. Gen. John J. Abercrombie (in overall command of the garrison) rode up to Johnson and asked him if his Veteran Reserve Corps soldiers would hold. “Tell the general,” the colonel supposedly replied, “that my men are cripples, and they can’t run.” By around noon, Hampton’s horsemen had had enough, and retired. Casualties were fortunately light; only one man in the 18th Regiment was wounded.

The skirmish at White House Landing was the climax of the 18th Regiment’s field service that spring. The next day, Johnson and his tired soldiers boarded a steamer to make their way back to Washington. The VRC soldiers back in the capital lauded the men of the 18th as “the war torn veterans,” and Johnson told his wife that he was introduced to “scores of officers” as the “Hero of the White House.” The other garrison soldiers “appear[ed] to be tickled at the idea that 2000 men under an ‘Invalid’,” Johnson boasted, “should repulse between 5 and 6000 picked troops under such leaders as Hampton and Fitz Hugh Lee.” The colonel furthermore hoped “to Heavens that the Government is satisfied with sending Sick men to the front.” But he was still proud of their service. “I am not sorry that I went,” he wrote, “because the Vet. Res. Corps under my command were the first if not the only ones that have been under fire.”

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

Sources

Pelka, Fred, ed. The Civil War Letters of Colonel Charles F. Johnson, Invalid Corps (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2004), pp. 227–249.

U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, ser. 1, vol. XXXVI (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1889), pp. 747–749.

Ibid, ser. 3, vol. V, pp. 543–567.

About the Author

Nathan Marzoli is a historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History in Washington, D.C., where he specializes in unit history and leads staff rides to Civil War battlefields. He has a BA and MA in History from the University of New Hampshire. His publications include “‘Their Loss Was Necessarily Severe:’ The 12th New Hampshire at Chancellorsville,” and “‘We Are Seeing Something of Real War Now:’ The 3d, 4th, and 7th New Hampshire at Morris Island, July-September 1863” (winner of the 2017 Army Historical Foundation’s Distinguished Writing Award). He is currently working on a study of substitutes in the Union army.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.