Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

On November 28, 1864, Surgeon Thomas A. McParlin finally finished off his lengthy after-action report on the Battle of the Wilderness which was fought on May 5 -7. It had been a long five months for McParlin, his odyssey beginning when he was appointed Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac on January 14, 1864, replacing the revolutionary reformer Jonathan Letterman.

McParlin’s first task was monumental – to prepare the medical department for an upcoming campaign that would push its capabilities further than ever before. The “Overland Campaign” would see Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant against Confederate General Robert E. Lee in forty days of combat in Virginia between the Rapidan and James Rivers. Thanks to the foundation laid by Letterman and the adoption of his plan by Congress on March 11, 1864, McParlin was able to quickly and efficiently prepare the medical department for this overwhelming task. By the end of April 1864, the department was fully organized and equipped to service the army until June and to care for 20,000 wounded.

Thus the medical department stood prepared when the first fight of the campaign, the Battle of the Wilderness, erupted on May 5, 1864. Fought in the midst of a thicket of dense trees and tangled underbrush on abandoned farmland near the old Chancellorsville battlefield, it was known as the battle “which no man saw or could see.”[1] Artillery proved almost useless in such conditions and the battle raged for two days as a series of attacks and counterattacks across a strip of ground roughly a mile wide, pitting soldiers against one another in very close proximity.

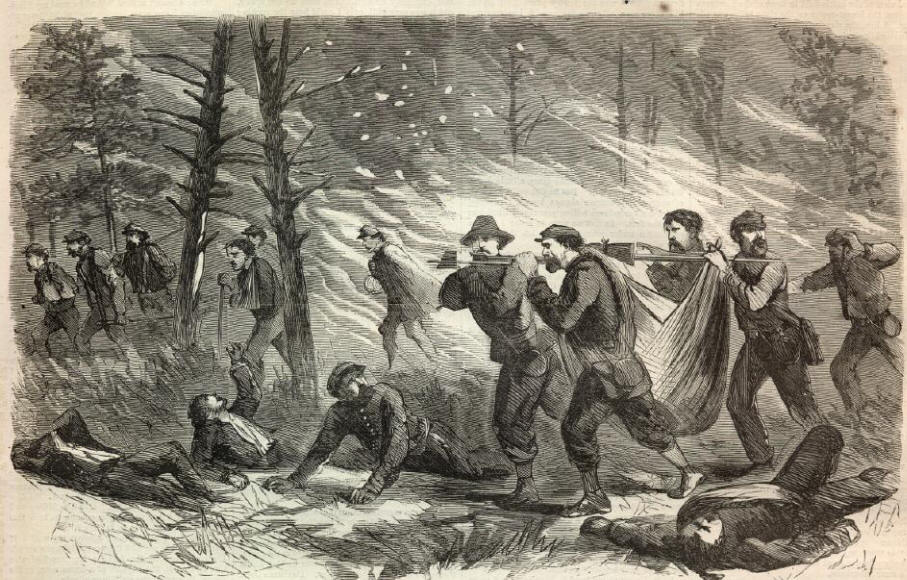

“A red volcano yawned before us and vomited forth fire, and lead, and death,” Theodore Gerrish, a private in the 20th Maine, later wrote. “What a medley of sounds. The incessant roar of the rifles; the screaming of bullets; the forest on fire; men cheering, groaning, yelling, swearing and praying!”[2] Stretcher-bearers struggled to remove the wounded the best they could in this chaos, but unfortunately many were left stranded on the battlefield. Adding to the horror, brush fires erupted from bullets and shells, leaving the wounded to suffocate or burn to death in the flames. There is no exact count of how many perished in this manner, but McParlin estimated it to be around 200.[3]

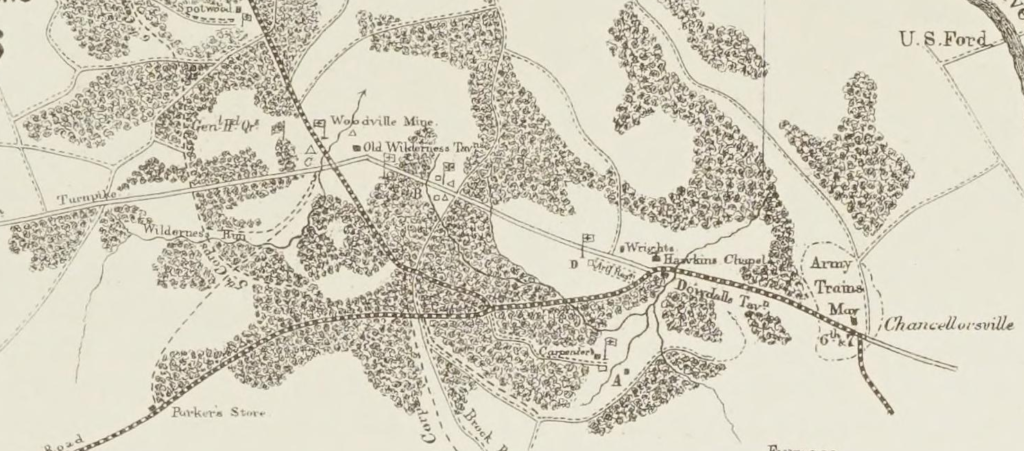

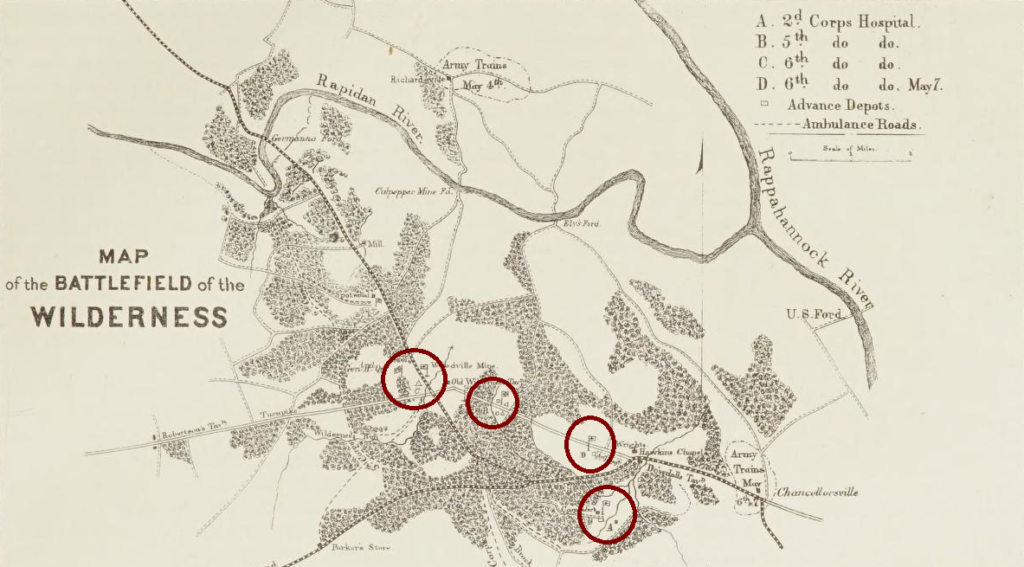

Amidst the chaos, the medical department worked feverishly, and efficiently to care for the wounded. Ambulances stationed near the Fredericksburg turnpike, roughly 400 yards behind the line of battle, transported the wounded to the field hospitals (each within two miles of the front), which awaited their arrival fully staffed and stocked with supplies – so well stocked in fact the medical purveyor further behind the lines at Woodville Mine never received any requests for additional supplies.

The Fifth Corps field hospitals, located on a slope of open ground by a small creek which crossed the Fredericksburg Pike one mile east of Old Wilderness tavern, treated 1,235 soldiers in the span of nine hours.

The Sixth Corps field hospitals were scattered at various points along the Germania Ford turnpike, and treated about 1,000 patients. Enemy fire the evening of May 6th forced the Sixth Corps hospitals to move to the vicinity of Dowdall’s tavern near the Fredericksburg turnpike on the opposite end of the battlefield – luckily, the only casualties were two ambulances.

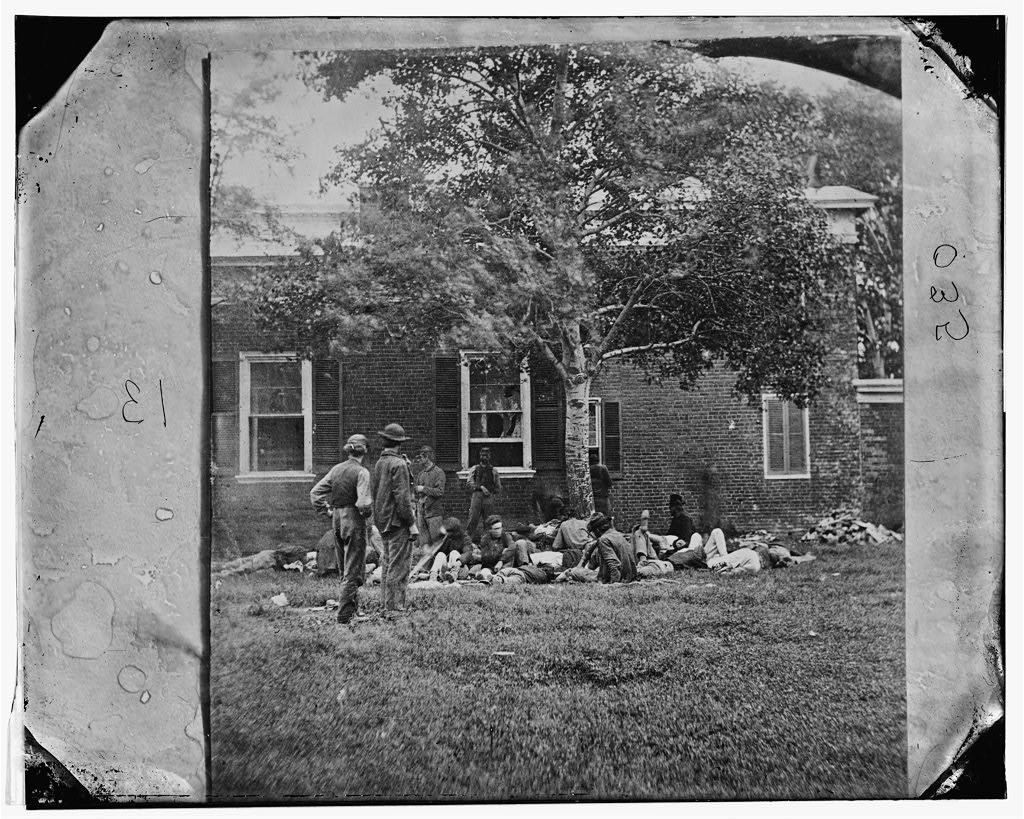

The closest hospitals to the front, that of the Second Corps, were located near the Carpenter House, one mile south-east of the new Sixth Corps hospital at the junction of the Germanna Ford and Chancellorsville plank-roads. About 600 wounded were tended to there, 120 of which were Confederates.

The majority of the roughly 9,000 wounded suffered from gunshots and only around 240 from cannon shot and shell. According to the chief ordnance officer only eleven rounds of ammunition per soldier were used for the entire two-day battle – a testament of the close quarters fighting wrought by this conflict.

On the morning of May 7th, Major General Meade ordered all the wounded sent to Rappahannock Station for transport to Washington. Loaded into trains, wagons and ambulances, they were made as comfortable as possible for their long trip to the general hospitals. However, 960 were left behind in the field hospitals because there was no room to transport them– 660 Union and 90 Confederates in Second Corps hospitals, 200 Union and 4 Confederates in the Fifth Corps hospitals and 100 Union in the Sixth Corps hospitals.

Tents, attendants, medicines, stores, dressings, and rations were also left behind. On May 8th, Meade changed the destination to Fredericksburg due to the changing course of the army, and the whole city was quickly converted into a hospital for wounded Union soldiers. Over the next two weeks, the army retrieved the wounded from the battlefield and conveyed them to Washington, while those left in the care of the Confederates were slowly extracted. The last forty-five were retrieved on June 8, 1864.

According to McParlin’s report, there were 15,004 total casualties: 9,102 wounded, 2,009 killed and 3,893 missing over the course of the two-day battle. While it ended in a stalemate, the Union army’s steady southern trajectory put continual pressure on the Confederacy that set the stage for Southern defeat the following year. Thanks largely to Letterman’s plan established during the Maryland Campaign of 1862, medical care in the aftermath of the Battle of the Wilderness stood in a far superior position than it had in earlier years. Fully supplied, stocked and ready to treat the wounded as the battle raged, the Medical Department in 1864 saved countless lives during that horrific bloody battle in May of 1864.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Rachel Moses is the Site Manager for the Pry House Field Hospital Museum. She received her M.A. in History and Museum Studies from Youngstown State University in Ohio. She most recently worked as an Education Specialist for the West Virginia State Museum in Charleston, WV from 2011 to 2018.

Endnotes

[1] https://archive.org/details/medicalsurgicalh11unit/page/150/mode/2up/

[2] https://www.google.com/books/edition/Army_Life_in_Chamberlain_s_20th_Maine_Ex/bytpCwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=A+red+volcano+yawned+before+us+and+vomit+forth+fire,+and+lead,+and+death&pg=PT96&printsec=frontcover

[3] https://archive.org/details/medicalsurgicalh11unit/page/150/mode/2up/