Table of Contents

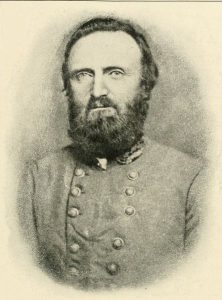

One spring day – May 25, 1862, to be exact – Confederate surgeon and medical director Dr. Hunter McGuire jubilantly entered his hometown of Winchester, Virginia with General “Stonewall” Jackson as the gray-clad soldiers pushed the Union occupiers commanded by General Nathaniel P. Banks out of town. The Union troops left behind a treasure-trove of supplies: clothing, food, delicacies, weapons, ammunition, and medical supplies. There were more medical supplies than Hunter McGuire had seen in one place since the beginning of the war, maybe even in his entire life.[i]

Along with the captured medical supplies, seven Union doctors fell into Confederate hands. Apprised of their plight, McGuire approached his commanding general. That day the town of Winchester stood at the literal crossroads of history. Militarily, it occupied a significant turning point in Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign. Socially, it liberated the mostly pro-Southern town from “Yankee” rule. Medically, it presented an opportunity to help define how captured military doctors and nurses should be treated, ensuring more consistent care for the sick and injured.

During the Civil War, battlefield evacuation of the wounded became a systemized process for the first time. Both North and South constructed military hospitals. The common practice of anesthetic use brought relief from surgical pain unknown in previous eras. New medicines came into use and staple tinctures from previous decades were thrown out, and a Confederate surgeon formally introduced the idea that medical personnel should be treated as noncombatants.

Winchester, Virginia had been an operations base for the Union Army in the spring of 1862, and by May, well-furnished military hospitals received wounded from battles in the Shenandoah Valley. About seven hundred patients rested in the Union hospitals, and when General Banks and his blue-clad army made a dash for the Potomac River as the Confederates approached, seven surgeons elected to stay with their patients. Although intentionally killing wounded was a rarely reported occurrence during the Civil War, becoming a prisoner was a serious issue and could result in lengthy imprisonment in an unhealthy place until a parole could be arranged.

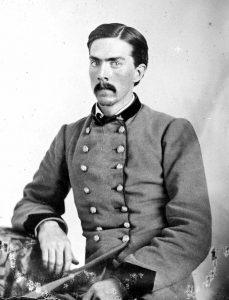

Alerted to the plight of the captured Union surgeons, Dr. Hunter McGuire discussed the situation with General Thomas J. Jackson and a surgeon from the Stonewall Brigade, Dr. Daniel S. Conrad. Hunter McGuire – just twenty-six at the time – had already gained a positive reputation for his surgical skill, innovative techniques, and willingness to reform or develop more effective battlefield medicine practices. (During the Valley Campaign, he had also been perfecting an ambulance corps to streamline evacuation from the battlefield, similar to Union Dr. Jonathan Letterman’s system.) Jackson trusted McGuire, and when the young medical director asked for a meeting, the others were willing to listen.

McGuire, Jackson, and Conrad decided to set a precedent, hoping the U.S. government and military would follow the example and ease the situation for captured surgeons on both sides. The document McGuire prepared seemed reasonable to the seven Union doctors and they quickly signed the agreement.

Winchester, Va. May 31, 1862

We surgeons and assistant surgeons, United States Army, now prisoners of war in this place do give our parole of honor on being unconditionally released to report in person, singly or collectively to the Secretary of War in Washington City as such and that we will use our best efforts that the same number of medical officers of the Confederate States Army now prisoners or may hereafter be taken be released on the same terms. And furthermore we will on our honor use our best efforts to have this principle established – the unconditional release of all medical officers taken prisoners of war hereafter.

(Signed)

J. Burd Peale, Brigade Surgeon, Blenker’s Div.

J.J. Johnson, Surgeon 27th Indiana Vols.

Francis Leland, Surgeon 2nd Massachusetts Vols.

Philip Adolphus, Assistant Surgeon, U.S.A.

Lincoln R. Stone, Assistant Surgeon 2nd Mass. Vols.

Josiah F. Day, Jr., Assistant Surgeon 10th Maine Vols.

Evelyn L. Bissell, Assistant Surgeon 5th Connecticut Vols.

Approved:

Hunter McGuire

Medical Director

Army of the Valley, C.S.[iv]

The agreement successfully introduced and pushed forward the idea with military commanders and the United States and Confederate governments that medical personnel should be treated as noncombatants and released as soon as possible to continue their life-saving work. The results were almost immediate. On June 6, 1862, U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton issued Special Orders No. 60 which “immediately and unconditionally” freed all Confederate doctors held prisoner. Robert E. Lee and George B. McClellan communicated officially, regarding the release of captured doctors in the Peninsula Campaign.[v] Although there were a few instances when the new idea collapsed, overall, this became the rule regarding prisoner doctors, assistants, and nurses throughout the remainder of the Civil War.

For Dr. Hunter McGuire, his own idea served him well in the final days of the conflict. Captured at the Battle of Waynesboro in March 1865 and taken to Union General Philip Sheridan’s headquarters, McGuire found that his reputation had preceded him. Sheridan treated him courteously and offered him immediate release and a two week parole, which the doctor accepted. He spent the two week parole in Staunton, Virginia – possibly visiting his sweetheart – and then rejoined the Confederate army just before the surrender and paroling at Appomattox Court House.[vi]

Following the Civil War, McGuire received credit for introducing the idea of classing medical personnel as noncombatants in America, though he followed in the footsteps of Swiss organizer of the Red Cross who had already started advocacy in Europe.[vii] The idea fostered by McGuire on American battlefields eventually became part of the Geneva Conventions and a foundational principle upheld by the American Red Cross and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Thanks to Dr. Hunter McGuire’s idea and the willingness of Drs. Peale, Johnson, Leland, Adolphus, Stone, Day, and Bissell to present the idea to authorities in the capital, the safety of medical personnel drastically improved. With the safety and quick release of doctors, assistants, and nurses ensured, care of the wounded progressed. It could be argued – considering the days when wounded were slaughtered as they lay helpless on the fighting fields – Dr. McGuire revolutionized American battlefield medicine by humanizing the battlefield and giving injured men a better chance to receive the care they needed to survive.

About the Author

Sarah Kay Bierle – author, speaker, and co-managing editor at Emerging Civil War – enjoys studying many aspects of the Civil War, especially the role of civilians, medical staff, and anything related to Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

Endnotes

[i] Robertson, James I. Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend. New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1997. Page 411.

[ii] Stephenson, Michael. The Last Full Measure: How Soldiers Die In Battle. New York: Broadway Paperbacks, 2012. Pages 43, 47.

[iii] Ibid., Page 121.

[iv] Shaw, Maurice F. Stonewall Jackson’s Surgeon: Hunter Holmes McGuire, A Biography. Lynchburg: H.E.Howard, Inc., 1993. Page 19

[v] Breeden, James O. “An Island of Hope in a Sea of Misery: Confederate Winchester and the Humane Treatment of Prisoners of War.” Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society Journal, Volume VII, 1993. Page 12.

[vi] Schildt, John W. Hunter McGuire: Doctor In Gray. Chewsville: Schildt, 1986. Page 94.

[vii] Ibid, Page 39

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.