Table of Contents

Almost 1,000 men served with the rank of general between both Union and Confederate armies throughout the Civil War. These men led troops on the front lines, made key decisions before, during, and after a battle, and were responsible for either victory or defeat. Needless to say, it is a pretty critical position and one that should be protected. 19% of Confederate generals died as a result of battle wounds and 49% were wounded. 8% of Union generals died of battle wounds, however we do not have an exact number of how many Union generals were wounded. [1] Let us take a look at some of the generals who received Civil War medical care.

This is Part 1 of our wounded generals’ series. Below are the stories of four generals wounded during the Battle of Gettysburg: Union Generals Daniel Sickles and Winfield Scott Hancock and Confederate Generals Lewis Armistead and William Barksdale.

Major General Daniel Sickles, III Corps, Army of the Potomac:

July 2, 1863, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The Union army held the ground from Little Round Top to Culp’s Hill with their lines resembling a fishhook. The orders given to General Daniel Sickles, commander of the III Corps by newly appointed General George Meade secured Little Round Top. However, Sickles advanced his corps into the Wheatfield and Peach Orchard, disobeying his orders, just as Longstreet was reaching the same area. A bloody fight ensued, and the fields changed hands multiple times over the next few hours before the III Corps was pushed back to Cemetery Ridge.

During the fight in the Peach Orchard, a Confederate artillery shell struck Sickles “while astride his horse, Sickles was struck in the lower right leg with a 12 lb. cannonball. The leg was amputated by Surgeon Thomas Sim that afternoon at the III Corps’ battlefield hospital.”[2] Initially he was thought to be dead by the men of the III Corps, however, according to an article in 1902, Sickles ordered the stretcher bearers to keep him on the field while shouting orders and smoking a cigar. This is highly unlikely as his leg suffered a very traumatic injury and he was bleeding profusely. What likely happened was Sickles gave a rallying farewell as he was being taken to the field hospital at the Daniel Sheaffer Farm on the Baltimore Pike.

After his leg was amputated, Sickles donated it to the Army Medical Museum, now the National Museum of Health and Medicine. He would famously often visit his leg in the museum and bring various guests to see it as well, though he was far from the only person with a limb on display to do so. Over thirty years after the Civil War, General Daniel Sickles received the Medal of Honor for his actions at Gettysburg on July 2 despite directly disobeying orders from his commanding officer. Sickles was also instrumental in the preservation and creation of what became Gettysburg National Military Park. He died in May 1914, just before the outbreak of World War I.[3]

Brigadier General Lewis Armistead, Armistead’s Brigade, Pickett’s Division, I Corps, Army of Northern Virginia:

General Lewis Armistead is one of the most well-known Confederate generals of the Civil War after his depictions in The Killer Angels novel and Gettysburg (1993 film). He was promoted to Brigadier General in 1862 and led his brigade through both Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. However, it was during the Battle of Gettysburg where he would be enshrined in Civil War memory. On the third day of battle, Generals Pickett, Pettigrew, and Trimble led their divisions to attack the Union center on Cemetery Ridge. Their objective was a stone wall also known as “the angle.”

To be more visible and easily identifiable by the men of his command, Lewis Armistead famously put his hat on the end of his sword and reportedly shouted “remember what you are fighting for – your homes, your friends, your sweethearts!”[4] His men marched a mile and a half, across an open field, straight at the Union center. Only a few hundred were able to make it over the stone wall, Armistead was one of them. Armistead had his hand on a Union cannon when he was shot and one by one, the men who went over the wall with him were either killed or captured as the attack failed.

Armistead was taken to the Spangler Farm for treatment. However, his wound was mortal, and Armistead knew it. In a last act, he gave some of his valuable and personal items to Union General Winfield Scott Hancock. The two had become friends after the Mexican American War and their final meeting was at Gettysburg on opposite sides. Two days later, Armistead died of his wounds, and he was buried in his family plot in the cemetery of St. Paul’s Church in Baltimore.

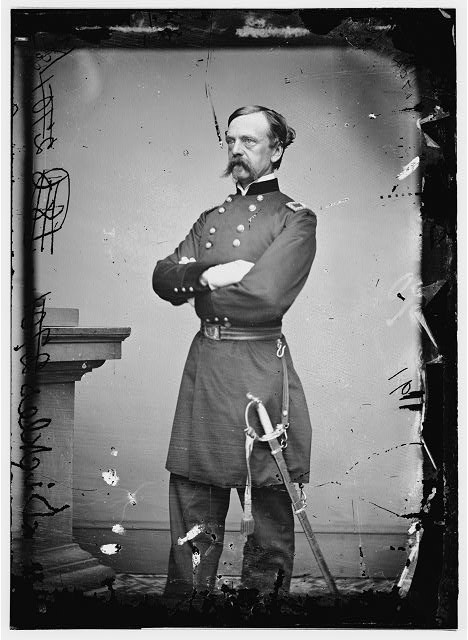

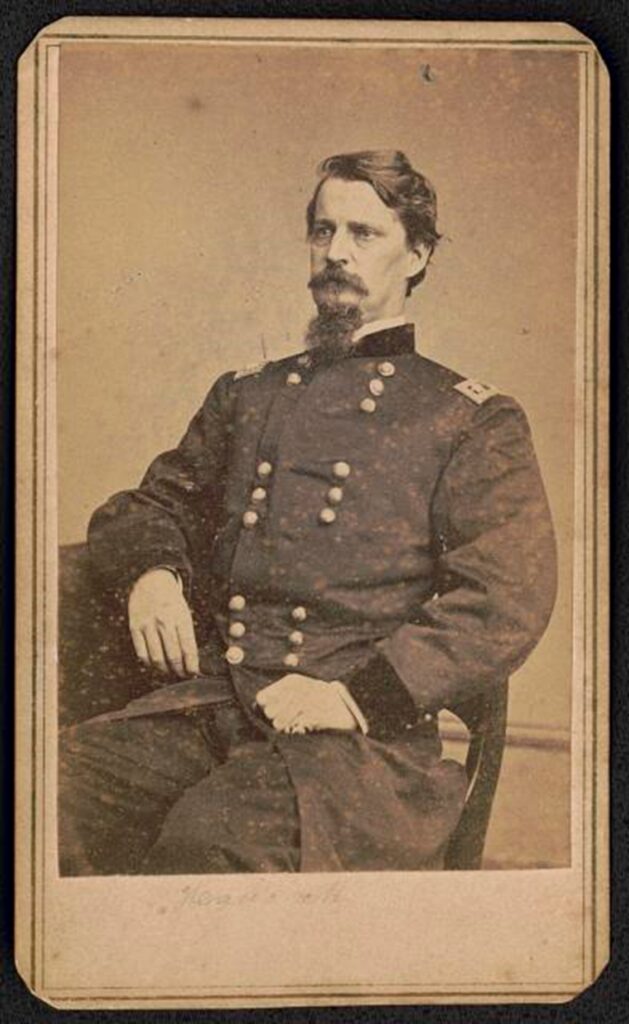

Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, II Corps, Army of the Potomac:

Major General Winfield Scott Hancock was recently promoted to corps commander before the Battle of Gettysburg and had temporary command of the “left wing” of the Army of the Potomac after General Reynolds was killed on the first day of fighting. Hancock was able to organize the retreating Army of the Potomac to concentrate around Cemetery Hill after losing ground north and west of Gettysburg. On the second day of battle, after Sickles unauthorized move, a substantial gap was created between the Union left and center. Hancock personally sent the 1st Minnesota to plug the gap and halt Confederate General A.P. Hill, a task which was completed at a great cost to the Minnesotans who suffered over 80% casualties, but they were able to save the Union lines from collapsing.

On the third and final day of the battle, Hancock’s corps made up the center of the Union line and was tasked with defending the stone wall known as “the angle.” During the fight, Hancock was wounded in the thigh. An account of Hancock’s wounding stated that “a ragged hole, an inch or more in diameter, from which the blood was pouring profusely, was disclosed in the upper part and on the right side of his thigh… the blood, being of dark color and coming in jets, could not be from an artery… We tightened the ligature by twisting it with the barrel of a pistol, and soon stopped the flow of blood.”[5]

The makeshift tourniquet used on General Hancock’s leg saved his life. While the wounded general was in a considerable amount of pain, he was able to keep both his life and leg and returned to command the following year. He remained in military service for the remainder of his life and took position as Commander of the Division of the Atlantic after the death of General George G. Meade in 1872. Hancock would go on to run against James Garfield for President in 1880. Major General Winfield Scott Hancock died several years later in 1886.

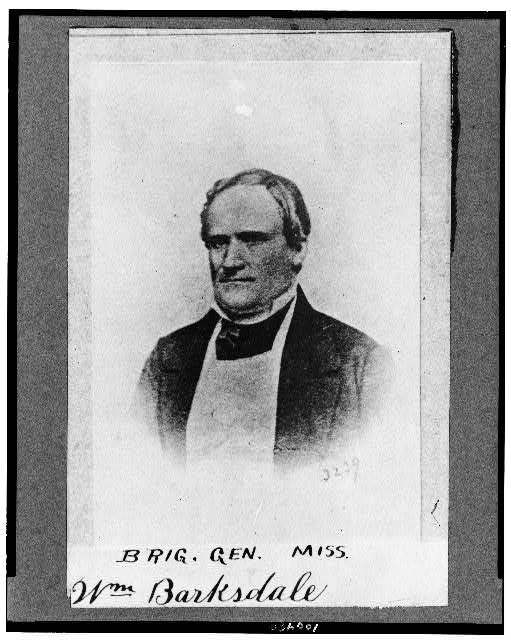

Brigadier General William Barksdale, Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade, McLaw’s Division, I Corps, Army of Northern Virginia:

William Barksdale was a US Congressman before the outbreak of the war, representing the State of Mississippi. Barksdale was one of the fire-eaters in Congress, a group of Southern politicians who actively sought secession. Barksdale allegedly stood beside Representative Preston Brooks as he nearly beat Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner to death. In 1861, Barksdale entered Confederate service as Colonel of the 13th Mississippi and commissioned as a Brigadier General over a year later.

Barksdale’s Mississippi brigade had previously distinguished themselves during the battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville before making their way to Gettysburg. On the second day of the battle, Barksdale was moving his brigade against Sickles’ III Corps at the Peach Orchard. During the fierce firefight between the two sides, Barksdale’s Mississippians were able to capture Union General Charles Graham. Around that time, while sitting on his horse, Barksdale was hit in the knee and left foot by artillery shells followed by a musket ball in the chest causing him to fall off his horse.

The men of his brigade were forced back and were not able to retrieve their wounded general. Barksdale was captured by Union forces and taken to the Joseph Hummelbaugh farmhouse. Brigadier General William Barksdale died the following day on July 3, 1863 as a result of his wounds.

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021.

Sources

[1] Saclarides, Theodore J. “Morbidity and Mortality of the Confederate Generals during the American Civil War.” U.S. National Library of Medicine, August 2007.

[2] Clark Jr., Tim. “Sickles’ Leg and the Army Medical Museum.” Military Medicine 179 (September 2014).

[3] Lange, Katie. “Medal of Honor Monday: Union Army Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles.” U.S. Department of Defense, July 18, 2022. https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/Story/Article/3093558/medal-of-honor-monday-union-army-maj-gen-daniel-sickles/.

[4] “Lewis Armistead.” American Battlefield Trust, n.d. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/lewis-armistead.

[5] Bierle, Sarah Kay. “General Hancock’s Tourniquet at Gettysburg.” Emerging Civil War, January 17, 2022. https://emergingcivilwar.com/2022/01/17/general-hancocks-tourniquet-at-gettysburg/#_edn1.