Table of Contents

This is part 2 of the Wounded Generals series. This article will examine the wounds of Union generals George Hartsuff and Robert Latimer McCook, and Confederate generals James Longstreet and William Brimage Bate.

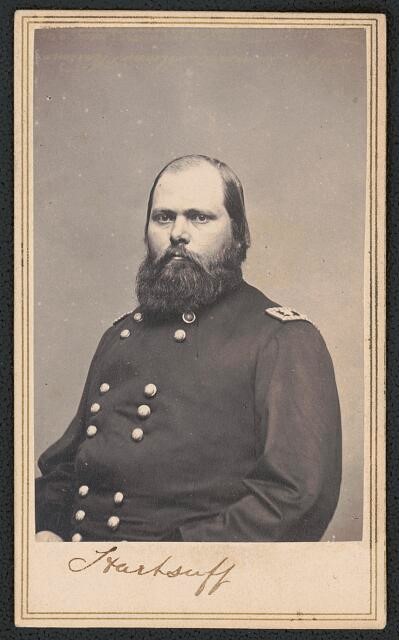

Brigadier General George L. Hartsuff, 3rd Brigade, Second Division, I Corps:

In the afternoon of the Battle of Antietam, General Joseph Hooker ordered his corps to advance from the North and East Woods. Orders were passed down to division and brigade commanders and the soldiers began to march. Instead of keeping in step with the 1st Brigade commanded by Brigadier General Abram Duryée, General Hartsuff stopped to rally his men. In the process of doing so, a Confederate sharpshooter shot him in the hip. The now wounded General Hartsuff finished sending out the men as he fell from his horse as a result of his wound. He was taken to the rear by stretcher to be treated for his wounds.[1]

Nearly every wounded Union soldier from the Battles of South Mountain and Antietam was eventually treated in one of 27 public buildings throughout Frederick, Maryland. General Hartsuff was taken to the home of Ms. Ellen Ramsey for his recovery. During his recovery, President Abraham Lincoln came to the Ramsey house after reviewing the Army of the Potomac.

General Hartsuff survived his wounds and was promoted to major general two months later. He took command of the XXIII Corps and was active until the end of the war, last seeing action during the Siege of Petersburg. He died in 1874 as the result of an infection from his wounds suffered in battle.[2]

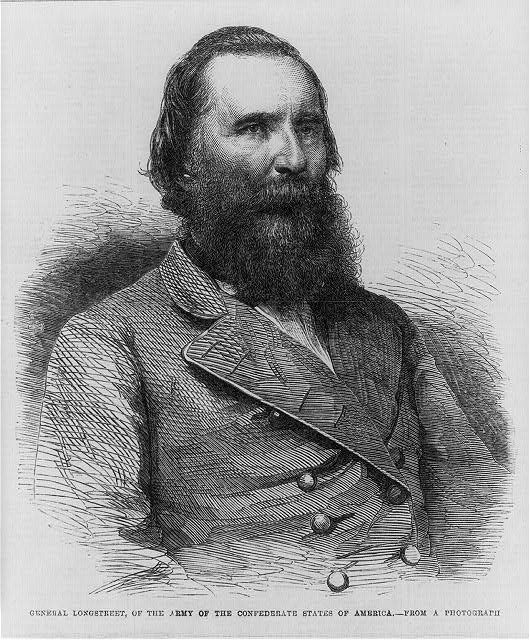

Lieutenant General James Longstreet, First Corps, Army of Northern Virginia:

Confederate General James Longstreet was regarded as one of the best Confederate generals of the Civil War. His prolific career as a general spanned the entirety of the Civil War. In 1864, Longstreet and his corps arrived just in time to repel a Union assault during the Battle of the Wilderness. After successfully leading an attack against Union lines, Longstreet and his staff were riding back to their headquarters taking a road that was supposed to be on the southern flank of General William Mahone’s Brigade. The 12th Virginia mistakenly crossed the road, and when the regiment realized the mistake, they attempted to return to their brigade on the other side of the Plank Road. The rest of the unit believed the 12th Virginia to be Union soldiers and fired several volleys into their own men.[3]

At the same time this was happening, Longstreet and his staff were traveling along this stretch of the Plank Road. In the ensuing chaos, Longstreet was struck by a miniè ball in the back right shoulder. The ball then traveled up and out through his neck and caused him to rapidly lose blood. Dr. John Syng Dorsey Cullen, medical director of Longstreet’s Corps, rushed to the fallen general and stabilized him before moving Longstreet to the field hospital. Dr. Cullen and several other surgeons concluded that the wound was not fatal, and Longstreet recovered and took command of his corps again later that fall.[4]

General Longstreet’s wound was eerily similar to the one suffered by General Thomas Johnson “Stonewall” Jackson one year and four days earlier. The wounds themselves were nearly the same; the bullet struck the same location and took the same path, the woundings occurred almost at the same month and day, and both were caused by friendly fire. The only difference was that Longstreet survived his wound and Jackson did not.

After the war, Longstreet moved to New Orleans and reignited his friendship with his former adversary, Ulysses S. Grant. During Grant’s presidency, Longstreet was appointed as minister to Turkey in 1880 and was later appointed as the commissioner of Pacific railroads under Presidents McKinley and Roosevelt from 1897 until his death in 1904.

Brigadier General Robert Latimer McCook, 3rd Brigade, First Division, Army of the Ohio:

Robert McCook was one of fourteen members of his family to serve in a combat role during the Civil War. Known today as the “Fighting McCook’s,” Robert entered the war as a colonel, and he was one of four McCook’s to hold the rank of general. Robert McCook took part in General D.C. Buell’s movements through Alabama, Tennessee, and Kentucky in 1862 where he became ill. While riding in the back of an ambulance wagon several miles in advance of the rest of his men, McCook’s party came upon a house near the Tennessee-Alabama border seeking information on where to set up camp.[5]

Out of the trees, a group of Confederate partisans and cavalrymen led by Frank Gurley attacked McCook’s carriage. In the ensuing chaos, the already sick and wounded McCook was shot while in the back of the ambulance, allegedly murdered by the Confederate attackers according to Northern reports. The remaining men took their mortally wounded general into a nearby house where he died 24 hours later.[6] There is some speculation over the exact circumstance of the death of General McCook. Robert McCook and his brother Brigadier General Daniel McCook Jr. did not live to see the end of the war.

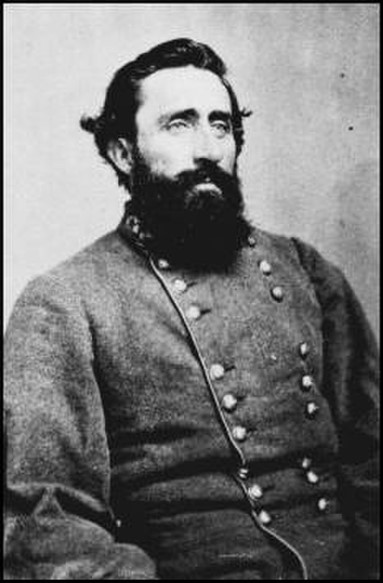

Major General William Brimage Bate, Bate’s Division, Hardee’s Corps, Army of the Tennessee:

Prior to Major General William B. Bate’s involvement in the Atlanta Campaign, he had been previously wounded at the Battle of Shiloh. The doctor told Bate that his leg was to be amputated as a result of the wound. In response, Bate drew his pistol, pointed it at the doctor, and urged him not to remove the leg. The surgeon obliged and Bate recovered with a limp that would last him throughout his life. After the Battle of Shiloh, he was asked to take the seat as Governor of Tennessee but declined in favor of military service[7]

Bate’s division was in the thick of the fighting during the Battle of Chickamauga and Bate had three horses shot out from under him.[8] He was also active during the Battle of Missionary Ridge and his actions at both battles earned him the rank of major general. When the Army of the Tennessee was being reallocated and reformatted, Bate was given his own division to command during the Atlanta Campaign.

During the Atlanta Campaign, he received his third and final wound during his military career. He was shot in the leg again (it is unclear if it was his previously wounded leg or the other one) and became confined to bed for several weeks to recover. He survived his wounds and began a law practice before entering the political sphere. He was elected as Governor of Tennessee in 1882, almost 20 years after he initially declined the offer. Four years later, he was elected to the US Senate where he served until his death in 1905.[9]

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021.

Sources

[1] Gottfried, Bradley, ed. Brigades of Antietam. Sharpsburg, MD: The Antietam Institute, 2021. 53

[2] Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue. La. State Univ. Pr., 1964. Pg 213

[3] Lively, Mathew W. “General Longstreet’s Wilderness Wound.” Civil War Profiles, July 14, 2014. https://www.civilwarprofiles.com/general-longstreets-wilderness-wound/.

[4] Lively, Mathew W. “General Longstreet’s Wilderness Wound.” Civil War Profiles, July 14, 2014. https://www.civilwarprofiles.com/general-longstreets-wilderness-wound/.

[5] “The ‘Fighting McCook’s.’” Daniel McCook Family, n.d. http://carrollcountyhistoricalsociety.com/McCook/Daniel/Daniel.htm#Robert_Latimer_McCook.

[6] Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue. La. State Univ. Pr., 1964. Pg 297

[7] Hill, Ray. “The Old Confederate: William Brimage Bate.” The Knoxville Focus, n.d. https://www.knoxfocus.com/archives/the-old-confederate-william-brimage-bate/.

[8] Hill, Ray. “The Old Confederate: William Brimage Bate.” The Knoxville Focus, n.d. https://www.knoxfocus.com/archives/the-old-confederate-william-brimage-bate/.

[9] Thweatt, John H. “Bate, William Brimage.” Tennessee Encyclopedia. Tennessee Historical Society, March 1, 2018. https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/william-brimage-baes/. \